Hans Gal (1890-1987) catalogued Edinburgh University’s Reid Music Library during the summer and autumn of 1938, at the instigation of Sir Donald Tovey. The latter was keen to find work for the gifted composer and musicologist, who had emigrated from Vienna when Hitler annexed Austria. (Here’s a recording of his earlier Promenadenmusik for wind band, which he wrote in 1926. ) A grant from the Carnegie Trust enabled Gal’s catalogue to be published in 1941. When the Second World War ended, Gal joined the University music staff, and remained there beyond retirement age.

The reader is referred to the Hans Gal website for further biographical information (I am checking this weblink, which occasionally falters):- http://www.hansgal.org/

Gál, Hans, Catalogue of manuscripts, printed music and books on music up to 1850 : in the Library of the Music Department at the University of Edinburgh (Reid Library) (London, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1941)

The catalogue is in three parts, listing manuscripts, printed music, and books on music. Gal did not list every individual piece of music in the library, but prioritised more serious classical music, whether vocal or instrumental. One might suggest that there were various reasons for Gal’s decision.

In his preface, he explains that, ‘for practical reasons I confined this catalogue to the old part of the library, namely the manuscripts, printed music and books on music up to 1850, which is the latest limit of issues that might be looked upon as of historical importance’. [Gal, vii]

