There are a few places where my in-laws’ history and my own research findings overlap. Glasgow is one of them, and Greenock is another. I know the stories of three mid-nineteenth century Greenock boys, all with family connections to shipping on the River Clyde: I encountered two of them whilst researching Scottish music publishers, but the other one is indirectly linked to me by marriage.

Allan Macbeth (1856-1910): Athenaeum School of Music Principal

Allan Macbeth was born in Greenock in 1856 to an eminent artist. After the family had moved to Edinburgh, he had two spells studying music in Germany, but he did return to Scotland. He married the daughter of a Greenock builder, ships carpenter, timber-merchant and saw-miller. Between 1880-7, he conducted Glasgow Choral Union.

Between 1890 -1902, he was Principal of Glasgow’s Athenaeum School of Music, building it up to a size barely imagined by the early directors. In 1902, he left to open his own Glasgow College of Music in India Street, taking umbrage after the Athenaeum directors decided they didn’t want a Principal who also taught classes. His own college appears to have died with him when he died in 1910.

Technically capable, in terms of musicianship, he wrote a quantity of lightweight music, eg his Forget me Not intermezzo and Love in Idleness serenata, both of which were subsequently re-arranged for different instrumentations, shortly after his death. Barely any of his music was published in Scotland – It was almost all published in England by a mixture of big and very small names.

Macbeth was one of the arrangers of James Wood and Learmont Drysdale’s Song Gems (Scots) Dunedin Collection, published in 1908 both in London and Boston, Massachusetts. Indeed, my own copy came from Boston, though there had also been an Edinburgh distributor. His Scottish song arrangements were typically late Romantic in style. The collection was aimed at a musically and culturally educated middling class, knowledgeable about Scottish poetry of earlier times. For example, his setting of Walter Scott’s ‘The Maid of Neidpath’ was set to an earlier tune by Natale Corri – hardly of Scottish origin! – with lush harmonies. I wrote about the collection in my A Social History of Amateur Music Making and Scottish National Identity (Routledge, 2025).

Macbeth’s son, Allan Ramsay Macbeth, briefly attended Glasgow School of Art (GSA) as an architectural apprentice before leaving to become an actor, and one of his cousins, Ann Macbeth, became head of embroidery there.

James [Hamish] MacCunn (1868-1916)

Twelve years after Macbeth’s birth, a second musical boy was born in 1868, this time to a wealthy ship-owning family in Greenock. The family firm later went bankrupt, but not before James MacCunn had benefited from a composition scholarship to the newly established Royal College of Music in London at a very young age. Like Macbeth, he left Scotland to further his musical education. He styled himself Hamish to suit his ostentatiously Scottish persona, and spent the rest of his life in England, determined to live in the style to which he had become accustomed. His compositions were on a decidedly larger and more ambitious scale than Macbeth’s, but he perhaps didn’t live up to his early adult promise, and his insistence on flaunting his Celtic origins may ultimately have gone against him. He too gets a mention towards the end of my Social History of Amateur Music Making.

McAulay (McAuley, MacAulay) Hogmanay, 1873

Also in the 1860s, my grandfather-in-law was born in Greenock to a much lowlier family, in 1866. (If you’re trying to calculate how my grandfather-in-law was born 159 years ago, shall we just say that age-gaps account for a lot.) This baby was the second Hugh born in the family, after the first one died of teething. Life wasn’t easy for the illiterate working-class poor; this family had already moved from Ballymoney on the north coast of Ireland, in pursuit of work on the Clyde. His father Alexander worked in the shipyards as a hammerman until his untimely demise one Hogmanay. Last seen on 31 December 1873, Alexander drowned in Albert Harbour and was found a month later. Did he jump, or was he pushed? We’ll never know!

My husband’s grandfather Hugh was later to move his young family to Tyneside in pursuit of work as a ship’s carpenter. Family mythology has various spellings of our name – but since our immigrant Irish McAulays were illiterate, there is no correct spelling. It was spelled however the registrar, or newspaper editor, chose to spell it. There was an embroidered family tale about my Great-Grandfather-in-Law, erasing the embarrassing Hogmanay drowning – and another story about Grandpa-in-Law’s move to Tyneside after a dispute with his foreman (which has every chance of being equally inaccurate).

I can’t help comparing how different were the lives of the two promising young musicians, and the Clydeside then Tyneside shipyard worker who was to thrive on tonic sol-fa, and whose adult family were to make up at least half of their Presbyterian church choir!

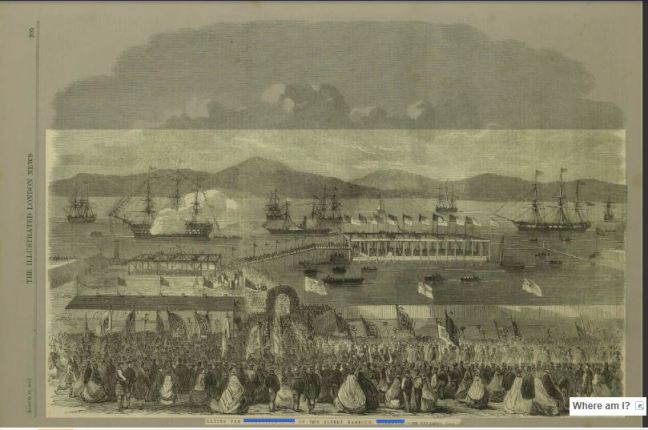

Image: Photo of the laying of the foundation stone, Albert Harbour Greenock, from the Illustrated London News 23 August 1862, p. 9 (British Newspaper Archive)