The government moved the goalposts – when I started work, I imagined I’d have retired by now. Instead, I’ve worked an extra five years, with one more to go. I shall hit 66 in summer 2024. I don’t want to retire entirely, but I must confess I’m utterly bored with cataloguing music! (Except when it turns out to be a weird little thing in a donation, perhaps shining a light on music education in earlier times, or repertoire changes, or the organisation behind its publication – or making me wonder about the original owner and how they used it … but then, that’s my researcher mentality kicking in, isn’t it?!)

Status Quo: Stability and Stagnation

Everyone knows I’m somewhat tired of being a librarian. Everyone knows that my heart has always been in research. Librarianship seemed a good idea when I embarked upon it, and it enabled me to continue working in music, which has always been my driving force. But the downside of stability – and I’d be the first to say that it has been welcome for me as a working mother – has been the feeling of stagnation. No challenges, no career advancement, no extra responsibility. Climbing the ladder? There was no ladder to climb, not even a wee kickstep! (I did the qualification, Chartership, Fellowship, Revalidation stuff. I even did a PhD and a PG Teaching Cert, but I never ascended a single rung of the ladder.)

In my research existence, I get a thrill out of writing an article or delivering a paper, of making a new discovery or sorting a whole load of facts into order so that they tell a story. I love putting words on a page, carefully rearranging them until they say exactly what I want them to say. I’m good at it. But as a librarian, I cannot say I’m thrilled to realise that I’ve now catalogued 1700 of a consignment of jazz CDs, mostly in the same half-dozen or so series of digital remasters. (I’d like to think they’ll get used, but even Canute had to realise that he couldn’t keep back the tide. CDs are old technology.)

The Paranoia of Age

But what really puzzles me is this: when it comes to the closing years of our careers, is it other people who perceive us as old? Is age something that other people observe in us? Do people regard us as old and outdated because they know we’re close to retirement age?

Cognitive Reframing (I learnt a psychology term!)

Cognitive reframing? It’s a term used by psychologists and counsellors to encourage someone to step outside their usual way of looking at a problem, and to ask themselves if there’s a different way of looking at it.

So – in the present context – what do other people actually think? Can we read their minds? Of course not. Additionally, do our own attitudes to our ageing affect the way other people perceive us? Do I inadvertently give the impression that I’m less capable? Do I merely fear that folk see me as old and outdated because I know I’m approaching retirement age? A fear in my own mind rather than a belief in theirs?

How many people of my age ask themselves questions like these, I wonder?

Am I seen as heading downhill to retirement? Increasingly irrelevant? Worthy only to be sidelined, like the wonky shopping-trolley that’s only useful if there’s nothing else available?

Is my knowledge considered out-of-date, or is it paranoia on my part, afraid that I might be considered out of date, no longer the first port-of-call for a reliable answer?

When I queue up for a coffee, I imagine that people around me, in their teens and early twenties, must see me as “old” like their own grandparents. And I shudder, because I probably look hopelessly old-fashioned and fuddy-duddy. But is this my perception, or theirs? Maybe they don’t see me at all. Post-menopausal women are very conscious that in some people’s eyes, they’re simply past their sell-by date. I could spend a fortune colouring my hair, and try to dress more fashionably, but I’d still have the figure of a sedentary sexagenarian who doesn’t take much exercise and enjoys the odd bar of chocolate! (And have you noticed, every haircut leaves your hair seeming a little bit more grey than it was before?)

Similarly, I worry whether my hearing loss (and I’m only hard of hearing, not deaf) causes a problem to other people? Does it make me unapproachable and difficult to deal with? I’m fearful of that. Is it annoying to tell me things, because I might mis-hear and have to ask for them to be repeated? Or do I just not hear, meaning that I sometimes miss information through no fault but my own inadequate ears? Friends, if you thought the menopause was frightening, then believe me impending old age is even more so. I don’t want to be considered a liability, merely a passenger. And I know that I’m not one. But I torment myself with thoughts that I won’t really be missed, that my contribution is less vital than it used to be.

