Forgive me – combining two of my passions, I have to share this article!

Long after their iconic American quilts caught the art world’s attention, the Gee’s Bend artisans are taking control of their legacy.

Dr Karen McAulay explores the history of Scottish music collecting, publishing and national identity from the 18th to 20th centuries. Research Fellow at Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, author of two Routledge monographs.

Forgive me – combining two of my passions, I have to share this article!

Long after their iconic American quilts caught the art world’s attention, the Gee’s Bend artisans are taking control of their legacy.

Spotted on Twitter, shared in haste – this might be of interest to network readers:-

The full CFP can be read in Marten Noorduin’s recent tweet

And here’s the journal itself:-

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/nineteenth-century-music-review

If you’re rushing to submit a proposal, then the following whispered (well, tweeted) insider comment might make you feel a bit less stressed:- “Officially the deadline is today, but I won’t actually be looking at them until Monday morning. Anyone who sends me an abstract before 9 am on 6 February will still be considered!”

By and large, this book is aimed at book and publishing historians – it enumerates the contents of the Stationers’ Company Archive from 1554-1984, at Stationers’ Hall. The compiler, Robin Myers, was for a long time Honorary Archivist there. (She has the status of Liveryman at the Stationers’ Company.)

By and large, this book is aimed at book and publishing historians – it enumerates the contents of the Stationers’ Company Archive from 1554-1984, at Stationers’ Hall. The compiler, Robin Myers, was for a long time Honorary Archivist there. (She has the status of Liveryman at the Stationers’ Company.)

Not the first attempt at documenting this complex body of material, but certainly the most comprehensive, I commend especially the Preface (xiii-xiv) and Introduction xvii-xxxvii), which gives an overview of the history of the Archive. Significantly, the creation of a proper muniment room in 1949 made visits more convenient for researchers, and also saw the awakening interest of musicologists looking for first London editions by famous composers.

Next, cast your eye over the Contents, and in particular Section I – the Entry Books of Copies & Register Books 1557-1842; Registers of Books Sent to Deposit Libraries 1860-1924; a Cash Book & Copyright Ledger Book 1895-1925; and Indexes of Entry Books 1842-1907 appear between pp.21-30. The Entry Books cover several years at a time for the earliest period, and a couple of years at a time for the era that our project has been covering. As I may have mentioned already, I’m quite interested in the book commencing June 1817, and we find in the listing that the wording, ‘Published by the author and his property’ “begins to appear not infrequently in this volume.” This would seem to imply a greater sense of intellectual property, although there may be another more technical explanation of which I’m not aware!

Much of the rest of the book concerns leases, freedoms, wardens’ vouchers and other documentation which are maybe of little concern to the average musicologist, but it would do no harm to glance through the contents if only so that you know what else is there. A complicated web of documentation of which many of us are blissfully unaware!

Myers, Robin (ed.) The Stationers’ Company Archive 1554-1984 (Winchester: St Paul’s Bibliographies, 1990) ISBN 0906795710

The records of the Stationers’ Company are now available as digital images via publisher Adam Matthew: Literary Print Culture: the Stationers’ Company Archive, 1554-2007. As well as the records themselves, there’s also a wealth of background information, including commentary by Robin Myers. You can view a short YouTube video here.

Weekend frivolity on Facebook!

Weekend frivolity on Facebook!

Everyone loves a good CFP, and I’m delighted to share this particular CFP, which I’m quite excited about:-

The British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

is proud to host

The International Congress on the Enlightenment

on behalf of the

International Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (ISECS)

at the University of Edinburgh, 14-19 July

Theme: ‘Enlightenment Identities’

Call for papers link, please click here.

It is an inescapable fact that many a late Georgian or early Victorian music cabinet must have contained at least one set of piano variations on an operatic theme by Rossini. There are just so many of them! Since they proliferated in the 1820s (ie the last decade of Rossini’s operatic compositional phase, and the era when he also visited Britain), you won’t find them listed in Kassler’s Music Entries at Stationers’ Hall – his bibliography ends in December 1818. But you have only to search Copac or glance at St Andrews University Library’s listings, to see how many composers were inspired to write virtuosic variations on the great man’s tunes.

What did Rossini think of this, I wonder? I’ve only started to scratch the surface of this particular enquiry, but to date I’ve discovered only that copyright legislation was not as advanced in Italy as it is in the UK. What’s more, there may not be very many extant letters by the great man from the 1820s, and that the authoritative modern edition of his letters is in Italian. I do know Rossini would have been very conversant with legal documents, considering the number of contracts he signed for his many, many operas. None of this tells me (yet!) what Rossini thought of other composers making free use of his lovely melodies.