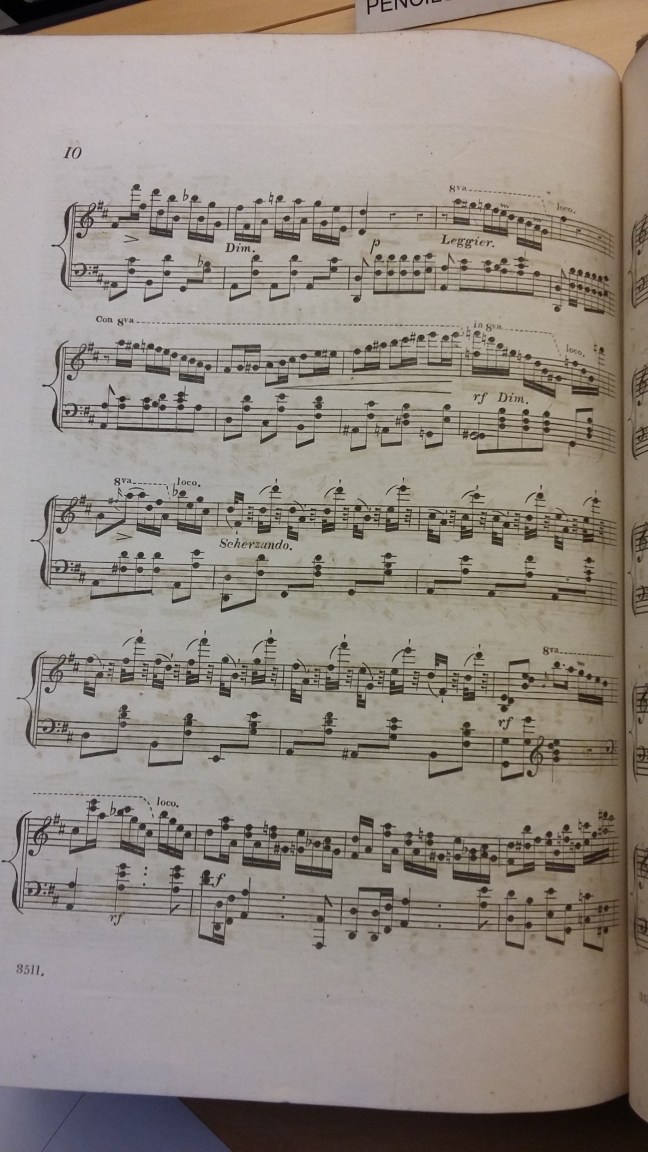

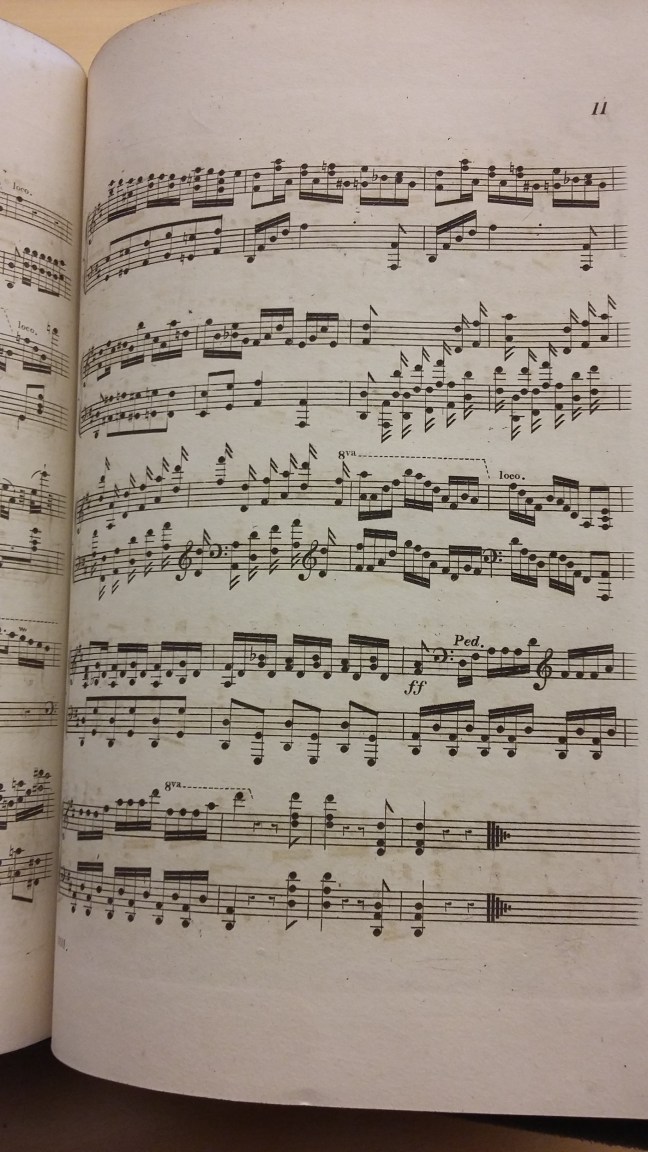

However, this was not the only limitation placed on the listing. Gal omitted many of the pieces of sheet music that must have arrived as legal deposit copies during the Georgian era, until copyright legislation changed in 1836. The Reid music cupboards contained a number of Sammelbänder, or ‘binder’s volumes’, ie, bound volumes of assorted pieces of music. Occasionally Gal made oblique reference to these, eg, to cover the 44 items in volume D 96:-

“Songs, Arias, etc., by various composers (Th. Smith, D. Corri, Bland, R. A. Smith, Rauzzini, Davy, Kelly, Urbani; partly anon.) Single Editions by Longman & Broderip, Urbani, Polyhymnian Comp., etc., London (ca. 1780-1790). Fol. D 96″ [Gal, 44]

Longman & Broderip were prolific music publishers, amongst the most assiduous of firms making trips to Stationers’ Hall to register new works. They published a lot of theatrical songs and arrangements, and much dance music, as well as the more serious, ‘classical’ music repertoire. The catalogue entry cited above details some more commonly known composers of decidedly middle-of-the road, if not downmarket material. One does not need to speculate as to whether Gal considered such material less respectable, for he made no secret of his disdain for much of the music published in this era! In the preface, he asserts that,

“The gradual declining from Thomas Arne to Samuel Arnold, Charles Dibdin, William Shield, John Davy, Michael Kelly, is unmistakeable, although there is still plenty of humour and tunefulness in musical comedies such as Dr Arnold’s “Gretna Green”, Dibdin’s “The Padlock”, Shield’s numerous comic operas and pasticcios.

“After 1800 the degeneration was definitive, in the sacred music as well as in songs and musical comedy. […] It is hardly disputable that the first third of the nineteenth century, the time of the Napoleonic Wars and after, was an age of the worst general taste in music ever recorded in history, in spite of the great geniuses with which we are accustomed to identify that period.” [Gal, x]

Faced with several hundred of such pieces in a number of bound volumes, and quite possibly a limited number of months in which to complete the initial cataloguing, it is hardly surprising if Gal was content to make a few generic entries hinting at this proliferation of ‘bad taste’. (One might add as an aside, that Gal’s wife at one point observed that Gal ‘hated swallowing the dust in archives’, in connection with an earlier extended project in the late 1920s – clearly, he was able to overcome his distaste when the need arose! (See http://www.hansgal.org/hansgal/42, citing private correspondence of 10.10.1989)

Interestingly, it is evident that Edinburgh, like several other of the legal deposit libraries, must have been selective in what was retained, but it’s significant that national song books were certainly considered worth keeping. Gal, in turn, included some of the prominent titles in his listing.

Thus, Gal’s catalogue is another reminder to us that the history of music claimed from Stationers’ Hall under legal deposit in the Georgian era, actually and actively continues beyond the Georgian era, for the material has already been curated by musicologists and bibliographers prior to our own generation. In St Andrews, Cedric Thorpe Davie took an active interest, whilst Henry George Farmer was involved in curating the University of Glasgow collection.

Meanwhile, in connection with the current Claimed From Stationers’ Hall network research, the priority is to establish which volumes – formerly in the Reid School of Music cupboards, but now in the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections – were received under legal deposit. Two spread-sheet listings enable us to examine the contents of different volumes, by volume:-

Centre for Research Collections: Directory of Rare Book Collections: Reid Music Library:- https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/library-museum-gallery/crc/collections/rare-books-manuscripts/rare-books-directory-section/reid-music

Where publication dates are not given in the spread-sheet, they can be looked up in Copac, and even if there are no decisive dates, then their presence in other legal deposit collections will suggest that these copies arrived by the same route. If music predates 1818, then works can be looked up in Michael Kassler’s Music Entries at Stationers’ Hall, 1710-1818, from Lists prepared for William Hawes, D. W. Krummel and Alan Tyson. (Click here for Copac entry.)

Essentially, the first task is to ascertain which volumes contain legal deposit music, and then to look not only at what survives, but whether there are any patterns to be discerned. In terms of musicological, book, library or cultural history, the question today is not whether the music was ‘degenerate’ or in ‘bad taste’, but to ask ourselves what it tells us about music reception and curation in its own and subsequent eras.

I’d better get back to the spreadsheets!

Here’s a piece Gal wrote in 1939, only a short while after his cataloguing months:

Postscript: as an interesting twist in the world of library and book history, my own copy of Gal’s catalogue was purchased secondhand – a withdrawn copy from a university library where the music department closed a few years ago. What goes around, comes around, as they say!