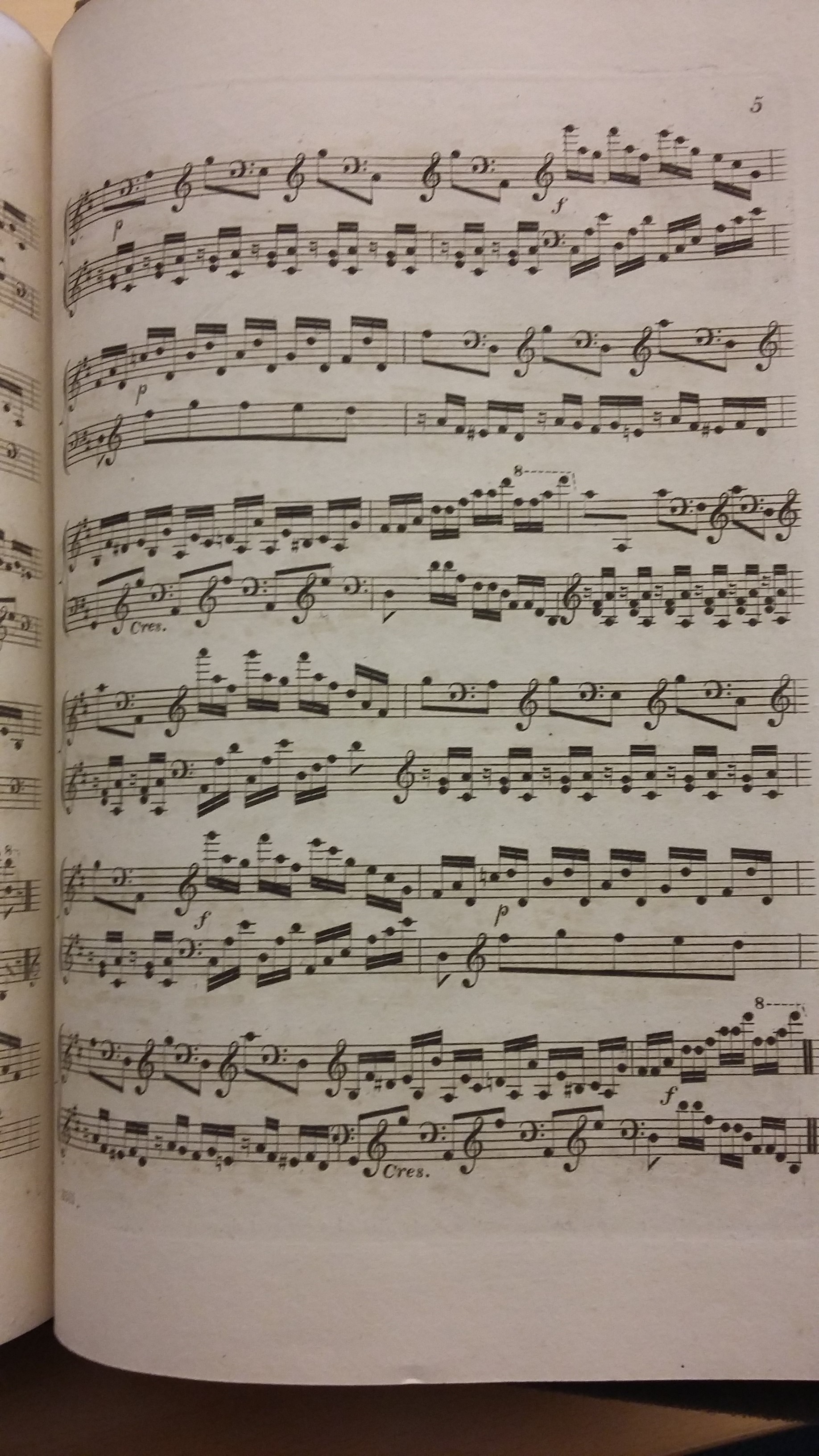

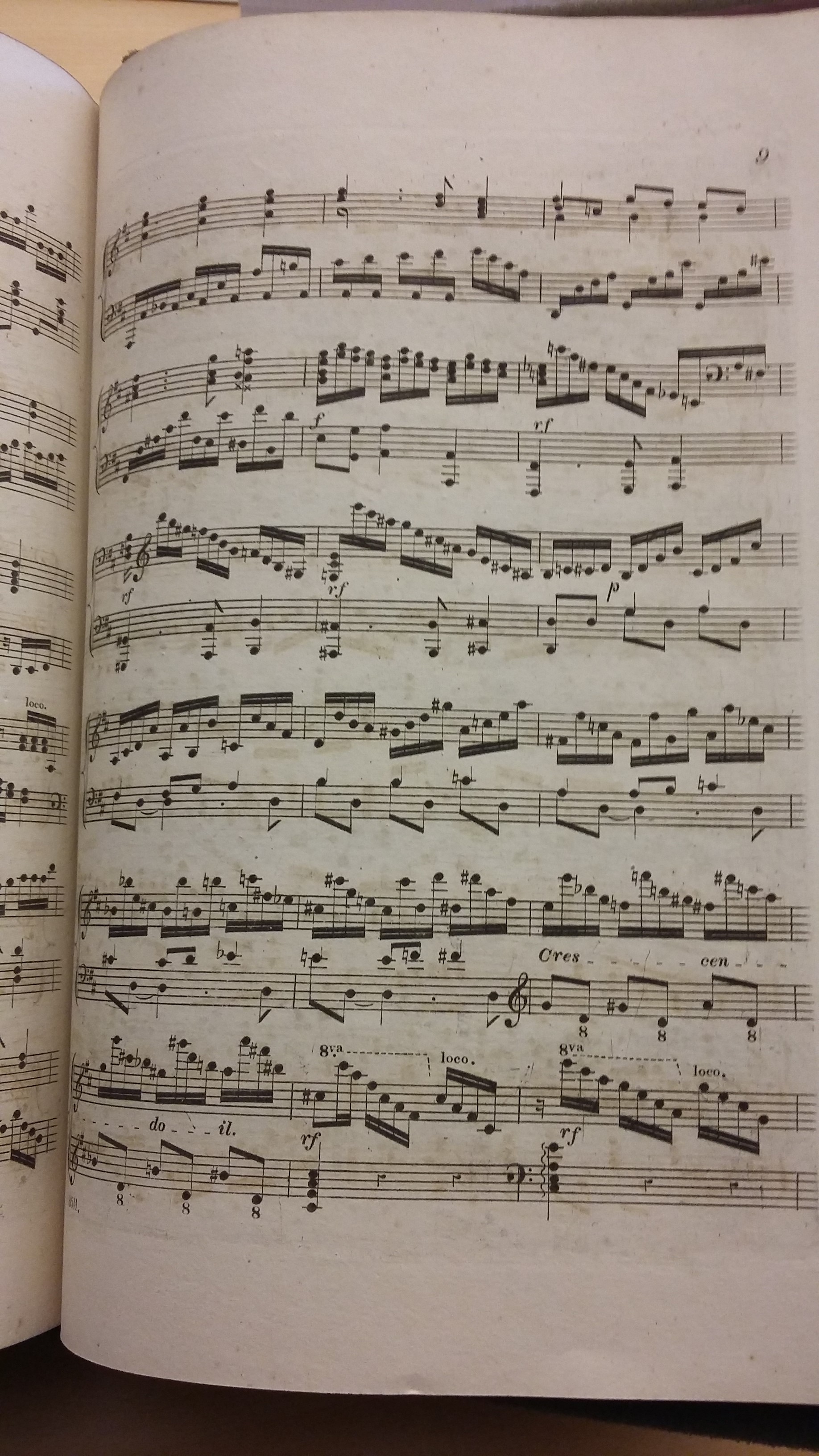

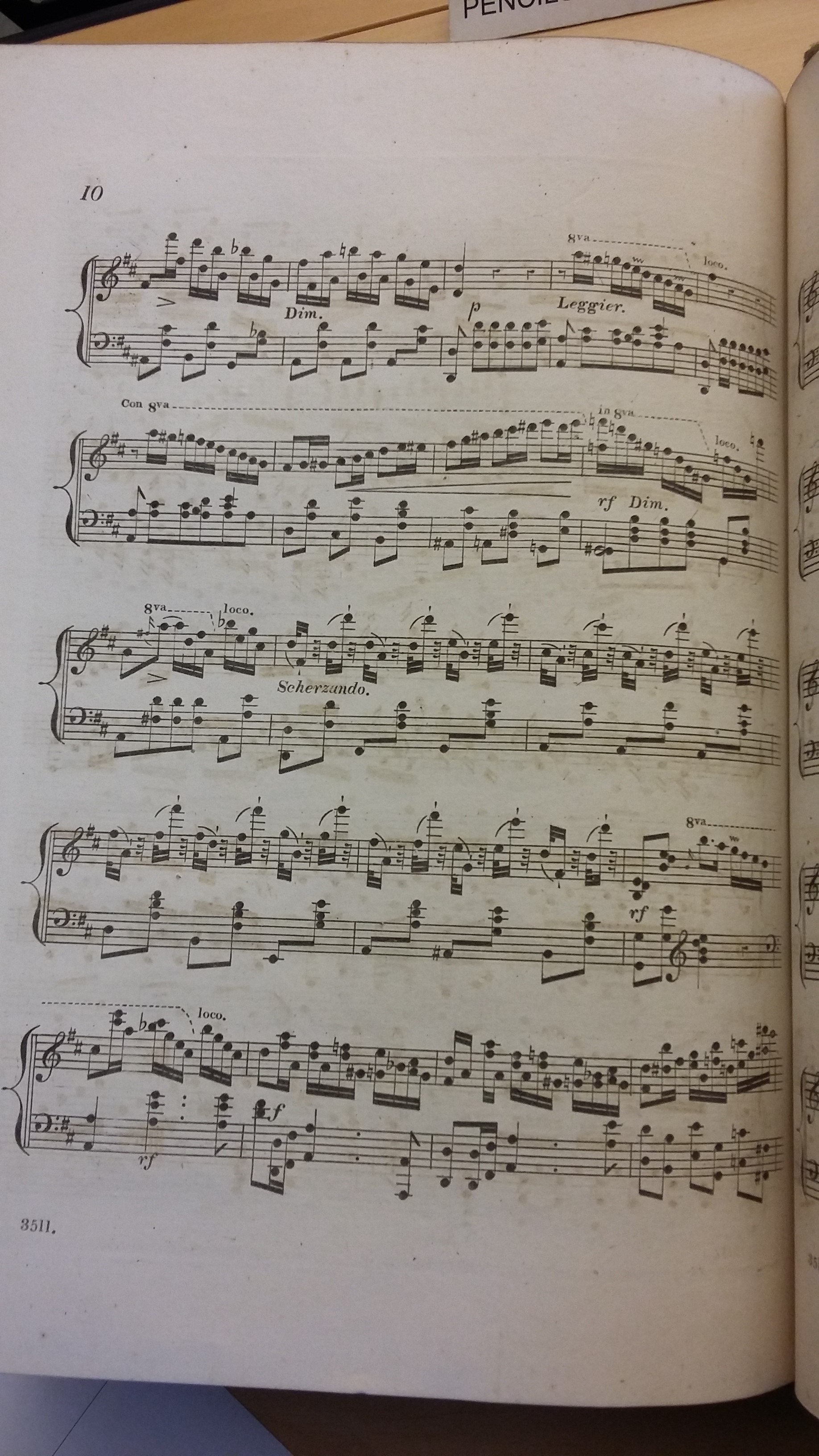

Reaching the end of my recent cataloguing project – the gift of a number of books of old Scottish music – I must confess I left what looked like the most miscellaneous, worn, unbound pieces until last. Late on Friday afternoon, I had observed that one such piece had a pencil note at the head – ‘Music for The Gentle Shepherd, Foulis edition, 1788’. Now, this is a famous ballad opera by Allan Ramsay. It was so popular that my colleague Brianna Robertson-Kirkland writes that there were 86 editions of The Gentle Shepherd, 66 of them the ballad opera. Initially, the songs only indicated the name of the tune to use, and different editions have more or less songs. The 1788 edition contains a full vocal score of the songs, and that’s what we’ve got. My guess is that the last owner bought the 18 pages which someone had previously separated from the back of the larger original volume.

I haven’t made a study of it myself, but I do recognise the opera and its songs as very significant in the history of Scottish music – and this edition has particular importance. So, if this gathering of pages was so important, it would benefit from a decent catalogue entry.

The pages are numbered 1-18. With no title-page, still less a cover, to give me further clues, it wasn’t a task for 4.30 on a Friday afternoon, but it very definitely was one for a Monday morning.

