In our research into the legal deposit music collected in British libraries during the Georgian era, a key thread is obviously the histories of individual collections between then, and now. Two hundred years is a long time, so contemporary evidence is significant.

For example, in 1826, the pseudonymous Caleb Concord wrote in the (short-lived) Aberdeen Censor that the students at Aberdeen’s Marischal College should be more concerned about what had happened to the legal deposit music that had been claimed by Aberdeen’s other higher education institution, King’s College. Corroborating this, Professor William Paul, who had once been librarian at King’s College, told an official commission in 1827, that he believed some of the music had been sold at some time before he went to the college, ie, before 1811. (Commissioners for Visiting the Universities and Colleges of Scotland, Evidence, Oral and Documentary, Taken and Received by the Commissioners … for Visiting the Universities of Scotland. Vol.4, Aberdeen (London: HMSO, 1837). There is evidence for Stationers’ Hall music having been sold at Edinburgh University in the late eighteenth century, too.

In St Andrews, by contrast, there are not only archival records documenting senate decisions about the library, but also the borrowing records, which I’ve written and blogged about quite a bit over the past couple of years – not to mention the handwritten catalogue by a niece of a deceased professor of the University. A payment was made to her in the 1820s, but the catalogue continued to be updated until legal deposits ceased to be claimed by the University in 1836, when the legislation changed. (Miss Lambert married and moved to London in 1832, so the later years were not completed by her.)

Bibliographic Control

In the middle few decades of the nineteenth century, some of the libraries began to attempt better control and documentation of their music. However, I don’t propose to write about every legal deposit library in this posting, because my main reason in writing today is to share a small but interesting excerpt from William Chappell’s first book about English national songs. Now, in my own doctoral thesis and subsequent book, I focused on Chappell’s later work, Popular Music of the Olden Time (1855-1859), and its later iteration, Old English Popular Music. I mentioned that PMOT had grown out of his earlier Collection of National Airs (1838-1840), and I highlighted a few key features of that work.

A Rare Find

Today, sifting through a library donation of largely 20th century scores, I was astonished

