This is an article that I wrote whilst on vacation at the New Year, for the Glasgow Society of Organists’ newsletter, The Glasgow Diapason. I’m reproducing it here, because it may become hard to find copies of a newsletter with a comparatively small circulation, in years to come. I’ve added some information to Table 2, indicated as Addenda, and I’ve added two scans from The National Choir Vol.1.

The image above is (was) St George’s Church in Paisley – it has now been converted into flats.

The citation details of my article are as follows:-

Karen E McAulay, ‘‘Our Heroine is Dead’: Miss Margaret Wallace Thomson, Paisley Organist (1853-1896)’, The Glasgow Diapason, March 2023, 10-15.

I’m currently writing a book about Scottish music publishers and amateur music-making. Thinking to do a little light research over Christmas, I borrowed J & R Parlane’s The National Choir, a collection of part-songs published first in separate numbers from 1887, and subsequently in two volumes by ca. 1895. This Paisley firm was a significant producer of all kinds of books, including educational music in staff and Tonic Sol-Fa notation. The collection met the need for straightforward choral material for a growing number of amateur choirs; with over 100 contributors, it bore out the editor’s boast that it afforded opportunities for many local professionals and amateur composers and arrangers to make contributions. Containing predominantly Scottish song settings, the second volume also set out to broaden the scope a little further by including national songs from elsewhere in Britain, amongst other items.

Let us now praise famous men … (Ecclesiasticus XLIV)

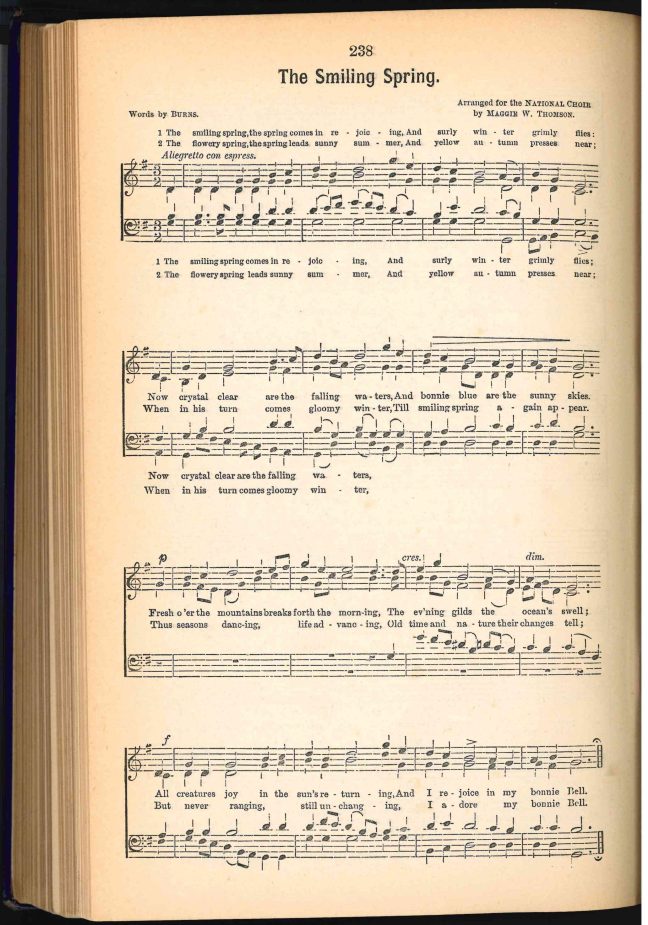

Only a musicologist would sit down and tabulate every single contributor in 768 pages of music, and only a musicologist with an interest in women composers would count the number of female contributors. Margaret Wallace Thomson of Paisley was one of only two women represented, with an arrangement of Burns’s ‘The smiling spring’ and a song of her own, ‘The weary day’. (The other lady was Mrs R. Broom, a songwriter who had contributed the melody for one song, ‘Over the sea’.) Both ladies appeared in the first volume, the prefatory notes informing us that Miss Thomson was a Paisley pianist and organist, whilst Mrs Broom had written several popular songs. The latter remained an enigma, but there were numerous mentions of Miss Margaret (or Maggie) Thomson in the local press; she had a good reputation as an organist, piano accompanist and music teacher. Indeed, accompanying the Paisley Choral Union for some two decades, she received a gift of a gold watch and chain after her first three years with them, and generous tributes upon her untimely death at the age of 42.

