Click here for online poster & more about the speaker!

Don’t worry, it’ll all be in my book, currently at the publishers…

Click here for online poster & more about the speaker!

Don’t worry, it’ll all be in my book, currently at the publishers…

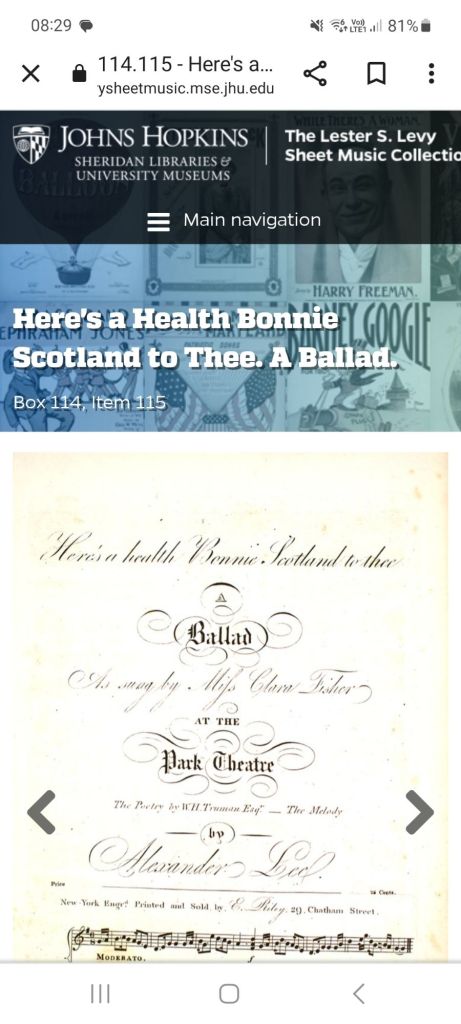

George Alexander Lee published this ‘Scottish song’ in America with A. Fleetwood in New York ca. 1830, whilst this London publication by Alex. Lee & Lee is estimated at 1832 by the National Library of Scotland.

I’ve been wondering how old the expression ‘Bonnie Scotland’ actually is – certainly, this song is sixty years older than the alleged instance in the novel cited on LiveBreatheScotland.com. (I did a search and found ‘bonnie’ but not ‘bonnie Scotland’, so I won’t perpetuate the apparent fallacy by naming the book.)

Has anyone encountered the expression prior to 1830? A friend has suggested the date would be consistent with the years between George IV’s trip to Scotland and before Victoria and Albert’s later acquisition of Balmoral.

A bit of early morning Googling does suggest that the phrase has been popular with visitors and nostalgic expats. Am I right in reaching this conclusion? The fact that the ostensibly Scottish song was first published in New York and London, not Edinburgh or Glasgow – would appear to bear this out. The song appears in Scottish publications a couple of decades later.

For your enjoyment, here’s a Victor recording of 1912, from the Library of Congress. (My understanding is that it is now in the public domain.)

Cover Image by Frank Winkler from Pixabay

Remember, I was looking forward to receiving a pile of old Sol-Fa music the other day? Well, it proved as interesting as I expected. And in amongst the copies that I was expecting, were a couple of choir booklets for ‘The Glen’ concerts – which were annual open-air concerts on the Glennifer Braes in Paisley. I’ve written about these concerts, actually. (You’ll see, when my book comes out!)

As predicted, the programmes were mainly of Scottish songs, but the first song in 1915 was an Irish one – ‘Killarney’. I carefully read the score – I have no problem with the Sol-Fa note pitches, but I can’t have learned the rhythmic notation quite so well when we did it at school! And then, I wondered if I could find a recording of the song, to see if I’d got it right!

I found a YouTube recording of 1905 by Marie Narelle. I have not the first idea who this lady was, but it occurred to me that her singing style probably wasn’t a million miles from what the Paisley United Choirs would have considered a good rendition. It was a strange feeling, to be listening to something 118 years old, and the closest I could get to what was sung on the braes that afternoon.

But that’s not all. On a completely unrelated note, I remember reading about the fascination people had for echoes in the Georgian era, when I was researching the early 19th century Scottish song collector, Alexander Campbell. Alexander Campbell went to Fingal’s Cave with a bagpiper in his boat, just to hear the echo. And I read somewhere that in Ireland, people did a similar thing at Killarney Lake, where they’d take a few instrumentalists in the boat to listen to the echo – but sometimes the musicians would ask for more cash before they’d play a note!

Maybe it was my destiny to find that YouTube recording!

I blogged for the Whittaker Library this morning! It’s about William Moodie’s little book, Our Native Songs. Moodie features in the book that I’ve just finished writing, so I got a bit excited about this little songbook, even though it wasn’t the context in which I had been writing about him before. All the same, it has his words in the Preface, and it has a Glasgow connection, so it was lovely to handle it whilst I catalogued and blogged about it. (And now, I won’t be able to resist investigating the publisher, will I?!)