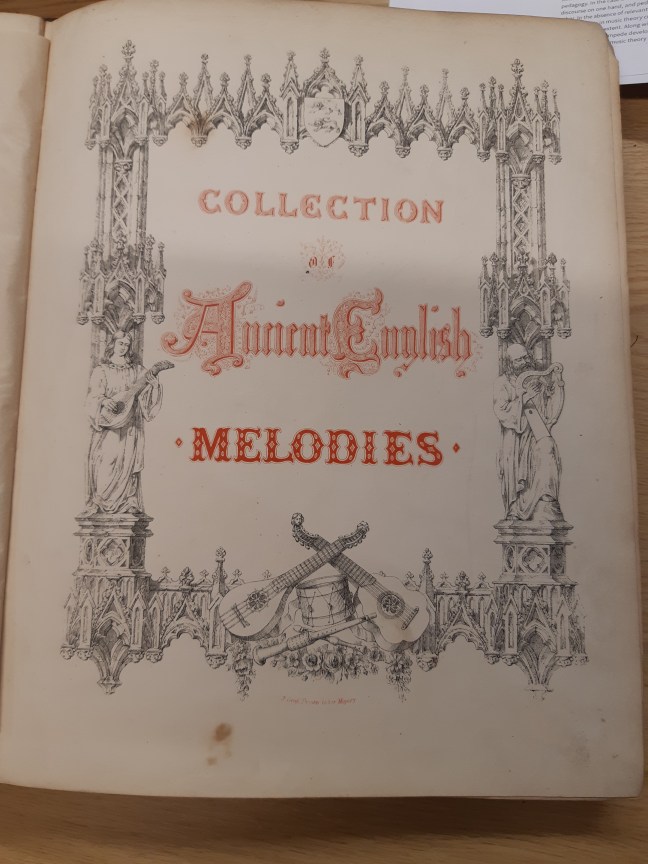

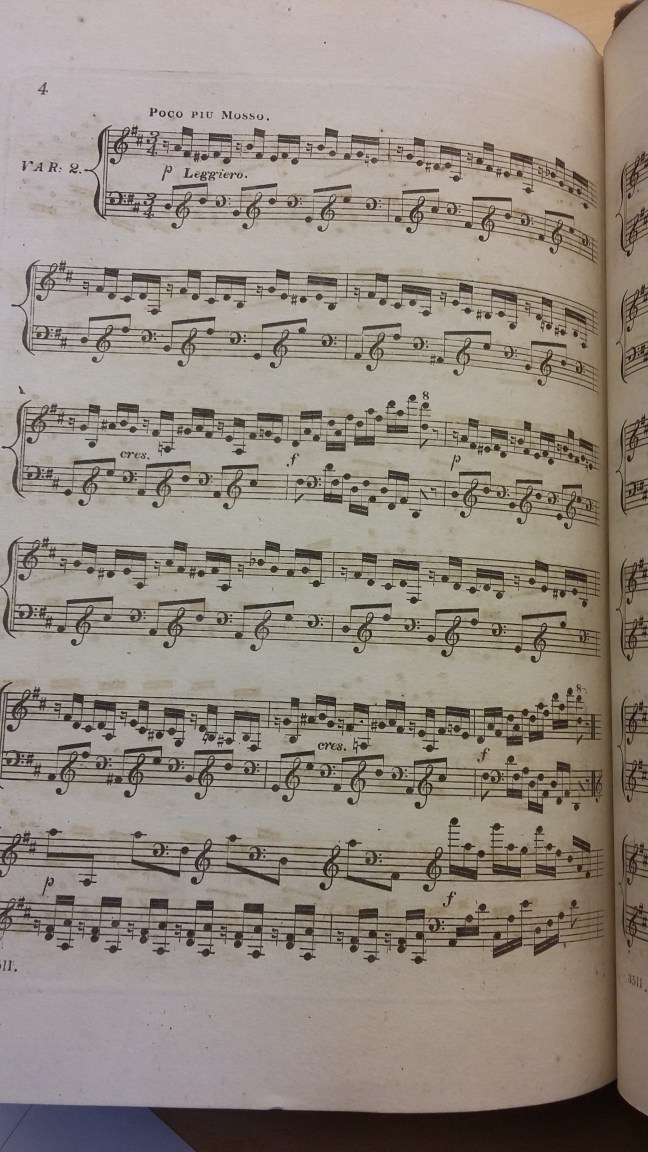

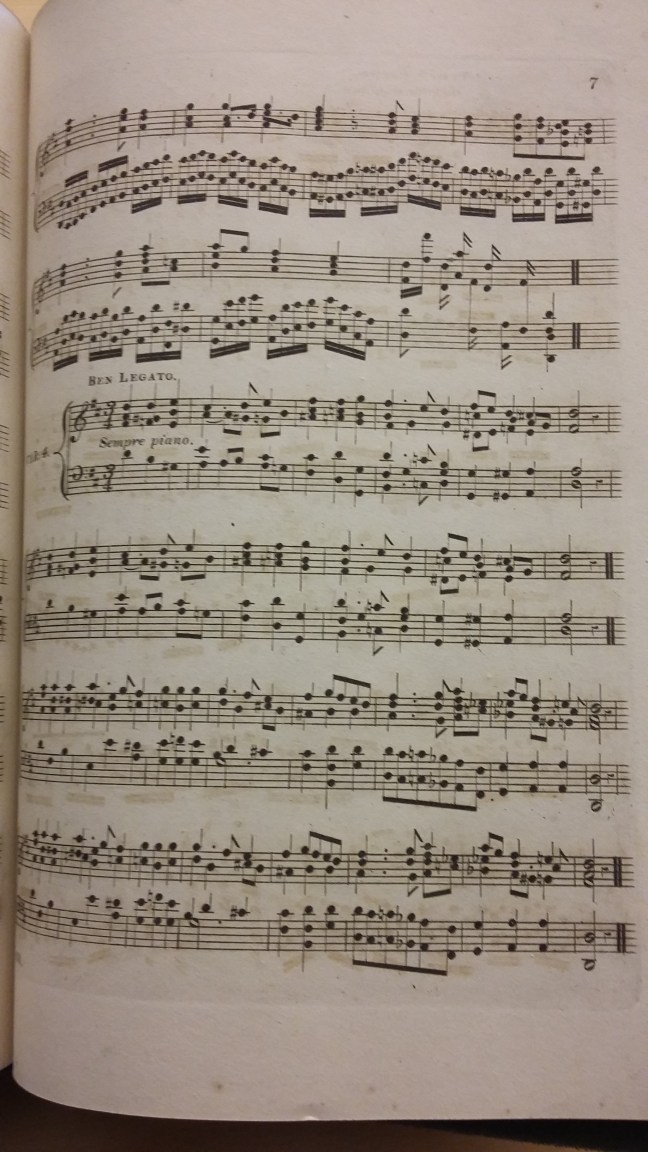

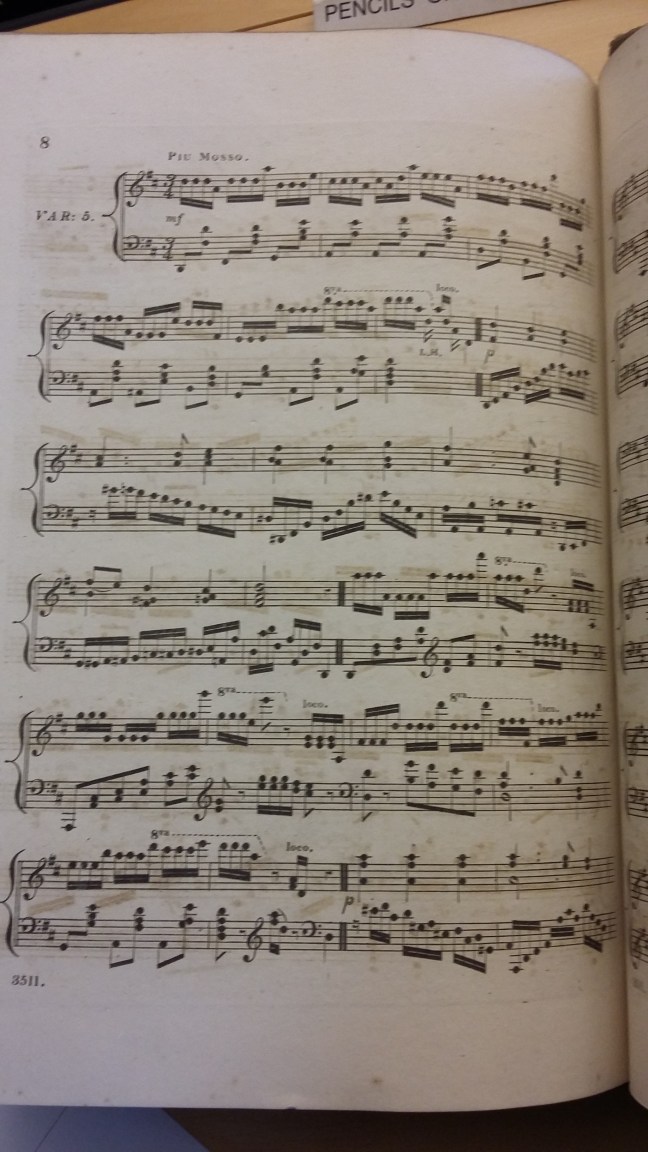

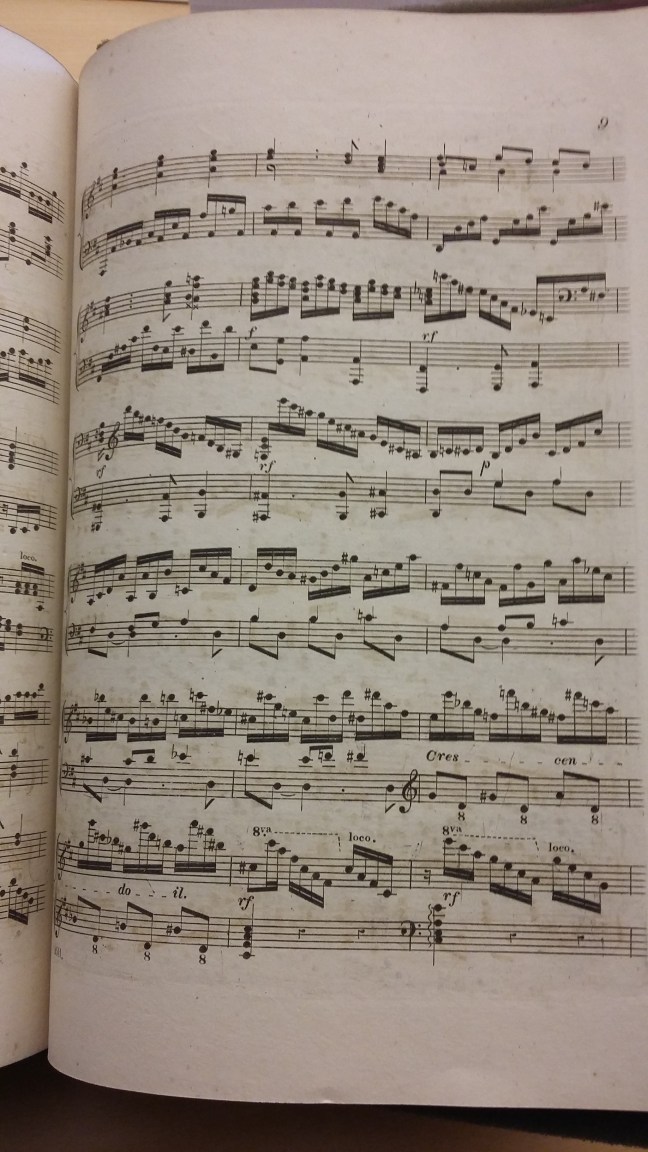

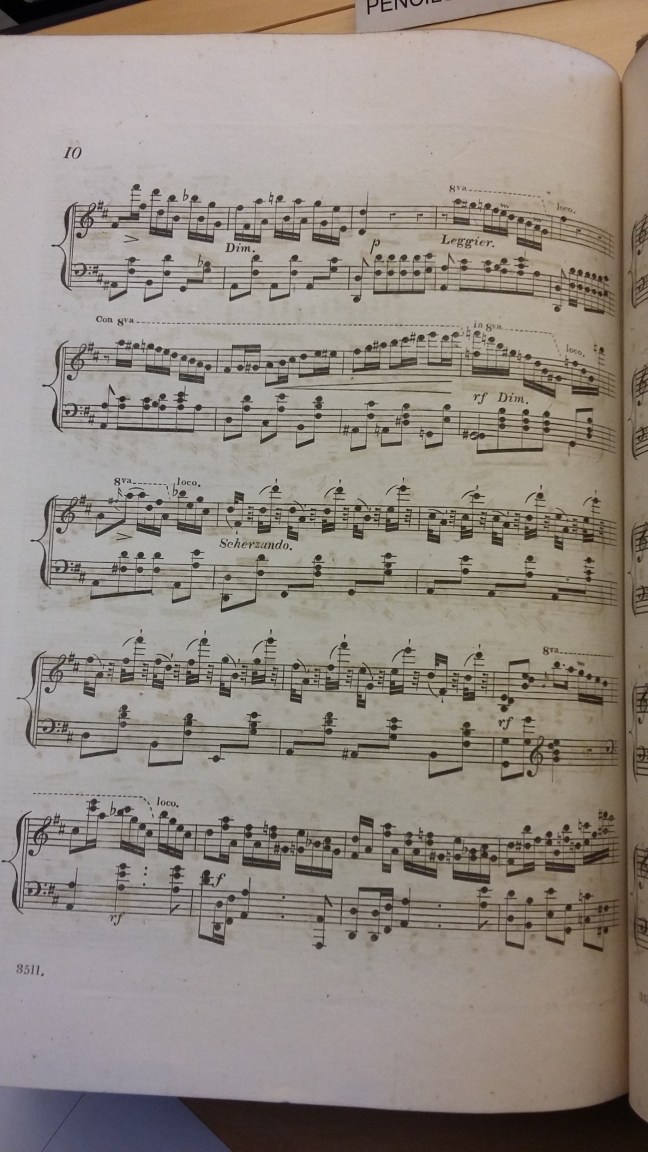

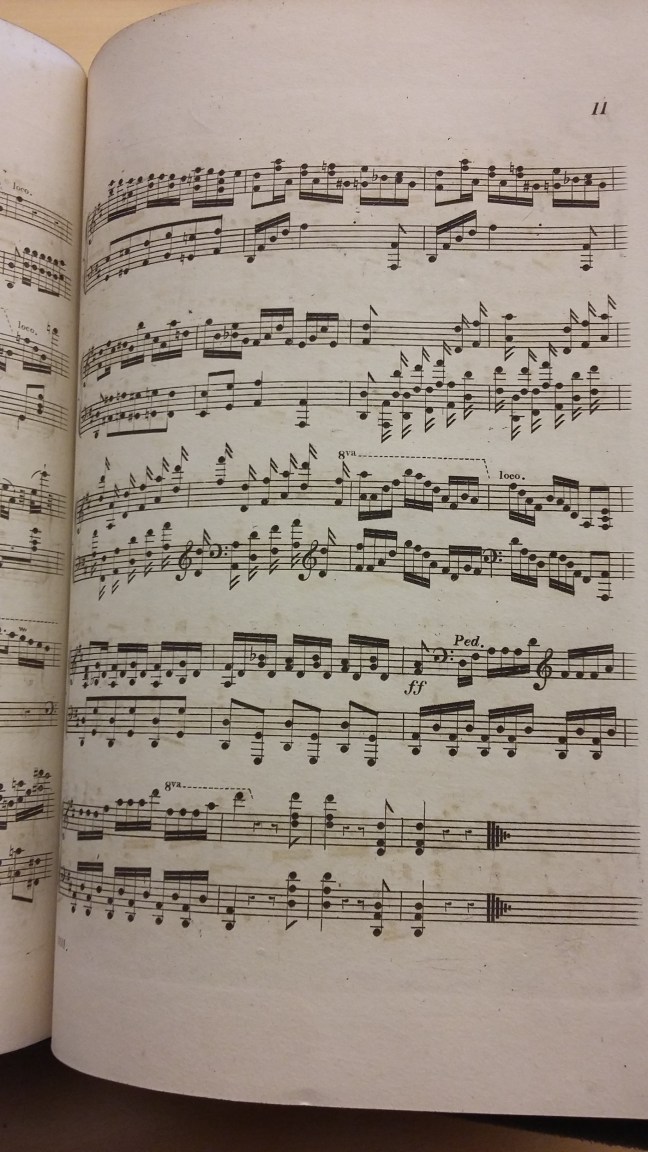

Today, sifting through a library donation of largely 20th century scores, I was astonished to lift two obviously older volumes out of one of the boxes. We’re now the proud owners of the third set of Collection of National Airs known to be held in Scotland. Since I haven’t looked at this title for a decade or so, I leafed through both volumes briefly, to remind myself what they were like. (The volumes had belonged to