Gazing into the Future

I wonder if other people at this stage would agree with me that the pandemic has had the unfortunate effect of making us feel somewhat disconnected, like looking through a telescope from the wrong end and perceiving retirement not so much a long way off, as approaching all too quickly? The months of working at home have been like a foretaste of retirement, obviously not in the 9-5 itself (because I’ve been working hard), but in the homely lunch-at-home, cuppa-in-front-of-the telly lunchbreaks, the dashing to put laundry in before the day starts, hang it out at coffee-time, or start a casserole in the last ten minutes of my lunchbreak. All perfectly innocuous activities, and easily fitted into breaks. But I look ahead just over a year, and realise that I’ll have to find a way of structuring my days so that I do have projects and challenges to get on with.

Not for me the hours of daytime TV, endless detective stories and traffic cops programmes. No, thanks! Being in receipt of a pension need not mean abandoning all ambition and aspiration. I want my (hopeful) semi-retirement to be the start of a brand-new beginning as a scholar, not the coda at the end of a not-exactly sparkling librarianship career. If librarianship ever sparkles very much!

I’m fortunate that I do have my research – I’m finishing the first draft of my second book, and looking forward to a visiting fellowship in the Autumn. As I wrote in my fellowship application, I want to pivot my career from this point, so that I can devote myself entirely to being a researcher, and stop being a librarian, as soon as I hit 66. And I want to be an employed researcher. I admire people who carve a career as unattached, independent scholars, but I’d prefer to be attached if at all possible!

Realistically, I will probably always be remembered as the librarian who wanted to be a scholar. At least I have the consolation of knowing that – actually – I did manage to combine the two.

![House in South Court, South Street, St Andrews [2016-08-31]](https://karenmcaulay.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/2016-08-31-14.23.15.jpg?w=169)

I’m writing this from Dublin! I’ve spent a fascinating day delving through absolutely enormous guard-books at King’s Inns Library – a historic legal library – and tomorrow I head to Trinity College Dublin.

I’m writing this from Dublin! I’ve spent a fascinating day delving through absolutely enormous guard-books at King’s Inns Library – a historic legal library – and tomorrow I head to Trinity College Dublin.

