This has become a two-post day? Well, it’s International Women’s Day. How can I not mention it?

I decided I would play music by women this morning. Rose Smith (one of the women I recently wrote about in the RMA Research Chronicle – you’ll be familiar with her name by now!) was a piano teacher, a composer, and an Episcopalian organist. She was born in Lanark, moved to Glasgow whilst still a child, and later lived with her husband and children in Rutherglen. Her composed songs were rather like those by Ivor Novello – I’ve acquired nearly all of what seems to be extant, but I think a lot is missing. She only self-published a few, and the rest – for variety show singers – may not even have been published at all.

There’s no surviving organ music, so there was nothing for it – I played her songs before morning worship today. I bet you she never played them in church! However, since no-one knew they were secular songs, there was no harm in it. They’re well-written pieces, and I do think it’s a shame they’re not known. I did recommend one to an RCS Finalist a few years ago, and it was performed with enjoyment and appreciation.

I have significant performance anxiety about recording my playing, but I did unearth a piano demo of three songs by Rose Smith, that I recorded for a student a few years ago. Be kind! This isn’t a perfect performance or a perfect recording, but does show how the songs go.

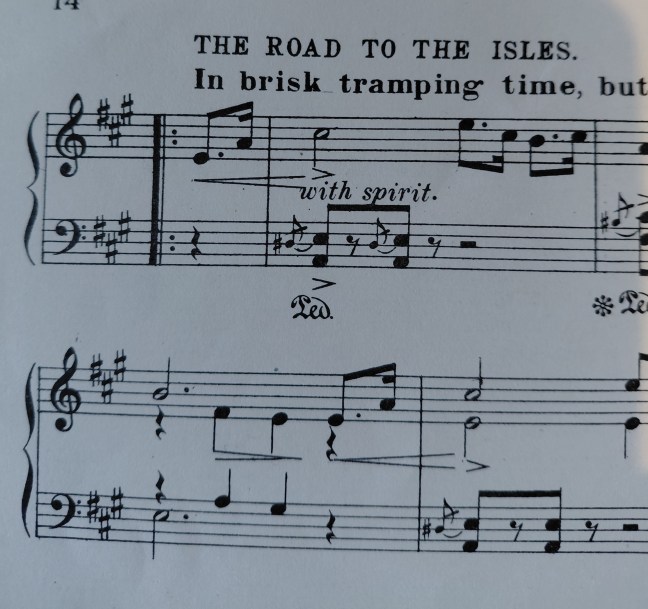

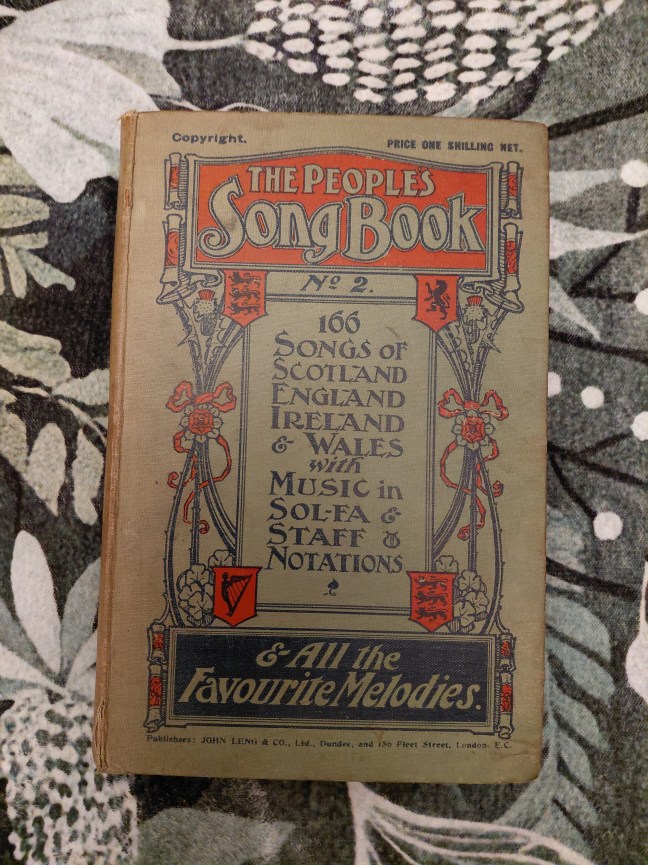

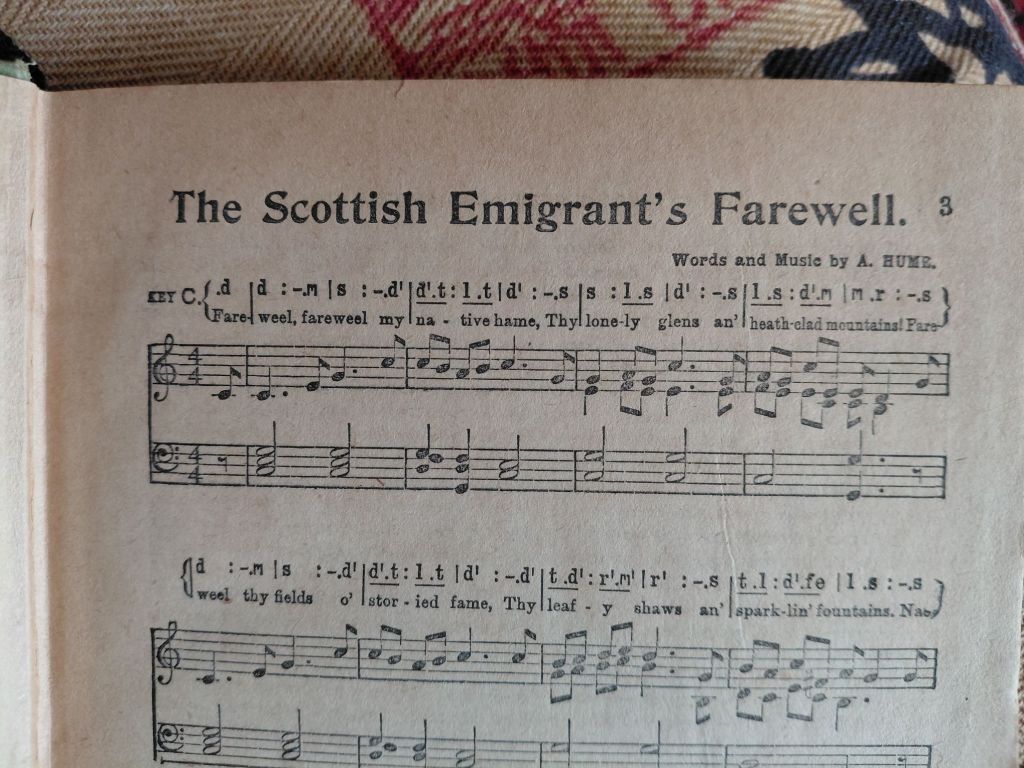

For my outgoing voluntary today, I turned to a more well-known composer. I played Marjory Kennedy-Fraser’s Eriskay Love Song, followed by The Road to the Isles.

Applause

I scored! I don’t usually get a round of applause after a voluntary.

I’ve got a new book of proper organ voluntaries by women composers, so I really must roll up my sleeves and learn some of them, but I suspect The Road to the Isles will prove hard to beat, as far as audience reaction goes …