What do you know? I’m delighted to discover that my article is February Article of the Month in vol.56 of the RMA Research Chronicle!

What do you know? I’m delighted to discover that my article is February Article of the Month in vol.56 of the RMA Research Chronicle!

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned that my RMA Research Chronicle article was now available online as open access. Today, it’s actually in the published issue. Receiving this email is a great start to the day:-

“your article, ‘Women Pursuing Musical Careers: Finding Opportunities in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Scottish Music Publishing Circles’, has now been published in Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle! You can view your article at https://doi.org/10.1017/rrc.2025.10009 “

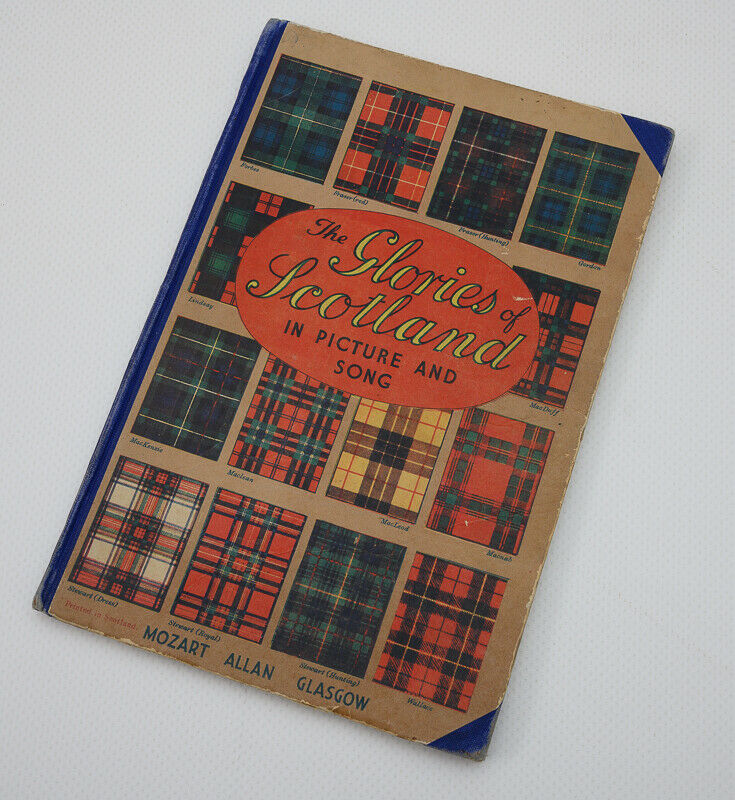

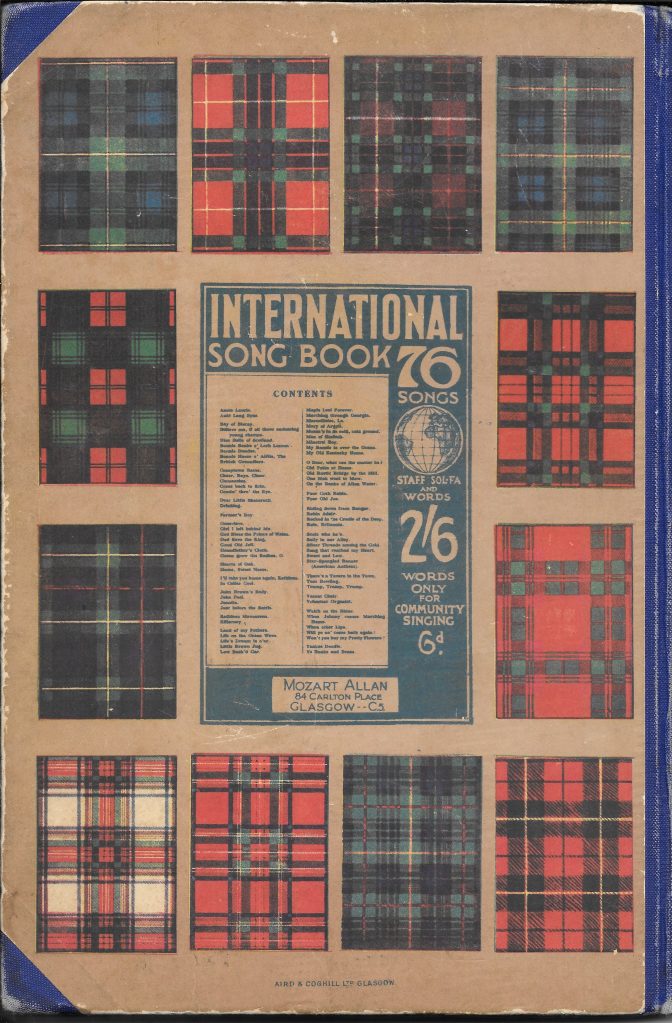

What’s this?, I hear you ask. Why would a musicologist write about tourism? Well, it’s like this: one of the song book titles that I explored in last year’s monograph, The Glories of Scotland, really deserved more space than I could give it in a monograph devoted to a nation’s music publishing. However, the opportunity came up to contribute a chapter to a Peter Lang Publication, Print and Tourism: Travel-Related Publications from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century, edited by Catherine Armstrong and Elaine Jackson.

Today, I received the final proofs, which means that the book itself can’t be very far away. I really enjoyed writing this chapter – you could say that it’s decidedly more about publishing history, and tourism, than conventional musicology – and I really look forward to it actually being published.

My chapter (19 pages):-

‘The Glories of Scotland in Picture and Song’: Jumping on the Festival of Britain Bandwagon?’

Published online today, 12 January 2026, in the RMA (Royal Musical Association) Research Chronicle, by Cambridge University Press, on Open Access:- click here.

Writing this article was enormously fulfilling. I had encountered these ladies whilst researching my latest monograph, and I became convinced that they deserved profiling in their own right, and not merely as bit-parts in the larger picture occupied by their husbands, fathers and brothers.

The kernel of the abstract states that, ‘This article focuses on a group of Scottish women who did not make their names solely as art music composers or stellar performers, and for whom piano teaching was only part of their musical work. Four were related to the Scottish music publishers Mozart Allan, James Kerr, and the Logan brothers; the fifth published with Allan and Kerr, and also self-published.’