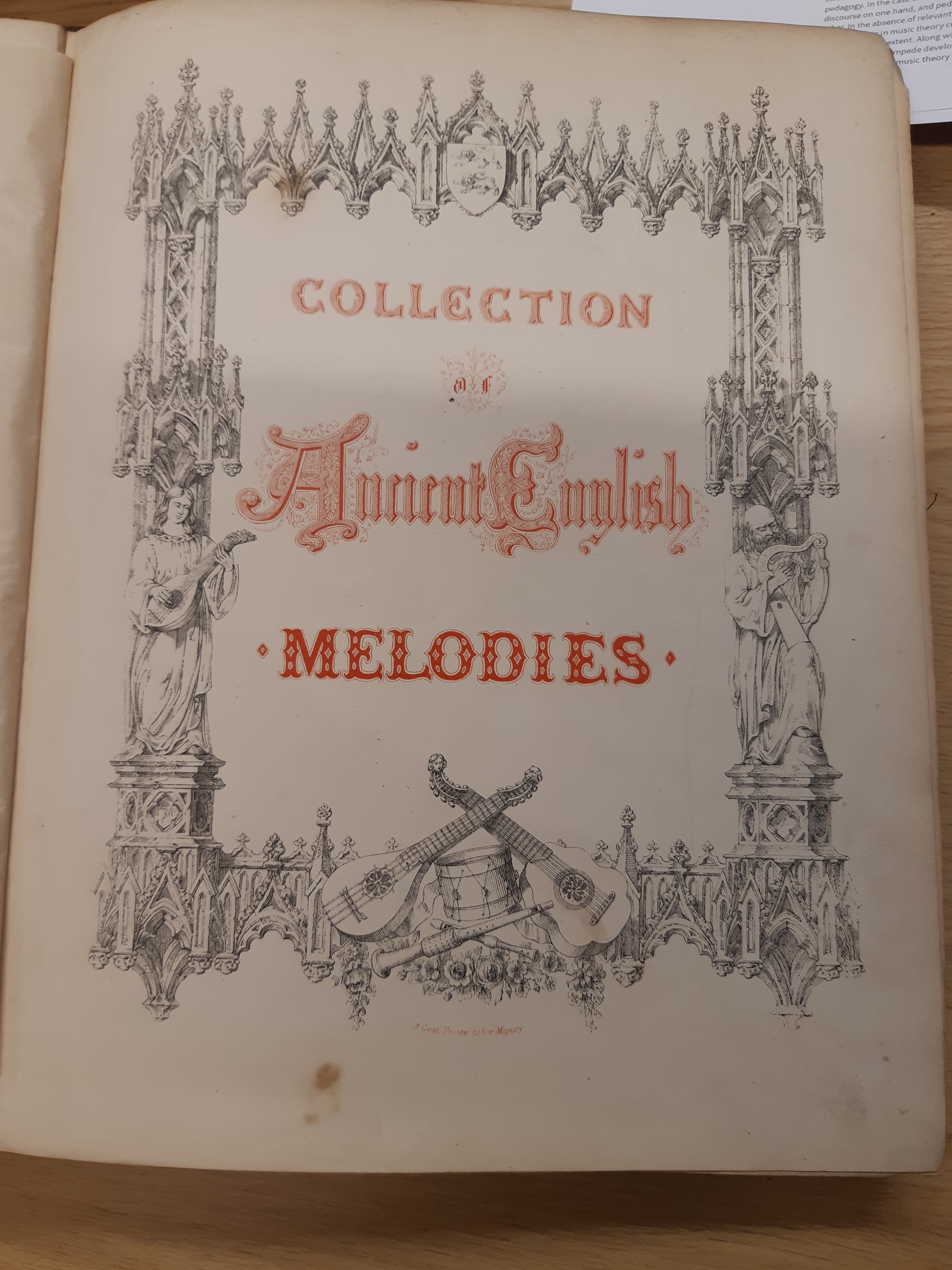

Today, sifting through a library donation of largely 20th century scores, I was astonished

Today, sifting through a library donation of largely 20th century scores, I was astonished to lift two obviously older volumes out of one of the boxes. We’re now the proud owners of the third set of Collection of National Airs known to be held in Scotland. Since I haven’t looked at this title for a decade or so, I leafed through both volumes briefly, to remind myself what they were like. (The volumes had belonged to a Mrs Chambers, and either she or a young relative had practised their drawing skills on the flyleaves, but we’ll overlook those for now!)

to lift two obviously older volumes out of one of the boxes. We’re now the proud owners of the third set of Collection of National Airs known to be held in Scotland. Since I haven’t looked at this title for a decade or so, I leafed through both volumes briefly, to remind myself what they were like. (The volumes had belonged to a Mrs Chambers, and either she or a young relative had practised their drawing skills on the flyleaves, but we’ll overlook those for now!) Chappell’s work is in two volumes: the first contains the subscriber’s list and a preface, with the rest of the volume devoted to the tunes themselves. The second volume contains commentary, winding up with a conclusion and then an appendix.

Chappell’s work is in two volumes: the first contains the subscriber’s list and a preface, with the rest of the volume devoted to the tunes themselves. The second volume contains commentary, winding up with a conclusion and then an appendix.

We tend to take catalogues for granted. We expect them to tell us everything about a book, score or recording – author, title, publisher and publication date, pagination, unique identifying numbers (ISBN, ISMN or publishers’ code), and the contents of an album or collection of pieces. We look for the author or composer, the editor(s) – and expect to be able to know which is which. In modern, online catalogues, this metadata is all carefully entered into special machine-readable fields as a “MARC record”. That’s a MAchine-Readable Cataloguing record.