I was particularly curious about her, since I was once a Paisley organist myself. Once I started looking, I found out more and more – another musical woman who had been forgotten through time, her lack of publications probably partly to blame.

Margaret’s father Alexander was an Irishman, who had seemingly come to Scotland before he met Susan Wallace, a Paisley girl. They both worked in the weaving trade as pattern setters. Susan still did this in 1851, when they had started their family, but seems not to have been doing it by 1861. Later, Alexander was a flower lasher, carrying out an intricate weaving process for Paisley shawls. Three sons and a daughter came along before Margaret’s birth, although her nearest brother died when she was only three. Alexander, the firstborn, became a manufacturer by trade; a violinist, he conducted the Paisley Musical Association orchestra in his spare time. Her sister Isobella became a qualified teacher, and was the first woman teacher at Paisley Grammar School before she left to marry. Margaret herself would attend that school. They had a younger brother, James Paterson Thomson, who also became an organist, violinist and music teacher.

By the time she was 20, in 1873, Margaret was advertising her services as a music teacher, working from home. She continued to advertise as a music teacher until 1895, the year before she died. Appointed organist at St George’s Parish Church in Paisley in 1876, she had already acquired experience at Paisley’s Trinity Episcopal Church. James was organist at North Church from 1884. Margaret’s adverts always identified her as ‘organist of St George’s’, but James’s1895 teaching advert did not allude to his being an organist that year. When he died of alcoholic poisoning in 1897, the records say that he was a violinist; maybe he had stopped playing in church.

The many press notices of Margaret’s appearances bear witness to a number of regular activities. In her capacity as organist, she gave annual concerts with St George’s choir. As accompanist to the Paisley Choral Union, she accompanied a number of the Saturday Afternoon Concert series taking place in the George A. Clark Town Hall. She was also involved with the massive annual summer outdoor concerts commemorating Tannahill at “The Glen” on the Gleniffer Braes, contributing arrangements of Scottish songs for choir and band, for performance under the direction of Mr J. Roy Fraser, a Paisley music-seller. Proceeds were being saved towards a statue for Robert Burns’s impending centenary in 1896. (As an indication both of the popularity of these concerts, and the enthusiasm for choral singing, it is worth noting that on a rainy summer’s day in 1889, it was regretted that the audience was uncharacteristically probably under 10,000, and that the choir sadly numbered under 200 singers!)

She provided music for other entertainments and talks; including accompanying children in music exams; accompanying the Wallneuk Mission Choir; and, ironically, participating in a concert for inmates at Riccartsbar Asylum, where she herself would later die. She seems to have played piano, harmonium or organ depending on the engagement, but is never recorded as having conducted a choir; this was probably considered unseemly for a genteel woman of the time.

The choral repertoire that she was accompanying was is a mixture of established ‘greats’ still performed today, and other works now long forgotten:-

| William Bradbury (1816-1868) | Esther: cantata |

| Alfred R Gaul (1837-1913) | Ruth: cantata |

| Gounod | Jesus, Word of God |

| Handel – | Judas Maccabaeus: oratorio (excerpts) |

| Handel | The Messiah |

| Handel | Samson (excerpt) |

| Haydn | Creation |

| Henry Lahee (1826-1912) | The building of the ship: cantata |

| Mendelssohn | Elijah: oratorio (excerpts) |

| Mendelssohn | St Paul (excerpts) |

| Mozart | 12th Mass (excerpts) |

| John Owen (1821-1883) | Jeremiah: oratorio |

| T Mee Pattison (1845–1936) | The Mother of Jesus: cantata |

| Scotch Selections | (piano contribution) |

| Sullivan | Oh, love the Lord |

| Sutcliffe | The voice of Jesus |

Table 1: Repertoire

Such as found out musical tunes

Maggie probably falls into the category of amateur contributors to The National Choir. Her musical arrangements and occasional compositions are very slight. She provided an arrangement of a Burns song, and one original piece; each occupy only one side, and are competent, but not outstandingly original. The titles of a few more of her Scottish song settings can be gleaned from press reports of the Tannahill concerts, and the only other extant musical item is a setting of Tennyson’s ‘Break, break, break!’, which was a collaboration with Alexander Wallace Waterston – another Paisley musician, who could conceivably have been a relative. Her own song, ‘The voice of the deep’, remains untraced.