Read my library blogpost here:-

William Moodie and Glasgow’s ‘Normal School’

(I love the idea that one could whip this tiny book out of one’s pocket if one was in company and suddenly needed the words of a song!)

I’m so pleased with this lovely post, arising from an email exchange with one of our dedicated new Royal Conservatoire of Scotland singing graduates. I posted this on the Whittaker Library blog, Whittaker Live. I hope you like it. I am very grateful to our graduate contributor.

Francis George Scott – Would he make it into your Music Case?

Just a quick reflection, today.

Working on my final chapter, I encountered a composer about whom I knew comparatively little. However, when I discovered he was friendly with one of Scotland’s significant 20th century poets; that the two of them had corresponded extensively; and that the composer set lyrics written by the poet, I thought I ought to know more about both men. I consulted the Oxford Dictionary of Biography. On Amazon, I ordered a poem considered one of the poet’s greatest works. At work, I borrowed a score and a textbook. I also sent out an email, basically asking (in more scholarly terms), ‘is this composer any good?’ (And ‘would you put his songs in your music case, if you were filling it with your favourite repertoire?’)

The outcome was very interesting. I was directed to a singing tutor and a student who had worked on this repertoire. Both sang the composer’s praises – indeed they were enthusiastically generous in their praise.

I also had a response from a traditional music expert: their assessment was quite the reverse. Indeed, it reminded me of what happens when I introduce the songs of Marjory Kennedy Fraser to traditional music students. Looks mingling caution, boredom and blank incomprehension, steal over faces that were only minutes before quite animated and interested.

I’m a musicologist from the classical music tradition, working with supposedly ‘traditional’ folk song collections. Well, commercial collections of ‘traditional’ national songs. I really am stuck in the middle! It’s an interesting place to be.

I think you know my main thoughts about what counts as ‘Scottish’ – I posted about it only last week. However, having just played ‘Highland Cathedral’ as a crowd-pleaser at church this morning, I wondered what Chat GPT thought about that kind of thing. I always feel a bit guilty in two ways: purists quite rightly say it’s not by a Scottish composer, but there I am playing it all the same – whilst people who just like the music don’t want to feel they’re being put down by being ‘educated’ about the fact that it isn’t actually Scottish at all.

Here was my question:- “I’d like to write about the different ways a piece of music can be considered Scottish”

Chat Open AI responded accordingly. This is the link to their answer:- Scottish music explained.

It’s really not a bad response. But of course, I forgot to ask about ‘Highland Cathedral’, which as we all know is not remotely Scottish in origin – it’s just called a Scottish piece and is often played on bagpipes! So I tried again.

My next question:- “Why do some people say that the musical composition, ‘Highland Cathedral’, is not really Scottish?”

I can’t share the same link again, so I’ll show you what Chat Open AI actually said:-

The musical composition “Highland Cathedral” is often associated with Scotland due to its name and the use of bagpipes, which are strongly linked to Scottish music and culture. However, it is true that some people argue that “Highland Cathedral” is not genuinely Scottish in origin.

The composition was actually created by two German musicians, Ulrich Roever and Michael Korb, in the 1980s. It gained popularity as a bagpipe tune and has been performed by various Scottish pipe bands and military bands. The melody and arrangement evoke a sense of Scottish musical traditions and are often heard at Scottish-themed events, including Highland games and military ceremonies.

Critics argue that because the composers are German and the composition was not created within the traditional Scottish musical framework, it does not qualify as an authentic Scottish piece. They contend that “Highland Cathedral” lacks the historical and cultural context typically associated with traditional Scottish music, which often has deep roots in Scottish folklore and history.

However, it’s important to note that the concept of musical authenticity can be subjective, and the definition of what constitutes “Scottish” music may vary among individuals. While “Highland Cathedral” may not have originated from traditional Scottish sources, it has undoubtedly become strongly associated with Scottish culture and is beloved by many as a representation of Scottish musical identity.

Ultimately, whether or not “Highland Cathedral” is considered genuinely Scottish is a matter of personal interpretation and cultural context.

At this point, I’m quite impressed! My essential argument, that Scottishness is a subjective concept, is right there. And it even named the composers – not bad, Chat Open AI!

Another researcher threw out a challenge: Why do some people say that the musical composition “Farewell to Stromness”, is not really Scottish? Now, this is a classical piece by Peter Maxwell Davies. (I played it as a voluntary before the service at church, as it happened!) I was curious to see what Chat Open AI would say. It didn’t exactly muddle things, but there was really no need to talk about traditional music, because this is not traditional!