And all had fulfilling portfolio musical careers. Read on, and I’m sure you’ll agree!

Remembering my fruitful walk on 3 January 2023, I looked outside today – yes, the third of January again – saw the sun shining (athough the temperature was literally freezing out there), and decided to go on another research-and-exercise outing. What could possibly go wrong?

I’ve been exploring the story of a Victorian Glasgow music professor, so I headed for St George’s Cross by subway, to see a former church where he had once been organist. He had started his tenure in an earlier building, which was burned down in a fire, but a new one was built in a mere two years, so he must have resumed duties at that point. I already knew that, as with organist Maggie Thomson’s Paisley church, this Glasgow church had likewise now been converted into rather classy flats.

Unperturbed, I headed next to the Mitchell Library, and up to the fourth floor where the old music card catalogue lives; it has never been digitized. This eminent individual certainly composed enough, but mostly in a light-music vein, and not published by any of Glasgow’s bigger music publishers. However, I was still surprised to discover that he is completely unrepresented in the card catalogue.

To drown my sorrows, I headed next to a celebrated Turkish coffee shop in Berkeley Street. (The premises had once been a club for Glasgow musicians, and our hero had been included in a song-book that they sponsored; clearly I needed to have a coffee there in his honour.) Foiled again! There was a queue out to the pavement, just to get inside the cafe. Back I went to the Mitchell Library cafe, to get my coffee more quickly!

It was still bright and sunny outside, so my next port-of-call was India Street (on the opposite side of the M8, near Charing Cross station). This had been both of professional significance and latterly home to our hero, and although I knew modern developments had taken place, I still hoped that I might be able to walk the length of the street. Thwarted! Scottish Power sits squatly and solidly across the line of the road, and pedestrian access is blocked by ongoing building works before you even get to it.

I could have headed into the city centre to gaze at the Athenaeum, but I’ve passed it hundreds of times, and there are plenty of pictures on the web – it wouldn’t have felt like much of a discovery. Sighing – for the mere glimpse of a road sign at the wrong end of India Street had not exactly thrilled me – I headed for the bus home.