a Mrs Chambers, and either she or a young relative had practised their drawing skills on the flyleaves, but we’ll overlook those for now!)

to lift two obviously older volumes out of one of the boxes. We’re now the proud owners of the third set of Collection of National Airs known to be held in Scotland. Since I haven’t looked at this title for a decade or so, I leafed through both volumes briefly, to remind myself what they were like. (The volumes had belonged to a Mrs Chambers, and either she or a young relative had practised their drawing skills on the flyleaves, but we’ll overlook those for now!)

Chappell’s work is in two volumes: the first contains the subscriber’s list and a preface, with the rest of the volume devoted to the tunes themselves. The second volume contains commentary, winding up with a conclusion and then an appendix.

Chappell’s work is in two volumes: the first contains the subscriber’s list and a preface, with the rest of the volume devoted to the tunes themselves. The second volume contains commentary, winding up with a conclusion and then an appendix.

England has no National Music

The preface opens with the words which have echoed (metaphorically speaking) in my ears since I first read them:-

“The object of the present work is to give practical refutation to the popular fallacy that England has no National Music,- a fallacy arising solely from indolence in collecting; for we trust that the present work will show that there is no deficiency in material, whatever there may have been in the prospect of encouragement to such Collections.”

Of course, Chappell was preoccupied with national songs (“folk songs”) and ballads – as was I, at the time I first read it. So I hadn’t paid attention to a footnote later in the Preface. But, as I read on, there it was – William Chappell commenting on the legal deposit music in what is now the British Library! It is clear that the music – in Chappell’s eyes, at any rate – was in need of organisation. (We now know that it was much the same in Oxford, Edinburgh or Edinburgh’s Advocates’ Library – the forerunner of the National Library of Scotland.)