The musical composition “Farewell to Stromness” is a piece written by the British composer Peter Maxwell Davies. It is part of a larger work called “The Yellow Cake Revue,” which Davies composed in 1980 as a protest against uranium mining in Orkney, Scotland.

While “Farewell to Stromness” was inspired by the Scottish town of Stromness and its local music traditions, some people argue that it is not a traditional Scottish composition. The main reason for this view is that the piece does not adhere to the typical structure and style of Scottish folk music. Traditional Scottish music often features specific rhythmic patterns, melodic ornaments, and instrumental arrangements that are characteristic of the genre.

“Farewell to Stromness,” on the other hand, is a contemporary classical composition that incorporates elements of folk music. It is written for solo piano and has a more modern harmonic language and structure. The piece is often performed by classical pianists and is appreciated for its lyrical and reflective qualities.

While it may not fit the mold of traditional Scottish music, “Farewell to Stromness” is still associated with Scotland due to its thematic connection to the town of Stromness. It is important to note that music, like any art form, evolves and takes on new forms over time. The composition represents a creative interpretation and expression of the composer’s feelings and ideas, which is a common practice in music composition.

Well, I argued back just a little: This music is a classical piece, not a traditional folk tune. It is not a traditional tune from any country!

Chat GPT is so polite in its debates, as you can see:-

You are correct, “Farewell to Stromness” is a classical composition and not a traditional folk tune from any country. I apologize if my previous response was not clear on that point.

As I mentioned earlier, the piece was written by the British composer Peter Maxwell Davies as part of a larger work called “The Yellow Cake Revue.” It was composed in a contemporary classical style and is typically performed by classical pianists.

While the composition was inspired by the town of Stromness in Scotland, it does not adhere to the traditional structures and characteristics of Scottish folk music. It is a unique creation by the composer, and its style falls within the realm of contemporary classical music rather than traditional folk music.

Thank you for pointing out the distinction, and I apologize for any confusion caused by my previous response.

I don’t know if my correction would be incorporated into a subsequent answer, though, since Chat GPT is experimental and based on a snapshot of the internet at a certain point in time. Still, it’s an interesting thing to play with!

Image by Nikolaus Bader from Pixabay

OK. We’re thinking about ‘classical’ music. 🎶

Art music, if you like.

If you’re a serious classical composer, wanting to convey your Scottish identity – but also aspiring to avoid clichés – how do you do it?

Why am I asking you this riddle?

I read in an old newspaper that a certain composer had truly captured ‘Scottishness’ in his music. I didn’t know the piece they were referring to. Did he evoke Scotland in his soundscape? How?

We say that Sibelius’s music evokes Finland. To be truthful, many of us have probably just accepted that it’s a ‘Finnish sound’, making us think of steep valleys, tall pines, and vast echoing lakes. Fair enough. We’ve heard something, and learnt to associate it with a set of visual images.

So what would evoke Scotland? Can we look at some Romantic-era tone-poems and point to elements that sound Scottish, or could only be Scottish?

What are your thoughts about this 🤔

News of a potentially interesting archival item triggers an attack of insatiable curiosity. I must confess that the musicologist is somewhat more triggered than the custodian!

So, I have a few questions that need answered. Where and when was the original owner born? When did they leave Scotland? What did their Scottish ancestry/identity mean to them?

And most importantly, was ‘Scottish’ music a significant part of their repertoire?

As I mentioned in earlier posts, my librarianship is amply qualified, and embodies four decades of expertise, but musicology and research came first. The musicologist is buried beneath the outer librarian, and can’t help bubbling to the surface when an intriguing possibility presents itself!

If I can answer these initial questions satisfactorily, then I’ll want to explore further. I think you can guess what I need to do this morning!

AND LATER …

Well, the original owner called themselves Scottish. But they were born in England of a Scottish mother. Should I order their birth certificate? It’s not cheap, and could arrive too late to be useful. But … !

You can tell when I’m using avoidance tactics on a writing day! But the pictures I’m about to share with you come from an old instrumental Scottish song medley, and it was in the pile of papers that simply had to be sorted out. It’s a library copy, so I can’t actually keep it – I thought I’d take a few snaps just to remind myself what it’s like.

It comes from a series of 48 medleys published by arranger Carl Volti for the London firm, Ascherberg, Hopwood and Crew. This is a series ‘arranged expressly for AMATEURS‘. Oh, what almost limitless fun the great-great aunties and uncles would’ve had, considering each contained at least four different ‘Scotch Airs’! Volti had other arrangements published by Scottish music publishers – but he clearly wasn’t prepared to limit himself to Scotland!

Historically-informed performance practice is very much a buzz-word in music conservatoire circles. The more closely I looked at this piece of music, the more little hints I gleaned about the expectations around its performance.