It’s not as though I’m unaccustomed to what I’ve been doing in odd moments for the past few days. Over the years, I’ve opened dozens, indeed hundreds of old song books and other music publications, trying to read their prefaces, annotations and harmonic arrangements as though I were a contemporary musician rather than a 21st century musicologist. Looking at music educational materials is likewise not new to me.

Enter Dr Walford Davies and his The Pursuit of Music

He was the first music professor at the University of Aberystwyth, but he was also hugely popular in the 1920s-30s through his broadcasting work – fully exploiting the new technology of wireless and gramophone for educational purposes, and to share his love of music with the ordinary layman wishing to know more about all they could now listen to. This book was written after he’d mostly, but not entirely retired.

It wasn’t exactly what I expected! If I thought he would write about what made the Pastoral Symphony pastoral, or Die Moldau describe a river’s journey, I rapidly had to change my expectations.

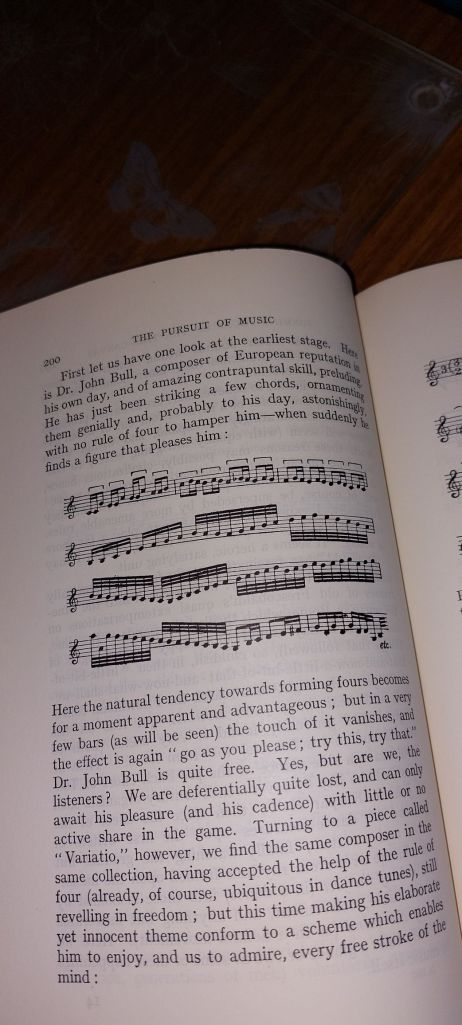

His audience was apparently not just the average layperson, but also young people in their late teens, not long out of school. If the reader didn’t play the piano, they were urged to get a friend to play the examples for them. (Considering the book is over 400 pages, you can imagine how long they’d be – erm – captive!)

And this was aesthetics, 90 years ago. I struggled to get into the mindset of a layperson wanting to know what music (classical, in the main) was ‘about’, without knowing what a chord was, or realising that music occupies time more than space. Would I have benefited from that knowledge? Would being told in general terms what the harmonic series was, have helped me appreciate the movements of a string quartet? Or Holst’s The Planets?

It wasn’t about musical styles over the years. I didn’t read it cover to cover, but neither did it appear to explain musical form and structure as I would have expected.

Davies’ biographer, H. C. Colles, did comment that it was a mystifying book, and suffered from the fact that the author’s strengths were in friendly and persuasive spoken, not written communication.

I’ve only heard snatches of his spoken commentary, so I can’t really say. Apart from which, Colles made an observation about Davies’ written style. Colles was a contemporary authority who knew Davies personally – and he may have been picking his own words carefully, so as not to cause offence. My own disquiet is more a matter of content: was it what his avowed audience needed, to start ‘understanding music’?

I think I have been mystified enough.

I wonder what the Nelson editors made of this book by one of the great names of their age? They published it, and I think regarded him as a catch, but what did they actually think?!

And did the layperson, assuming they got through the 400+ pages, lay it down with a contented sigh, feeling that now they understood music?