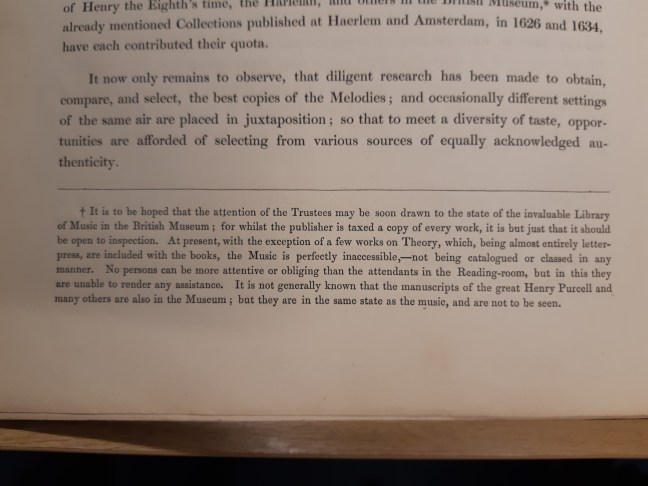

On page iv, Chappell named various key collections of British tunes, naming the British Museum (the forerunner of our British Library) as the repository for some of these collections. A footnote afforded him the chance to make an aside about the contemporary custodial arrangements there.

Attentive, Obliging … Inaccessible, Not Catalogued

“† It is to be hoped that the attention of the Trustees may be soon drawn to the state of the invaluable Library of Music in the British Museum; for whilst the publisher is taxed a copy of every work, it is but just that it should be open to inspection. At present, with the exception of a few works on Theory, which, being almost entirely letterpress, are included with the books, the Music is perfectly inaccessible, – not being catalogued or classed in any manner. No persons can be more attentive or obliging than the attendants in the Reading-room, but in this they are unable to render any assistance. It is not generally known that the manuscripts of the great Henry Purcell and many others are also in the Museum; but they are in the same state as the music, and are not to be seen.”

Changing the subject, it’s interesting for us as modern readers to note that Chappell’s conclusion at the end of the second volume winds up with a sorrowful observation about the decline in musical education, since an unspecified time when music was a key part not only of a young gentleman’s education, but also of young children’s.

Merry England

“The Editor trusts, however, that he has already satisfactorily demonstrated the proposition which he at first stated, viz. that England has not only abundance of National Music, but that its antiquity is at least as well authenticated as that of any other nation. England was formerly called “Merry England.”

Music taught in all public schools

“That was when every Gentleman could sing at sight;- when musical degrees were taken at the Universities, to add lustre to degrees in arts;- when College Fellowships were only given to those who could sing;- when Winchester boys were not suffered to evade the testator’s will, as they do now, but were obliged to learn to sing before they could enter the school;- when music was taught in all public schools, and thought as necessary a branch of the education of “small children” as reading or writing;- when barbers, cobblers and ploughmen, were proverbially musical;- and when “Smithfield with her ballads made all England roar.” Willingly would we exchange her present venerable title of “Old England,”, to find her “Merry England” once again.”

Chappell should read the commentary in today’s social media about the self-same topic!

Today, sifting through a library donation of largely 20th century scores, I was astonished

Today, sifting through a library donation of largely 20th century scores, I was astonished to lift two obviously older volumes out of one of the boxes. We’re now the proud owners of the third set of Collection of National Airs known to be held in Scotland. Since I haven’t looked at this title for a decade or so, I leafed through both volumes briefly, to remind myself what they were like. (The volumes had belonged to a Mrs Chambers, and either she or a young relative had practised their drawing skills on the flyleaves, but we’ll overlook those for now!)

to lift two obviously older volumes out of one of the boxes. We’re now the proud owners of the third set of Collection of National Airs known to be held in Scotland. Since I haven’t looked at this title for a decade or so, I leafed through both volumes briefly, to remind myself what they were like. (The volumes had belonged to a Mrs Chambers, and either she or a young relative had practised their drawing skills on the flyleaves, but we’ll overlook those for now!) Chappell’s work is in two volumes: the first contains the subscriber’s list and a preface, with the rest of the volume devoted to the tunes themselves. The second volume contains commentary, winding up with a conclusion and then an appendix.

Chappell’s work is in two volumes: the first contains the subscriber’s list and a preface, with the rest of the volume devoted to the tunes themselves. The second volume contains commentary, winding up with a conclusion and then an appendix.

Driving back through heavy showers, I was largely oblivious to the weather. I had a pageful of notes to think about and follow up, and the possibility of further future contact. The Aberdeen-Norfolk connection is indeed a good thing, and I’m delighted to have made contact again after a gap of several years.

Driving back through heavy showers, I was largely oblivious to the weather. I had a pageful of notes to think about and follow up, and the possibility of further future contact. The Aberdeen-Norfolk connection is indeed a good thing, and I’m delighted to have made contact again after a gap of several years.