I’ve written quite a bit about women in musical history, so I’m adding something to the top of this post every couple of days during Women’s History Month – mostly flashbacks to women musicians I’ve researched, but some other discoveries too. (I’ve been shifting things around to a more chronological order, but I’ve always added the new bit first!) You’ll find more musicians than composers in this posting, just because of my own recent research.

Sometimes I look at the history of women musicians from the point of view of good library provision for our readers, whilst at other times my own research interests are foremost. It just depends on the day of the week, because I currently occupy two roles in the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. For 3.5 days a week, I’m a librarian. For 1.5, a postdoctoral researcher.

15. The Ketelbey Fellowship

It’s a whole year since I learned that I had been awarded the first Ketelbey postdoctoral research fellowship at the University of St Andrews. Scholar Doris Ketelbey was a significant figure in the history of the department. I felt highly honoured to have been the first Ketelbey Fellow from September to December 2023.

14. Representation of Women Composers in the Library

I couldn’t resist adding the open access article I published about my EDI activity in our own Whittaker Library:-

‘Representation of Women Composers in the Whittaker Library’, Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice. Vol. 11 No. 1 (2023): Special Issue on Breaking the Gender Bias in Academia and Academic Practice, 21-26. (Paper given at the International Women’s Day Conference hosted by the University of the Highlands and Islands, 2022.) DOI: https://doi.org/10.56433/jpaap.v11i1.533

13. New Books for the Library

It’s a privilege to shape a library collection, so I’m pleased to have just ordered and catalogued several relevant books this month.

- Susan Tomes, Women and the Piano: a History in 50 Lives (Yale University Press, 2024) Read more about it on the publisher’s website, here. In actual fact, it’s the fourth title by this author that we now have in stock. So if readers like this, they might like the earlier three, too!

- Margaret C. Watson, Women in Academia : Achieving our Potential. (Market Harborough : Troubadour, 2024). Not a book about women in history, but very much for women in the present day!

- Gillian Dooley, She played and sang: Jane Austen and Music (Manchester University Press, 2024). Back to history again.

- Women and Music in Ireland / ed. Jennifer O’Connor-Madsen; Laura Watson & Ita Beausang (Boydell Press, 2022)

Moreover, there’s a new Routledge book coming out this summer – I have ordered it for the Whittaker Library. Of course, I may have retired from the Library by the time it arrives. This just means I won’t need to catalogue it! I’ll still be a part-time researcher, so I’ll be able to read it:-

- The Routledge Companion to Women and Musical Leadership: The Nineteenth Century and Beyond / Edited By Laura Hamer, Helen Julia Minors. (2024)

12. Jessy McCabe’s Petition

It’s some years now, since a single-minded schoolgirl decided action was necessary. In 2015, Jessy McCabe noticed that Edexel had no women composers in the A-Level Music syllabus, and successfully petitioned to rectify this, via Change.org. I found out about her impressive initiative when I was beginning to start serious work on building up our library collection to include more music – contemporary and historical – by women and people of colour.

Jessy is now a Special Needs teacher. I’m sure she’ll go far.

11. Forgotten Women Composers

Part of academia entails sharing research outcomes beyond the ‘ivory walls’. It’s called public engagement, and that’s the opportunity I seized when my old friend The People’s Friend magazine commissioned me to write a feature back in 2020.

- The sound of forgotten music: Karen McAulay uncovers some of the great female composers who have been lost from history’, in The People’s Friend, Special Edition, 11 Sep 2020, 2 p. (Dundee : D C Thomson). I blogged about it at the time (here).

10. Late Victorian Women Musicians

Since my more recent research has focused on the late Victorian era and the first part of the twentieth century, you’ll not be surprised to find that I found some interesting Scottish women musicians of that era! They are forgotten today – but I’ve done my bit to raise their profiles!

- Newsletter article, ‘‘Our Heroine is Dead’: Miss Margaret Wallace Thomson, Paisley Organist (1853-1896)’, The Glasgow Diapason, March 2023, 10-15. (You can find this article in full on this blog)

- ‘An Extensive Musical Library’: Mrs Clarinda Webster, LRAM, Brio vol.59 no.1 (2022), 29-42 (a late Victorian head teacher who founded a music school in Aberdeen, and later did a national survey of music in public libraries – which she presented to the Library Association!)

- A Scottish woman headteacher in 1906 (a blog post, September 2023)

- In October 2023, I pondered about Mr *and Mrs* J. Spencer Curwen (amongst others) in another blog post, when I remarked upon early twentieth century attitudes to folk song.