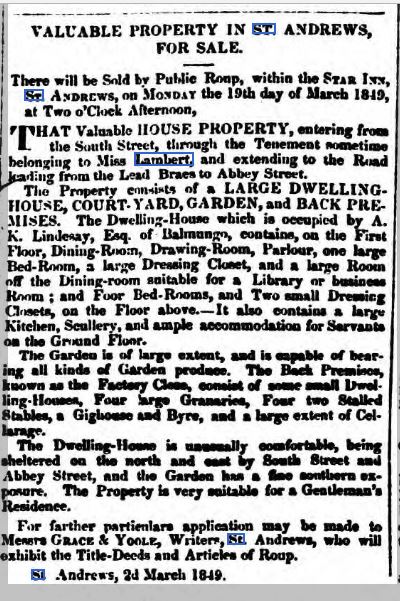

We tend to take catalogues for granted. We expect them to tell us everything about a book, score or recording – author, title, publisher and publication date, pagination, unique identifying numbers (ISBN, ISMN or publishers’ code), and the contents of an album or collection of pieces. We look for the author or composer, the editor(s) – and expect to be able to know which is which. In modern, online catalogues, this metadata is all carefully entered into special machine-readable fields as a “MARC record”. That’s a MAchine-Readable Cataloguing record. But what about our Victorian forefathers or the Georgians before them? By the early 19th century, library catalogues of books were often prepared as printed volumes, but this wasn’t the case for the music I’ve been looking at. Take the University of St Andrews’ handwritten catalogue made by Miss Elizabeth Lambert in the 1820s. If there were (for example) three completely separate pieces making up a set of sonatas or songs, then it was not unusual for her to write a composite entry: “Three sonatas”, “Six Quadrilles on airs from Le Comte Ory” or whatever.

But what about our Victorian forefathers or the Georgians before them? By the early 19th century, library catalogues of books were often prepared as printed volumes, but this wasn’t the case for the music I’ve been looking at. Take the University of St Andrews’ handwritten catalogue made by Miss Elizabeth Lambert in the 1820s. If there were (for example) three completely separate pieces making up a set of sonatas or songs, then it was not unusual for her to write a composite entry: “Three sonatas”, “Six Quadrilles on airs from Le Comte Ory” or whatever. In the Victorian catalogue, music is entered alphabetically by composer, and then alphabetically by title within each composer’s output. However, the alphabetical titles were often alphabetical by genre rather than by exact title, so Selected Marches might be followed by Fourth March then Fifth March and then would come Favorite Quadrilles on airs from Rossini’s Le Comte Ory. (“Quadrilles” are alphabetically after “Marches”, and never mind about the words before them in the title!) Today, we create “uniform titles”, which standardise titles for filing purposes. By comparison, the Victorians had uniform titles in their heads but nothing like that on the catalogue slip!

In the Victorian catalogue, music is entered alphabetically by composer, and then alphabetically by title within each composer’s output. However, the alphabetical titles were often alphabetical by genre rather than by exact title, so Selected Marches might be followed by Fourth March then Fifth March and then would come Favorite Quadrilles on airs from Rossini’s Le Comte Ory. (“Quadrilles” are alphabetically after “Marches”, and never mind about the words before them in the title!) Today, we create “uniform titles”, which standardise titles for filing purposes. By comparison, the Victorians had uniform titles in their heads but nothing like that on the catalogue slip!

It always pays to enquire whether there are other old card catalogues that may not be on general public access. The National Library of Scotland’s Victorian catalogue, and Glasgow’s main public reference library, The Mitchell’s Kidson collection, are just two examples. Because they’re paper slips in long trays, you have to be a bit careful with them, and access may have to be arranged under supervision of a member of staff. But these are valuable resources, and may be the only way of accessing a historical collection of music. Who would have thought it, in these days of online catalogues – or OPACs*, as we fondly refer to them.

It always pays to enquire whether there are other old card catalogues that may not be on general public access. The National Library of Scotland’s Victorian catalogue, and Glasgow’s main public reference library, The Mitchell’s Kidson collection, are just two examples. Because they’re paper slips in long trays, you have to be a bit careful with them, and access may have to be arranged under supervision of a member of staff. But these are valuable resources, and may be the only way of accessing a historical collection of music. Who would have thought it, in these days of online catalogues – or OPACs*, as we fondly refer to them.

Driving back through heavy showers, I was largely oblivious to the weather. I had a pageful of notes to think about and follow up, and the possibility of further future contact. The Aberdeen-Norfolk connection is indeed a good thing, and I’m delighted to have made contact again after a gap of several years.

Driving back through heavy showers, I was largely oblivious to the weather. I had a pageful of notes to think about and follow up, and the possibility of further future contact. The Aberdeen-Norfolk connection is indeed a good thing, and I’m delighted to have made contact again after a gap of several years.