I’ve just written a blogpost for the Cultural Capital Exchange – you can read it here.

I discuss the ethical issues posed in ethnographical research during the Covid-19 pandemic.

I’ve just written a blogpost for the Cultural Capital Exchange – you can read it here.

I discuss the ethical issues posed in ethnographical research during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Back in January, I started thinking about the repurposing of tunes by Georgian composers – whether arrangements, piano variations or other interpretations. Rossini particularly came to mind, because his operatic airs were so very heavily used – but it wasn’t just Rossini’s rights that intrigued me – what about all the other instances of repurposed tunes? I blogged, and then I threw the question open to the Claimed From Stationers’ Hall network, and – as I’ve already posted – Paul Cooper of RegencyDances.org and German folklorist Jürgen Kloss enthusiastically joined in the discussion, sharing some useful links to articles and postings that I’ve since incorporated into the 5th edition of our bibliography.

The conversation continued. Last week, Jürgen shared evidence that Scottish music publisher George Thomson became very concerned by the upstart Joseph Dale pirating piano music by Ignaz Pleyel that he, Thomson, had originally published. (I’ve used the Copac spelling of Pleyel’s forename here.)

German folklorist Jürgen’s thread was so intriguing that I offered to blog it in its entirety, and what follows is his input. I’d like to thank him for so graciously allowing me to reproduce his narrative on this blog.

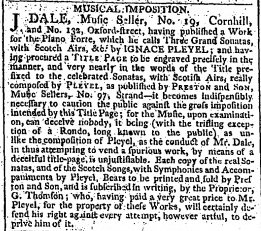

@juergenkloss (Jürgen Kloss) 12 Feb: Further to our early copyright discussions as to who “owns” the music?, I found this ad: “Musical Imposition”, in which George Thomson – editor and publisher of Scottish songs – warns against a “spurious” ed. of sonatas by Pleyel, publ. by J. Dale:-

Indeed, Thomson regarded Dale’s ed. (ad in OAPA, 12.3.1794) as an attack on his own investment: “G. Thomson, who, having paid a very great price to Mr. Pleyel, for the property of these Works, will certainly defend his right against every attempt, however artful, to deprive him of it.”

Of course Mr. Dale kept on publishing these works: Twelve Grand Sonatas for the Piano Forte or Harpsichord […] In Which are Introduced a Variety of Scotch Airs, Book 2 (1798) (this copy in the University of Iowa Digital Library):- http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/pleyel/id/8775 … And he claimed to have the original editions:-

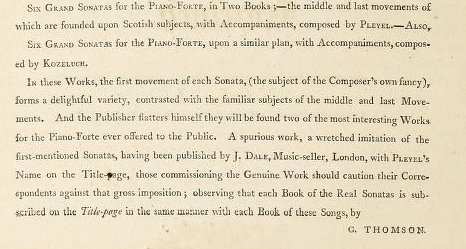

Even several years later, in some editions of his Select Collection, Mr. Thomson still warned against the “wretched imitation” published by Dale.

https://archive.org/details/selectcollection00pley/page/n9 …

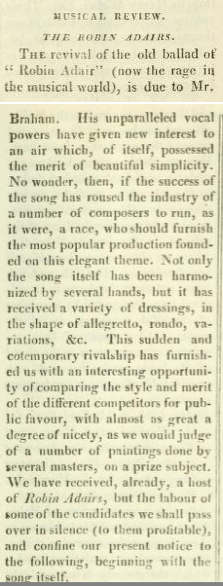

And here’s another disputed instance: that of “Robin Adair”. (See Jurgen’s blog of 2014, link below.) This old tune was revived in 1811. Composer William Reeve wrote a new arrangement and John Braham sang it with a new text. The new “Robin Adair” was a great hit… https://hummingadifferenttune.blogspot.com/2014/02/john-brahams-robin-adair-1811-original.html …

And here’s another disputed instance: that of “Robin Adair”. (See Jurgen’s blog of 2014, link below.) This old tune was revived in 1811. Composer William Reeve wrote a new arrangement and John Braham sang it with a new text. The new “Robin Adair” was a great hit… https://hummingadifferenttune.blogspot.com/2014/02/john-brahams-robin-adair-1811-original.html …

…and of course other publishers quickly offered their own editions. But Mr. Reeve sent letters to newspapers warning against “spurious” editions. This letter even appeared on the title-page of the sheet music, see below: https://archive.org/details/sheet-music-RobinAdair-Braham-London1812 …

Interestingly, composer J. Mazzinghi couldn’t resist publishing an answer to Mr. Reeve’s claims in his own edition of “Robin Adair”. He said it was a big success because of the tune and Braham’s performance (and Reeve had no rights to the song)! http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/fa-spnc/id/8566 …

Of course: songs are money, especially popular hits like this one. Later it was claimed that “in one year, […] upwards of two hundred thousands copies” of the sheet music were sold. Therefore it is understandable that Reeve was a little bit nervous about competing editions:-

There is much fascinating detail to absorb in these stories that Jürgen has generously shared with us.