9. In Praise of Music Cataloguers! Introducing Miss Elizabeth Lambert

Before I started the Claimed From Stationers’ Hall music copyright network, I had spent some months researching the wonderful late 18th and early 19th century music copyright collection at the University of St Andrews. A key resource was the handwritten catalogue in two notebooks, largely compiled by Miss Elizabeth Lambert (later to become Mrs Williams, when she married and moved to London.)

I just love the fact that this earnest young woman (I’m going out on a limb here, but I’m pretty sure she must have been earnest!) created a useful resource which would help everyone get maximum use out of the music repertoire that other libraries were less than impressed by. So we had Elizabeth cataloguing the collection, and numerous men and women, friends of the professors, making use of it. I blogged about her, and eventually wrote an article for the Edinburgh Bibliographical Society, mentioning her again.

- Blogpost: ‘A labour of love for Miss Lambert’, (2019)

- ‘A Music Library for St Andrews: use of the University’s Copyright Music Collections, 1801-1849’, in Journal of the Edinburgh Bibliographical Society no.15 (2020), 13-33.

8. Was there a Harp at St Leonard’s School?

Some time ago, I blogged about an instruction manual for harp, which the Bertrams borrowed from St Andrews University Library:-

The library’s copyright collection of music was a boon for middling class women like headmistress Mrs Bertram, her teacher daughters and their pupils. It does lead one to wonder if they had a harp at the school. I checked their borrowing records for more evidence. They certainly borrowed several volumes which included harp music.

7. Students but not at University? Educating Young Women

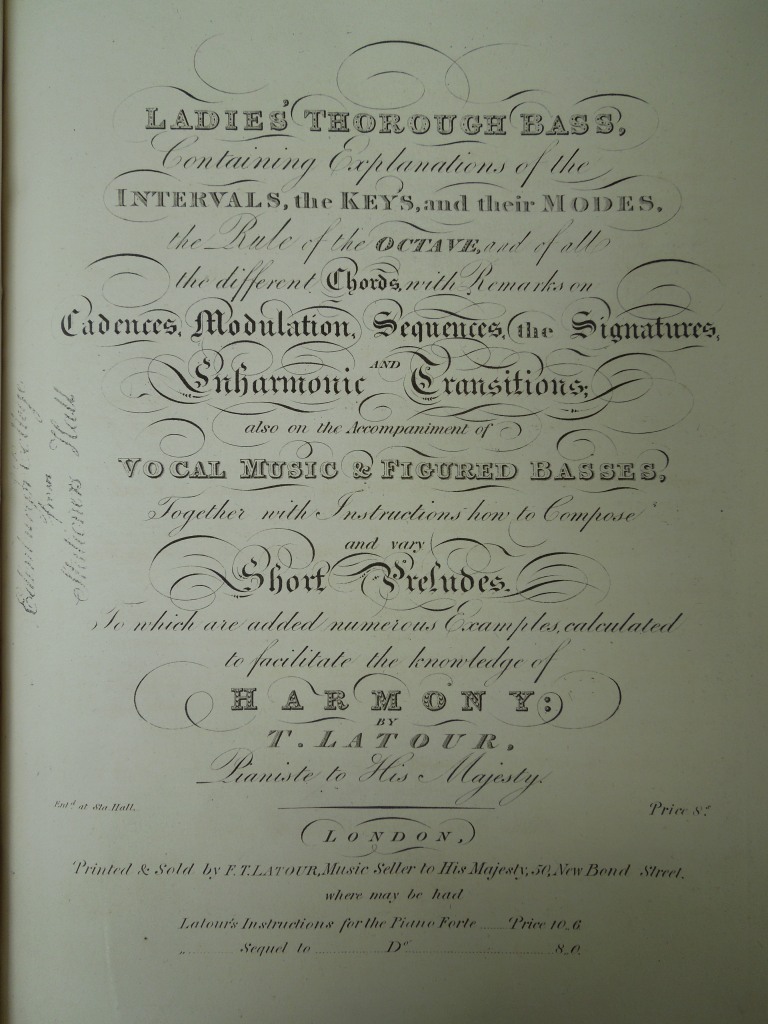

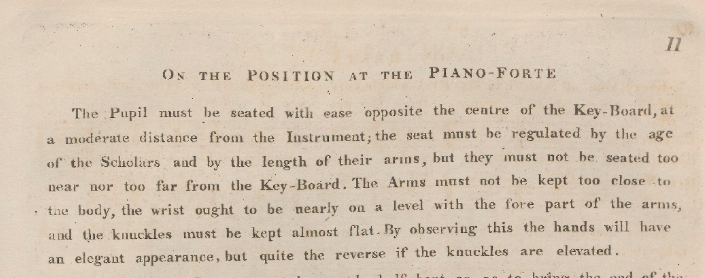

It’s time to turn to piano teacher Mr T. Latour. I’d like to refer you to my June 2018 blog post about women in St Andrews using pedagogical musical material in the early 19th century. Possibly the self-same young ladies attending, or having attended Mrs Bertram’s school?! The illustration features a young woman – probably just approaching or about marriagable age – at an upright piano. The abundant floral arrangement atop the piano (quite apart from sending shivers down the housekeeper’s spine every time the young pianist played too enthusiastically) suggests a well-to-do household. Following Latour’s instructions, the pianist has elegantly flat hands …..

