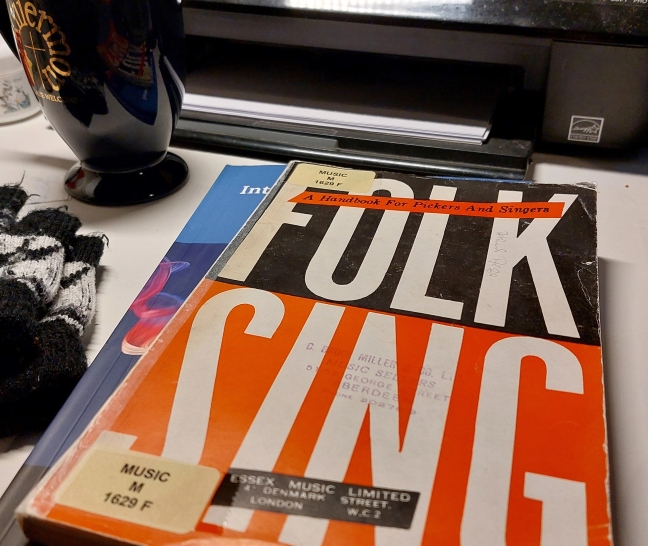

In the closing pages of my second monograph (currently at the publishers, pending approval of the revisions and then copy-editing), I comment on the changing approaches to folk music in the late 1950s and 60s. So, when a colleague presented me with a pile of music which used to be in the library, but needed recataloguing (don’t ask!), my immediate reaction to this book was, ‘Aha, see, I was right. Look how different this is to Mozart Allan, James Kerr’s and Bayley & Ferguson’s folk song collections!’

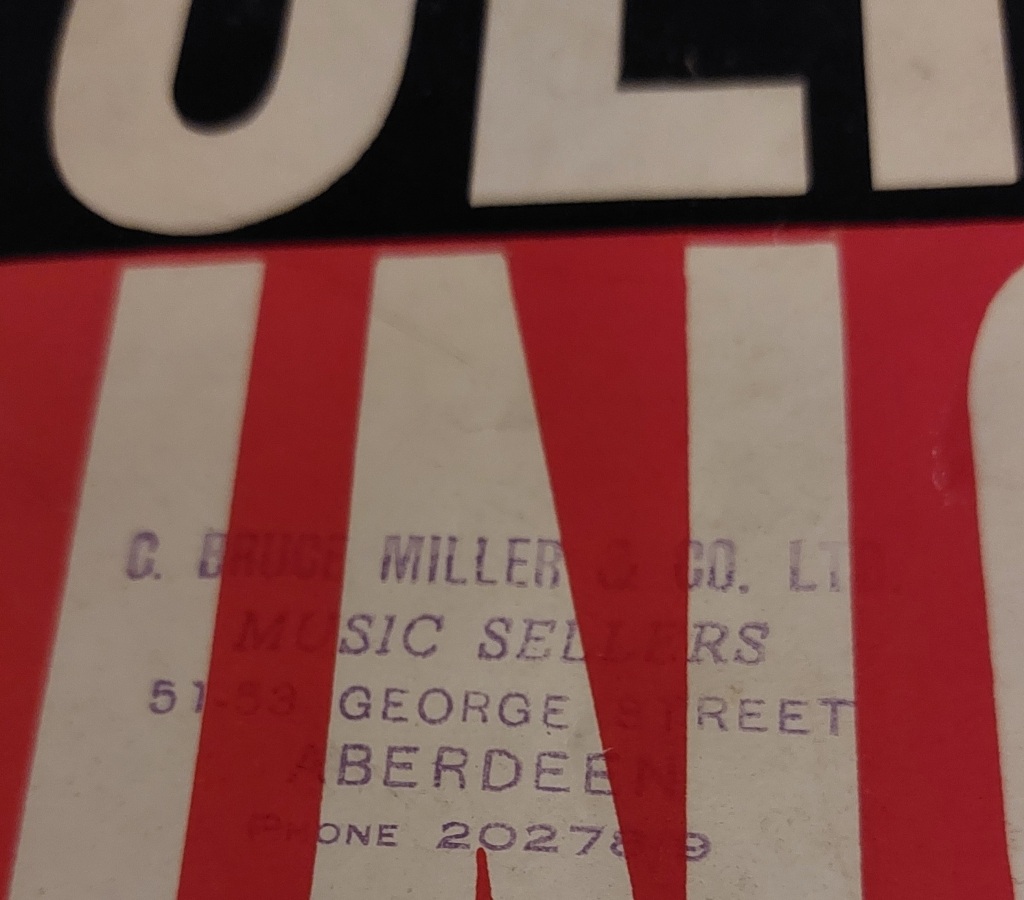

As a scholar, I smiled with satisfaction as I noted that even the COVER of Folk Sing: A Handbook for Pickers and Singers was more modern – huge white letters on a half-black, half-red background. As for ‘pickers and singers’: well, we didn’t have ‘pickers’ in any of the dozens of Scottish publications that I’ve been writing about! Guitar/accordion chords as an addition, assuredly, but not usually melody, chords and no keyboard line. And as for the term, ‘pickers’? No. A more savvy friend informs me that the book came at the end of the skiffle revival, which according to Oxford Music Online was particularly strong in the UK:-

“While the skiffle revival of the 1950s embraced the USA and Germany, it gained most ground in Great Britain. […] Donegan and his imitators enjoyed considerable popularity until about 1959, when skiffle gave way, both in the USA and Europe, to ‘beat’ music and to rock and roll.”

Oxford Music Online (2001). Skiffle. Grove Music Online. Retrieved 19 Jan. 2024, from https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000025930.

This song book was published in New York by Hollis Music in 1959, but distributed by Essex Music (4 Denmark Street) in London, and this particular copy was actually sold from a shop in Aberdeen. Notwithstanding this, it mainly contains American repertoire with just a few British songs and a single French one for good measure.

I examined it inside-out and backwards, observing contentedly that they indicated the names of the composer/arranger/lyricist above each song, along with which publishers owned the original copyright.

Then I sighed. This morning I had noted with pleasure that already this month, I’ve submitted a revised manuscript for my book, written a librarianship-ish article and two musicology abstracts, done a peer-review and a radio interview, with a research talk coming up to round off the month. That was my research-self.

But what I was supposed to be doing now, was cataloguing this anthology, not studying it.

‘Recataloguing’ means that I have already catalogued the book at some stage in the past … yawn!

The librarian part of me spent half this afternoon re-cataloguing it and copy-typing 150+ song titles from the contents list. It’s certainly useful – it means people will be able to find the songs – but it’s not nearly as rewarding!

Folk Sing: a Handbook for Pickers and Singers, containing traditional and contemporary folk songs / edited by Herbert Haufrecht (New York: Hollis Music; London: Essex Music, 1959)

Do note and admire the contents lists!