MAYBE YOU’D LIKE TO LEARN KNOW MORE?

Jürgen’s newspaper references are available via these electronic resources:-

Jürgen also traced a reference to a paper that Claire Nelson gave at the International Musicological Society’s 17th Congress in Leuven, in 2002. Here’s the abstract:-

Jürgen also traced a reference to a paper that Claire Nelson gave at the International Musicological Society’s 17th Congress in Leuven, in 2002. Here’s the abstract:-

The paper wasn’t published in its entirety that year – just the abstract, in the conference programme above – but the good news is that it became a chapter in Nelson’s doctoral thesis in 2003, when she completed her DMus at the Royal College of Music. The thesis can now be downloaded free of charge via the British Library’s EThOS service.

Nelson, Claire M., Creating a notion of ‘Britishness’ : the role of Scottish music in the negotiation of a common culture, with particular reference to the 18th century accompanied sonata (Royal College of Music, 2003, Access from EThOS:- https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.489910

Go to page 240 of Nelson’s thesis to read more about George Thomson’s disgust at Joseph Dale’s shameful piracy. She quotes (and provides an English translation) from a letter that Thomson wrote to Pleyel in 1794:-

“Dale has done something most shameful and most offensive. He has published three sonatas with Scottish airs, exactly on the same plan as mine, and their title is engraved in the same way and almost in the same words, your name is given as the composer! His intention is evidently to deceive the public and without regard to my sonatas, pass a work supposedly of your composition, I have published an advert revealing the fraud, and hope that you have had no part in the work of Dale.”

Thesis footnote 102, translating the French original reproduced in Pincherle’s 1928 article, (Marc Pincherle, ‘L’Edition Musicale au dix-huitieme siecle: Une letter de Thomson a Ignace Pleyel’, Musique i (1928), pp.493-498), p.496.

Of particular interest in this context are the articles by William Lockhart ( ‘Trial by Ear: Legal Attitudes to Keyboard Arrangement in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, Music & Letters, 93.2 (May) (2011), 191–221 https://www.jstor.org/stable/41684166 [accessed 31 January 2018]) and Charles Michael Carroll (‘Musical Borrowing: Grand Larceny or Great Art?’, College Music Symposium, 18.1 (1978), 11–18 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40373912 [accessed 12 January 2019]) – but seriously, there is a lot more to read if you’re keen to find out more! And of course, don’t forget that Jürgen Kloss and Paul Cooper have both written extensively on the subject – their blogposts are also listed in the bibliography, naturally.

(I must confess that I’m eager to download Pleyel’s Twelve Grand Sonatas – whatever the edition! – to see what they’re like, too!)

I authored the following piece for the UK Copyright Literacy website. New readers are warmly encouraged to explore our Claimed From Stationers’ Hall blog, and please do sign up to the Jisc mail list if you would like to join the conversation.

Legal Deposit (Copyright Behind the Scenes) – and Scores of Musical Scores

It is with great pleasure that we share our second guest blogpost, this time by Dr Kelsey Jackson Williams, Lecturer in Early Modern Literature at the University of Stirling, and Printer, The Pathfoot Press. If you’ve ever wondered what the process of music engraving actually entails, then your questions are about to be answered here.