But fate had one more twist for me: whilst I was looking on the travel app to find out when the next bus was due …

… the next bus sailed past my stop.

I decided that maybe walking briskly to the Subway would be quicker than waiting for another bus. At least the Subway dates from the era when our hero was in his prime and doing well.

‘How did you get on?’, I was asked, when I got back home. I was forced to admit that, apart from St-George’s-in-the-Fields, I had really seen virtually nothing.

On the plus side, my FitBit is as happy as Larry. Finally, it said, she has realised that Christmas is over, and it’s time for the healthy living to resume!

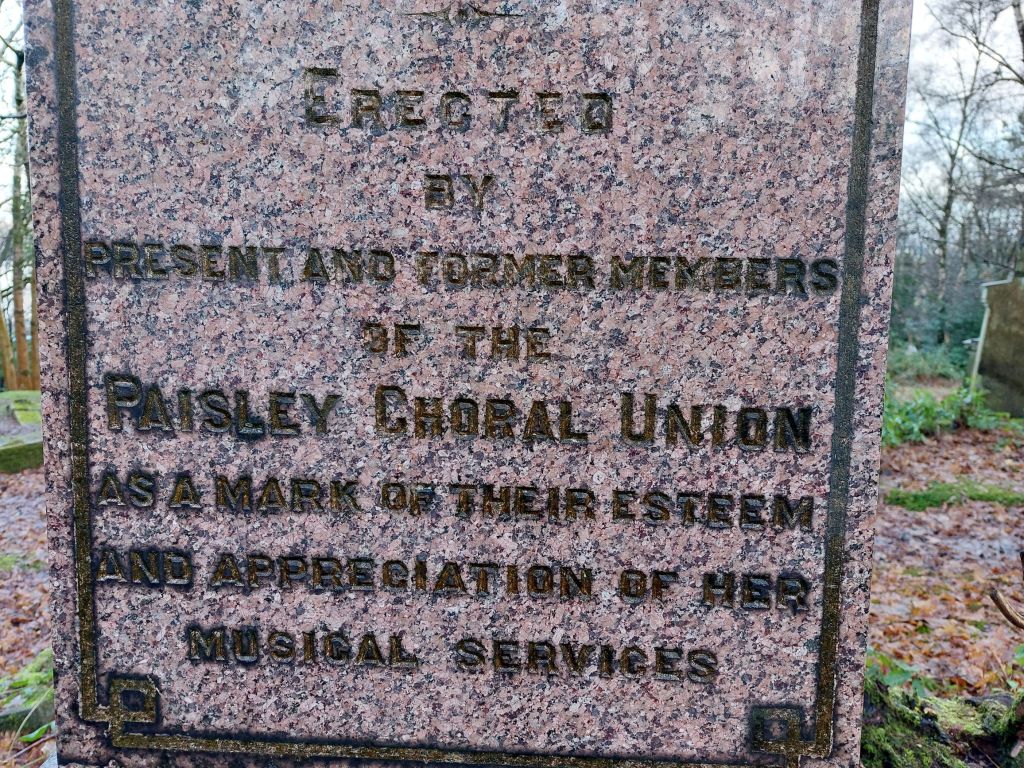

On this day, 3 January 2023, I went in search of this late Victorian lady’s grave in a Paisley cemetery. She’d been a noted local celebrity, reputed to be the best accompanist in the town. Sadly, she lost her mind to grief after her mother’s death, and died in an asylum.

The gravestone was extravagantly impressive – even though the obelisk has sadly been taken down for health and safety reasons.

Nonetheless, her story is interesting and moving, and her connection with Paisley publisher Parlane ensured her a mention in my book.

I also wrote a more detailed biographical article for the Glasgow Society of Organists, and reproduced it in this blog.

Postscript. I went on another 3rd January expedition this afternoon. More of that another day!

So, 202 years ago today, William Motherwell received Smith’s letter with accompanying draft preface. He would attend to the Scotish Minstrel Preface, he assured Smith. But …

… it would take him a week to get over his Hogmanay celebrations.

However much had he celebrated? Too hungover to do the task, but capable of writing back immediately?