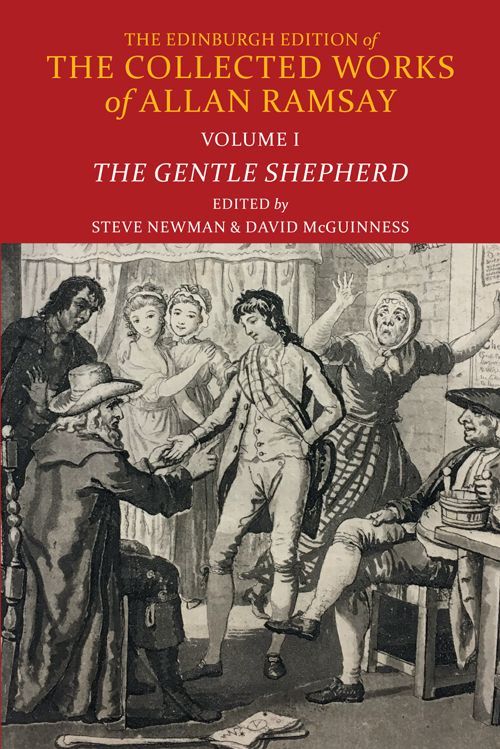

A bit of digging around soon found me another library’s catalogue record of Ramsay’s ballad opera in that very edition – a particularly significant edition, because it’s the most lavish, quite apart from having the complete vocal score section. RCS lecturer Brianna Robertson-Kirkland has researched the work in detail and written an article about it, which is on one of her class reading-lists. Dr David McGuinness, with whom I worked on the HMS.Scot AHRC-funded project a few years ago, has also recently published a book about it, with Steve Newman.

But the catalogue record didn’t exactly fit my purpose, because what I had in my hand was the appendix at the end of the book, containing all the songs. We didn’t have the text of the ballad opera at all.

No problem – I downloaded the catalogue record and adapted it to reflect what we did have. I made sure the words ‘Scottish songs’ appeared in the catalogue record, and I indexed every one of those songs. The appendix is only eighteen pages long – it wasn’t that arduous a task. I’m really happy that we’ve been given this, because – even though it’s fragile and will have to be handled with extreme care – it means the students will now be able to see the music that Brianna has written about, and lectures about. (It still needs a nice stout card folder, and a secure storage space – but they’ll be sorted out soon.)

Informed Cataloguing

There’s one strange thing, though. It appears no other cataloguer has catalogued each song in The Gentle Shepherd – not in Jisc Library Hub, at any rate. Well, although we at RCS might not have the whole magnificent text, a title page or a cover, we HAVE now got a catalogue record which indexes all the songs. Hooray!

Contents:-

- The wawking of the fauld (1st line: My Peggy is a young thing)

- Fy gar rub her o’er wi’ strae (1st line: Dear Roger, if your Jenny geck)

- Polwart on the Green (1st line: The dorty will repent)

- O dear mother, what shall I do (1st line; O dear Peggy, love’s beguiling)

- How can I be sad on my wedding day (1st line: How shall I be sad when a husband I hae?)

- Nansy’s to the green-wood gane (1st line: I yield, dear lassie)

- Cauld kail in Aberdeen (1st Line : Cauld be the rebels cast)

- Mucking o’ Geordie’s byre (1st line: The laird, wha in riches)

- Carle, an’ the king come (1st line: Peggy, now the king’s come)

- The yellow-hair’d laddie (1st line: When first my dear ladie gade to the green hill)

- By the delicious warmness of thy mouth

- Happy Clown (1st line: Hid from himself)

- Leith Wynd (1st line: Were I assur’d)

- O’er Bogie (1st line: Weel, I agree ye’re sure o’ me)

- Kirk wad let me be (1st line: Duty, and part of reason)

- Woe’s my heart that we shou’d sunder (1st line: Speak on, speak thus)

- Tweed Side (1st line: When hope was quite sunk in despair)

- Bush aboon Traquair (1st line: At setting day and rising morn)

- The bonny grey-ey’d morn

- Corn-Riggs (1st line: My Patie is a lover gay)

I struggled to explain to my family just how gratifying I find this. But I think it’s really important not only that Brianna’s students can see which songs are in Foulis’s edition of The Gentle Shepherd, but also, anyone looking for one of those song titles will be able to see that it was one of the songs used in the famous ballad opera.

- Our new acquisition:- The Gentle Shepherd : a pastoral comedy . Music appendix only

- Brianna Robertson-Kirkland, ‘Mapping changes to the songs in The Gentle Shepherd, 1725-1788‘, Studies in Scottish Literature (2020), vol.46, issue 2, pp.103–126

- The Gentle Shepherd / Allan Ramsay ; edited by Steve Newman, David McGuinness.

As a matter of interest, we do also have some items going back to the era when Cedric Thorpe Davie put on a performance of the opera. Anyone checking our catalogue will spot those too!

- Davie, Cedric Thorpe, handwritten draft programme for performance at Edinburgh International Festival

- The Gentle Shepherd : a pastoral by Allan Ramsay (1685-1758) ; music by Cedric Thorpe Davie

- The Gentle Shepherd: a pastoral comedy / by Allan Ramsay ; abridged and adapted for performance at Edinburgh International Festival by Robert Kemp [bound photocopy, 47 p.]