What I do have is William Lockhart’s article in Music and Letters (vol.93 no.2, 2012), ‘Trial by ear: legal attitudes to keyboard arrangement in nineteenth-century Britain’; Charles Michael Carroll’s ‘Musical Borrowing – Grand Larceny or Great Art?’ in College Music Symposium (vol.18 no.1, 1978); and Derek Miller’s Copyright and the Value of Performance, 1770-1911 (2018). I shall in due course have a couple more books on Rossini, so I haven’t yet given up on finding out how he felt about this evidence of his popularity. Maybe he just felt flattered – but I’d love to find his own words on the subject!

As for his published letters? Well, I may have to look for them. I know a little Italian, thankfully. But meanwhile, if you know anyone who has read the recent edition, please do let me now! I’d be deeply grateful!

I’m delighted to introduce today’s blogpost by Andrea Cawelti, who is the Ward Music Cataloger at Houghton Library, Harvard University. Andrea attended a course at the American Rare Book School a couple of years ago, and is keen for everyone to know what a wonderful opportunity it would be for anyone who could attend this year’s course. I shared a link to Andrea’s reflections on the course, which she authored for the Houghton Library blog last year – you’ll find the link in the posting below. Now you can read more about it – if you manage to get there, do please consider sharing your own experiences here!

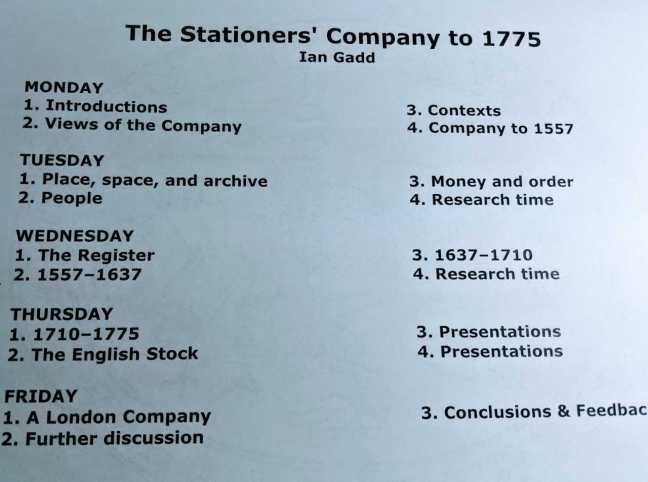

Fellow readers of Claimed from Stationers’ Hall may be aware that the American incarnation of Rare Book School has offered a course on the Stationers’ Hall since Peter Blayney, one of the stalwart fathers of research on the Stationers, taught the course in the 1990s. But I see that applications have been opened today for this summer course, now taught by Professor Ian Gadd, so I’d like to share a bit about my excellent experience in taking this course in 2016, as prompt applications are usually the most successful.

This term, as in 2016, the course will be held in Philadelphia, June 2-7, at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania, with reasonably-priced and comfortable dorm space available within easy walking distance through the picturesque Penn campus. As this course represented my first experience at the Kislak Center, I was delightfully surprised by our genuine welcome, and helpful assistance by the staff, both of the library and those in attendance from the Rare Book School, even though this wasn’t their turf. The Center holds significant hand-press material for examination and project fodder, and Penn Libraries holds a complete set of microfilms of the Stationers’ Company registers and archives, which we consulted extensively for our work.

As with all RBS courses, ample opportunities are presented for individual discussion, questions, and networking, including regular morning and afternoon breaks, lunches, and receptions. Evenings often include programmed activities from lectures to film presentations, and during my course, there was an excellent presentation by Lynne Farrington, senior curator at the Kislak, on American subscription publishers and their German-American readers. Dr. Farrington provided a fascinating overview of the American subscription publishing industry, and how it was utilized for foreign-language titles to be sold through the subscription network. The lecture was accompanied by a hand-on exploration of subscription samples from several of the Kislak’s collections.

Enough of that, you may say, what about the course itself?!?!?! Well, first of all, I should mention that I arrived with a specific agenda, which was to familiarize myself with the Registers, what was in them of a music format, and to learn how to use the microfilms most effectively (Harvard, too, holds a complete set of these microfilms).

Like many of you I’m sure, I’ve had cases where I’d hoped to find a specific date in the 18th century when something had been published, or to establish some kind of sequence for several publications, and had been frustrated by my inability to harness these resources. Now of course, newer products are available, including the Literary Print Culture online access, which Professor Gadd has now incorporated into the course. Still, the navigation of this product isn’t straightforward, and one really needs to know what one is doing before attempting to use, or it is easy to get completely lost.

As you can see, the schedule was laid out to allow us a proper introduction to the history of the company and its archives: Professor Gadd offered spirited presentations on each aspect, as well as providing references to online and printed documentation which would be of use later in our explorations. Each of us was then tasked to research and present on some topic of particular interest to us (see “research time” and “presentation time” in the daily schedule). I chose a particular segment of time and explored all of the Registers chronologically to gain an idea of what music was being brought to the Stationers for registration between 1799 and 1804. Several of my discoveries ended up in our Houghton Blog, which presents a bit more information for those who are interested.