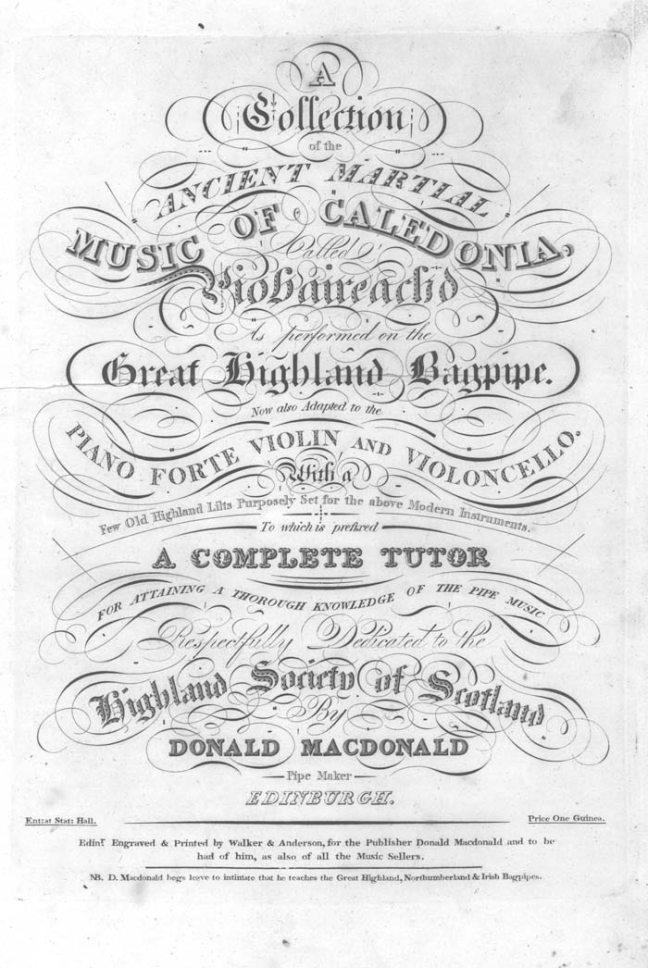

One of the vast treasure trove of musical scores which falls within the remit of the Claimed from Stationers’ Hall project is the imposingly named A Collection of the Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia, called Piobaireachd as performed on the Great Highland Bagpipe. Now also adapted to the Piano Forte Violin and Violoncello. With a few old Highland lilts purposely set for the above modern instruments. To which is prefixed a complete tutor for attaining a thorough knowledge of the pipe music, compiled by the Skye native and prominent bagpipe-maker Dòmhnall MacDhòmhnaill (1766/7-1840) and published in Edinburgh in 1820.

Like many musical scores of the period, MacDhòmhnaill’s work was reproduced through copperplate engraving, a process which remained a mainstay of music publishing until the dawn of the twenty-first century (I was surprised to discover in the process of my research for this blogpost that even the Henle Verlag scores I practiced from as a teenager were still made by this traditional process!). Copperplate engraving, as the names implies, involves the etching of the image, in this case a score, on a copper plate with a stylus known as a burin. For musical publishing, it offered what could often prove to be a more economical, cleaner method of producing a score than the setting of music in moveable type, a slow, expensive, and painful process at the best of times.

But copperplate engraving was also a highly specialised skill, only invented in the fifteenth century and slow to spread across Europe. As late as 1732 Alexander Munro’s Collection of the Best Scots Tunes escaped the net of the 1709 Copyright Act because it was printed not in Edinburgh, as might have been expected, but in Paris, quite probably because the engravers of Edinburgh were not yet up to the task of preparing forty-five pages of music for the press.

How, then, did Edinburgh music publishing make the leap from the Parisian workshop of Jacques Dumont in the 1730s to the Edinburgh offices of Walker and Anderson in the 1820s? Many aspects of that story remain, as yet, unknown and I don’t propose to answer this question here, but rather to digress somewhat – in typical academic fashion – and look at the origins of the Scottish engraving industry, the same which would eventually produce craftsmen able to create such polished and elegant pieces as MacDhòmhnaill’s Piobareachd.

That industry had its origins in the Scottish early Enlightenment. Only a handful of engravers were active in Scotland in the latter part of the seventeenth century, though some of those produced work of a very high standard. Beginning around 1700, however, the Scottish engraving market began to expanded exponentially with somewhere in the region of fifteen to twenty engravers being active in Edinburgh alone during the first quarter of the century. It was no coincidence that this coincided with a shift in the Scottish printing economy. Beginning with the 1707 publication of volume one of George Mackenzie’s Lives and Characters of the Most Eminent Writers of the Scots Nation, Scottish printers and booksellers turned to a subscription model for producing specialist, high-cost works, whether those were antiquarian, literary, or musical in their contents. By shifting the economic risk from the printer to the individual subscribers, the Scottish book trade was suddenly able to produce far more of these works than it had before and this, in turn, led to the creation of a niche but growing market for print luxuries like engraving.

While Munro’s Collection fits within this narrative – boasting as it does an impressive subscription list of the great and the good of early eighteenth-century Scottish society – it was by no means the first time that engravers had been co-opted into the subscription publication model. Instead, this had previously happened with works on antiquarianism, particularly heraldry. Scholars such as Alexander Nisbet (1657-1725) had come close to bankrupting themselves commissioning lavish engravings for their works, engravings which offer some of our best evidence for the extent and skill of the trade at the time.

It was no surprise that Edinburgh engravers were more comfortable with heraldry than with music. Some of our earliest evidence for Scottish engraving comes in the form of heraldic bookplates and it seems likely that the first growth of the trade in Edinburgh was in response to the growing fashion for bookplates amongst the middle- and upper-class reading public of Enlightenment Scotland. As private libraries grew apace, their owners looked to the urban luxury trades – whether engravers, book binders, or others – for ways to distinguish theirs from the mix.

What the ultimate origins of Scottish engraving were – whether lying with Scots training on the continent or continental engravers immigrating to Scotland – and how it first developed its musical side are areas which remain to be studied. I’ll happily leave the latter to other, more knowledgeable scholars than myself, but I’m currently working on the former as part of a larger project on the arts and thought of early Enlightenment Scotland (which you can read more about here). I’ll sign off for the moment, though, with the reflection that, odd as it may seem, the origins of Scottish musical engraving lie in the production of bookplates for aristocratic readers in the intellectually teaming environment of Edinburgh at the turn of the eighteenth century.

Kelsey Jackson Williams

University of Stirling