| Break, break, break!, by Wallace Waterston, piano accompt by MWT (1894, published Paterson’s) – [addendum: copy in British Library – catalogue entry here.] |

| Gala Water, arr. MWT [choir & band?] (1884) |

| The garb of the Gaul, arr. MWT for choir & band (1883) |

| The lass o’ Ballochmyle, arr. MWT for choir and band (1885) |

| The lassie wi’ the lint-white locks, arr. MWT for choir and band (1885) |

| She’s fair and fause, arr. MWT for choir and band (1895) |

| The Maid of Islay, arr. MWT for choir and band (1895) |

| The smiling spring, words by Burns, arr. by MWT for The National Choir [Addendum: Vol.1 p.238 (Parlane, 1891)] |

| The voice of the deep (1883), bass song, written and composed by MWT [Addendum: referenced in a newspaper report of a concert that took place in St George’s Church, Paisley. A positive review!] |

| The Weary day, original words and music, by MWT for The National Choir [Addendum: Vol.1 p.312 (Parlane, 1891)] |

Table 2: Compositions and Arrangements

And recited verses in writing

Ca.1889, Maggie’s name was included in a book, Robert Brown’s Paisley poets: with brief memoirs of them, and selections from their poetry, revealing another facet of this seemingly very modest but quite talented young woman. Five of her poems are included, two of which are on musical subjects: ‘Alone with the organ’, and ‘Verses suggested by a happy musical evening.’ Her poems were noteworthy enough to feature in A History of Scottish Women’s Writing (Douglas Gifford, Dorothy McMillan, 1997). Furthermore, she is on record as having exhibited amateur watercolours in Paisley, although there are no further details of what she painted.

And some there be which have no memorial?

As a spinster, Maggie would probably have been the main carer for her elderly mother; her married sister lived in Bonnybridge, a distance away. Her mother died of senile debility on 20 February 1896 aged 77. Grief-stricken, Maggie died on 12 April the same year, of exhaustion, nervous debility and ‘mania’, having fallen out of her bed in Riccartsbar Asylum. A lengthy, and adulatory obituary appeared in the Paisley and Renfrewshire Gazette. To quote but a fraction of it,

Her well-known musical talents suffered from the wise old proverb, “a prophet”, she was held in high respect by the whole community, and yet it is no less true that in any other community than her native one, she would have commanded higher financial rewards. [She] was very successful as a teacher, and though a stranger would probably have asked and received higher fees, she always commanded a fair share of patronage.

A week later, the same newspaper published the eulogy delivered by the Revd. John Fraser at St George’s Church (‘We make no moan, we utter no cry; we say our heroine is dead’), echoing praise of her many musical talents, and applauding a modest and Christian life well-lived.

Woodside Cemetery has two lairs belonging to the family, bought by Maggie’s father Alexander Thomson. Today’s online database tells us who lies where, but there is no gravestone erected by the family. However, Maggie’s passing did not go unnoticed. The Paisley Choral Union subscribed to erect an imposing marble tombstone, topped with a nine-foot obelisk. (This has sadly fallen off, and lies in two pieces behind the gravestone, on the hillside behind Woodside Crematorium.)

Margaret W Thomson

Died April 12th 1896.

Erected by present and former members of the Paisley Choral Union, as a mark of their esteem and appreciation of her musical services.

(Margaret Thomson’s Gravestone)

To have been commemorated in such generous style gives us some indication of the affection in which Maggie was held, and the talent which she clearly displayed. On a damp, January morning, I paused silently for a few minutes, as squirrels scampered past me, and water gently leaked into my trainers. There was no-one in earshot as I murmured, ‘Maggie, you are not forgotten.’