I had honestly come into this course completely unaware of how extensive the Stationers’ archives were apart from the Registers! Learning more about the “people” documentation was particularly eye-opening, and quite helpful in my cataloging. The online index to the London Book Trades for instance, based on the Stationers’ archives is great for finding more information on printers when researching, creating authority records, or for investigating connections between people. As always, Professor Gadd provided helpful hints: don’t use the “search” box, just go directly to the “index – names”. There were so many trails of bread crumbs offered to us, that who could remember them all (certainly not I!) Knowing this, the professor provided us with an extensive workbook to take home, complete with bibliography and most useful for me after the fact, an overview of the most important copyright legislation affecting just what was registered with the Company.

While this course only goes up to 1775, and consequently doesn’t cover some of the most influential music-related legislation, suggested readings within provide an appendix as it were, and after going through the history before 1775, reading forward into the 1790s was not difficult. Additional revealing segments covered what species of books were included in the English Stock and why this was important, and an introduction to Edward Arber’s term catalogues – keyword-searchable, and covering (among others and appendices) periods into the 18th century. A mind-boggling amount of work, which doesn’t include that much music but is well worth a look.

Two and a half years later, am I glad I took the course? You bet I am; it has proved to be perhaps one of the most useful courses I’ve taken at RBS. Possibly more so for me, because I was essentially ignorant of so many details of the Stationers’ history, but I would heartily recommend this to anyone preparing to work with, or already working with 17th to 18th century music. The context will provide you with an invaluable overview of how printing functioned in Britain, and how and why and what was registered. I hope that I’ve given something of the flavor of the course, and if anyone has questions about how RBS works, please do ask the RBS:-

https://tinyurl.com/RBS-ApplyTo-Courses

There are links throughout the site, and you’ll find that the RBS is prompt and efficient in their communications.

Good luck and good researching!

Andrea Cawelti

Ward Music Cataloger

Houghton Library

Harvard University

Here’s a fantastic webpage devoted to the exhibition that Cambridge University Library mounted last year. It’s an excellent read, and I’ve got the link saved for addition to the next update of our network music legal deposit bibliography. But I can’t wait to share it with you, so here it is – for your mindful enjoyment:-

https://www.cam.ac.uk/TallTales

(I confess, I have just sauntered via the Amazon page to buy Stephen Fry’s novel, The Liar (2004) for my Kindle. It’s set in the University Library. But that’s for leisure reading, so I must leave it aside for a while!)

This is turning into a busy week! Here’s another interesting call for essays, this time from the Women’s Study Group. Picture me, if you will, twirling like a top as I decide which of all these opportunities to turn my attention to first!

Quoting, with permission, from the email that was kindly forwarded to me:-

“The Art and Science of Collecting in Eighteenth-Century Europe

Edited by Dr. Arlene Leis and Dr. Kacie Wills

“We are inviting chapter abstracts for a collection of essays designed for academics, specialists and enthusiasts interested in the interrelations between art, science and collecting in Europe during the long 18th century. Our volume will discuss the topic of art, science and collecting in its broadest sense and in diverse theoretical contexts, such as art historical, feminist, social, gendered, colonial, archival, literary and cultural ones. To accompany our existing contributions, we welcome essays that take a global and material approach, and are particularly keen on research that makes use of new archival resources. We encourage interdisciplinary perspectives and are especially interested in essays that reveal the way in which women participated in art, science, and collecting in some capacity.

“The compendium will consist of around 15 essays, 6000 words each (including footnotes), with up to four illustrations. In addition to these more traditional essays, we are looking for shorter (circa 1,000 words) case studies on material objects pertaining to collections/collectors from that period. The subject of art, science and collecting will also be central to these contributions. These smaller pieces will each include one illustration. The following topics/case studies are particularly desired:

“All inquiries should be addressed to Arlene Leis, aleis914@gmail.comor Kacie Wills, kacie.wills@gmail.com

“Essay abstracts of 500 words and 300 word abstracts for smaller case studies are due January 30, 2019 and should be sent along with a short bio to: artsciencecollecting@gmail.com

“Finished case studies will be due July 30, 2019, and due date for long essays will be September 30, 2019.

Must be the start of the year – there’s a sudden outpouring of calls for papers, conference registrations and other exciting challenges. Here’s one for this morning – Musica Scotica is a network I’ve long been associated with.

Friday 3 – Sunday 5 May 2019 (Tolbooth, Stirling)

Registration for the Musica Scotica conference is now open. It is posted on Musica Scotica’s Facebook page:- https://www.facebook.com/events/374235653379262/

Musica Scotica homepage: http://www.musicascotica.org.uk/