The first and second Principals of the Glasgow Athenaeum School of Music weren’t actually in post very long. Allan Macbeth managed twelve years (1890-1902); then Edward Emanuel Harper, only two (1902-04). I’ve been researching them recently, and I do believe I’ve found out quite a bit more than has hitherto been known. But this post is not about their biographies and achievements – that’s for another time.

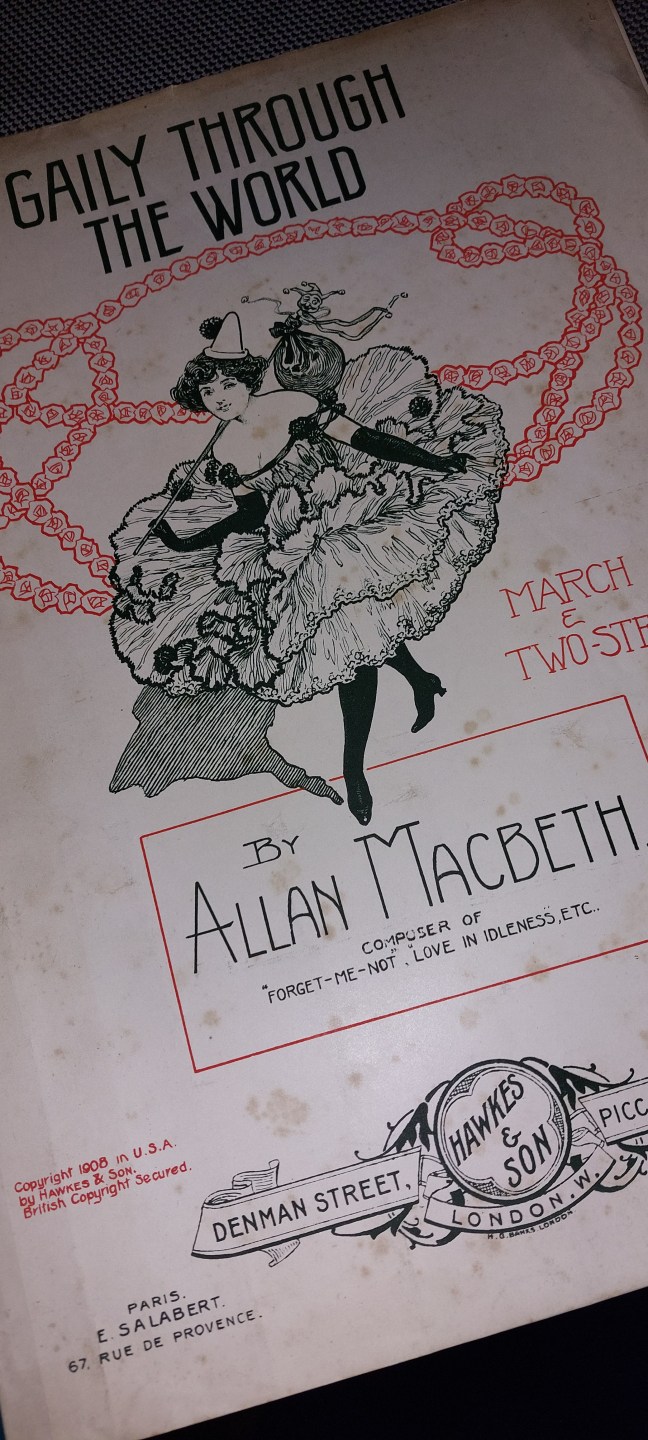

No, today is about practical music-making. Amongst a handful of compositions, Macbeth wrote a march and two-step, Gaily Through the World, which is actually very jaunty, and enjoyed quite a long life as a piece of band music. It’s not high art, but it does stand up as an effective piece of light music. It was published in 1908, two years before he died, by Hawkes. (Yes, the Hawkes that later went into partnership with Boosey in 1930.) That in itself is a mark of its respectability, if nothing else. The author of this YouTube posting says it was premiered at a Boosey Promenade Concert in 1896 – when Macbeth was in the middle of his Principalship.

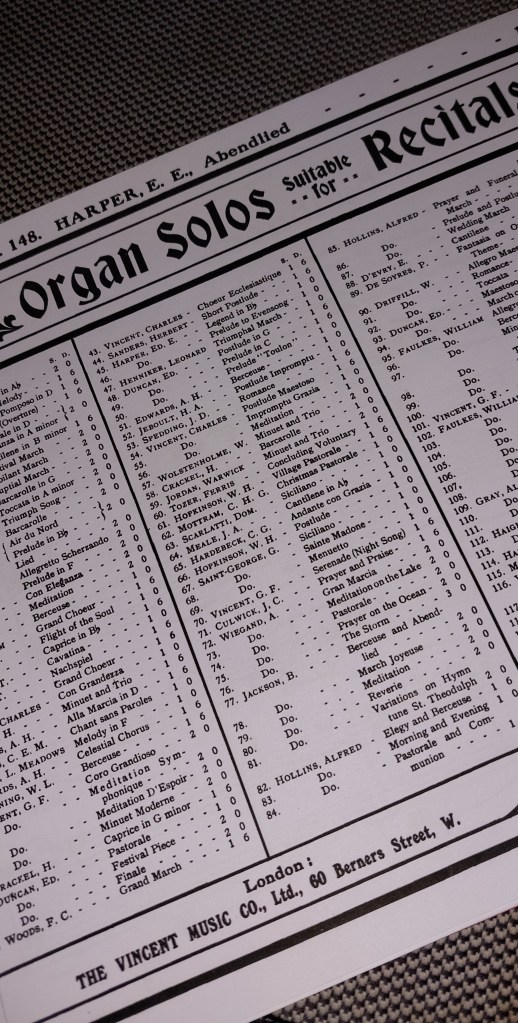

Harper seems to have had a larger output. Again, it was respectable but not remarkable. Nonetheless, I found a piece of organ music on IMSLP, this time published by Vincent Music in 1903, halfway through his own spell at the Athenaeum. (Vincent Music was the firm who would later publish James Woods and Learmont Drysdale’s Song Gems (Scots), which I’ve written about before. They were not as eminent as Boosey or Hawkes.) Abendlied is gentle and reflective, and appeared in an extensive series of ‘Organ Solos Suitable for Recitals’. It’s not hugely memorable, but it’s a nice enough piece for all that. Whilst Macbeth and Harper were both organists, each at several churches, I’ve formed the impression that being an organist occupied perhaps more of Harper’s career than it did of Macbeth’s, but this is really only a guess; moreover, Harper lived much longer than Macbeth and was only Principal of the Athenaeum for a couple of years. He obviously occupied himself in other ways for the rest of his career, and I have quite a list of the churches where he ‘presided’ at the organ.

Anyway, I digress. I played Abendlied before morning worship this morning. (No-one knew it was an ‘Abend Lied’, after all!) It could well have been played by Harper, just a couple of miles up the road, when he was organist at Kilbarchan.

But I saved Macbeth’s Gaily Through the World for my outgoing voluntary – and it did get noticed! It fitted the organ so well that I wondered if he had ever tried it at the organ himself – though maybe he might not have considered it serious enough for late Victorian Presbyterians …