6. Not my work – but very timely for WHM 2024]

I’m not posting anything relating to my work today, but I saw mention of a great new article by Dominic Bridge the other day, so I thought I’d share details here. It’s a fascinating read. The Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies is part of the Wiley Online Library:-

- Bridge, Dominic James Ruggier, ‘A Musical Bouquet for the Ladies’: Gendered Markets for Printed Music in Eighteenth-Century England, Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 6.4 (2023), pp.499-519

5. Jointly authored with Brianna Robertson-Kirkland: ‘My love to war is going’: Women and Song in the Napoleonic Era

We published this article in the Trafalgar Chronicle, New Series 3 (2018), 202-212. My own observations were based on music I had found in the Legal Deposit Music at the University of St Andrews, whilst Brianna had already founded EAERN (Eighteenth-Century Arts Education Research Network) jointly with Dr Elizabeth Ford, funded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

4. Forgotten Female Composers

Back in 2018 when I was awarded the AHRC networking grant for the Claimed from Stationers Hall network, I drew up a list of women composers from the Georgian era. There were more than one might have expected – perhaps they only composed a handful of pieces, in many cases, but nonetheless – they composed. You can find the list on a separate page on this blog, here. And you can read more about it in the blogpost I wrote in July 2018,

3. Mrs Bertram

This lady ran a girls’ school at St Leonard’s in St Andrews. This was NOT the famous and long-established private school that has long stood there, but an earlier enterprise. And Mrs Bertram and her daughters subsequently moved to Edinburgh, to the disappointment of parents of daughters in St Andrews!

- ‘Mrs Bertram’s Music Borrowing: Reading Between the Lines‘, 18 Sept 2017, Guest blogpost: EAERN (Eighteenth-Century Arts Education Research Network) https://eaern.wordpress.com/2017/09/18/mrs-bertrams-music-borrowing-reading-between-the-lines/

The photo portrays a Mrs Bertram of Edinburgh. Chronologically, she could well be ‘our’ Mrs Bertram, and a scholarly bent is suggested by the pile of books at her hand.

2. The Accomplished Ladies of Torloisk

I almost forgot about the musical Maclean-Clephane ladies of Torloisk, which is a stately home on the island of Mull. But how could I forget about them, considering I published a lengthy article about them some years ago?! Luckily, a book of letters by Sir Walter Scott crossed my library desk, and even though it didn’t contain those particular letters, this did remind me of his musical friends in Torloisk!

- Karen E. McAulay, ‘The Accomplished Ladies of Torloisk‘, International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, Vol. 44, No. 1 (June 2013), 57-78

1. Esteemed Academic introduces Composer Harriet Wainewright

Today, I’d like to introduce a woman composer who predates most of the individuals I’ve encountered. Professor James Porter applies his considerable intellect to produce this in-depth article:-

- ‘An English Composer and Her Opera: Harriet Wainewright’s Comàla (1792)’, Journal of Musicological Research Feb, 2021. Published online: 16 Feb 2021.

By and large, this book is aimed at book and publishing historians – it enumerates the contents of the Stationers’ Company Archive from 1554-1984, at Stationers’ Hall. The compiler, Robin Myers, was for a long time Honorary Archivist there. (She has the status of Liveryman at the Stationers’ Company.)

By and large, this book is aimed at book and publishing historians – it enumerates the contents of the Stationers’ Company Archive from 1554-1984, at Stationers’ Hall. The compiler, Robin Myers, was for a long time Honorary Archivist there. (She has the status of Liveryman at the Stationers’ Company.)

from 1821, the year of George IV’s coronation, and with a hole pierced in it by a previous owner so that it could be worn on a ribbon. As of course I already am!)

from 1821, the year of George IV’s coronation, and with a hole pierced in it by a previous owner so that it could be worn on a ribbon. As of course I already am!) I’m currently taking annual leave, and although I’m covertly pushing ahead with a couple of queries I’ve set myself, strictly speaking there should be a silence whilst I’m on holiday!

I’m currently taking annual leave, and although I’m covertly pushing ahead with a couple of queries I’ve set myself, strictly speaking there should be a silence whilst I’m on holiday!