Musician Robert Archibald Smith edited six volumes of The Scotish Minstrel (yes, Scotish) between 1820-1824. It was a project coordinated by Lady Carolina Nairne and her committee of ladies.

On this day, 1 January 1824, Smith wrote to William Motherwell, who was supposed to be writing a preface for them. To speed things up, the ladies had written text that Motherwell was now asked to edit as he saw fit.

Motherwell did reply by return of post, but not with the edited preface. However, that’s a story for tomorrow!

Image of William Motherwell, from National Galleries of Scotland

If you’ve made any kind of study of Scottish songs and fiddle tunes, you’ll know that collector Andrew Wighton (1804-1866) bequeathed his fantastic music collection to the City of Dundee. As the Friends of Wighton website says, ‘Andrew J Wighton (1804-1866) was a merchant in Dundee. He built a music collection which is now of international renown and importance. After his death, his Trustees donated the music to the then Free Library in Dundee’. The Friends of Wighton is a charity which exists to promote the collection and the performance and study of Scottish music. I’m proud to be the honorary librarian.

On 31 December 1855, Wighton’s Aberdonian friend James Davie wrote to him observing that Wighton must, by now, have,

… the finest collection of old [Scottish] music in the three kingdoms.

You only have to look at the online catalogue today to see that Davie was perfectly accurate in his observation!

There are a few places where my in-laws’ history and my own research findings overlap. Glasgow is one of them, and Greenock is another. I know the stories of three mid-nineteenth century Greenock boys, all with family connections to shipping on the River Clyde: I encountered two of them whilst researching Scottish music publishers, but the other one is indirectly linked to me by marriage.

Allan Macbeth was born in Greenock in 1856 to an eminent artist. After the family had moved to Edinburgh, he had two spells studying music in Germany, but he did return to Scotland. He married the daughter of a Greenock builder, ships carpenter, timber-merchant and saw-miller. Between 1880-7, he conducted Glasgow Choral Union.

Between 1890 -1902, he was Principal of Glasgow’s Athenaeum School of Music, building it up to a size barely imagined by the early directors. In 1902, he left to open his own Glasgow College of Music in India Street, taking umbrage after the Athenaeum directors decided they didn’t want a Principal who also taught classes. His own college appears to have died with him when he died in 1910.

Technically capable, in terms of musicianship, he wrote a quantity of lightweight music, eg his Forget me Not intermezzo and Love in Idleness serenata, both of which were subsequently re-arranged for different instrumentations, shortly after his death. Barely any of his music was published in Scotland – It was almost all published in England by a mixture of big and very small names.

Macbeth was one of the arrangers of James Wood and Learmont Drysdale’s Song Gems (Scots) Dunedin Collection, published in 1908 both in London and Boston, Massachusetts. Indeed, my own copy came from Boston, though there had also been an Edinburgh distributor. His Scottish song arrangements were typically late Romantic in style. The collection was aimed at a musically and culturally educated middling class, knowledgeable about Scottish poetry of earlier times. For example, his setting of Walter Scott’s ‘The Maid of Neidpath’ was set to an earlier tune by Natale Corri – hardly of Scottish origin! – with lush harmonies. I wrote about the collection in my A Social History of Amateur Music Making and Scottish National Identity (Routledge, 2025).

Macbeth’s son, Allan Ramsay Macbeth, briefly attended Glasgow School of Art (GSA) as an architectural apprentice before leaving to become an actor, and one of his cousins, Ann Macbeth, became head of embroidery there.

Twelve years after Macbeth’s birth, a second musical boy was born in 1868, this time to a wealthy ship-owning family in Greenock. The family firm later went bankrupt, but not before James MacCunn had benefited from a composition scholarship to the newly established Royal College of Music in London at a very young age. Like Macbeth, he left Scotland to further his musical education. He styled himself Hamish to suit his ostentatiously Scottish persona, and spent the rest of his life in England, determined to live in the style to which he had become accustomed. His compositions were on a decidedly larger and more ambitious scale than Macbeth’s, but he perhaps didn’t live up to his early adult promise, and his insistence on flaunting his Celtic origins may ultimately have gone against him. He too gets a mention towards the end of my Social History of Amateur Music Making.

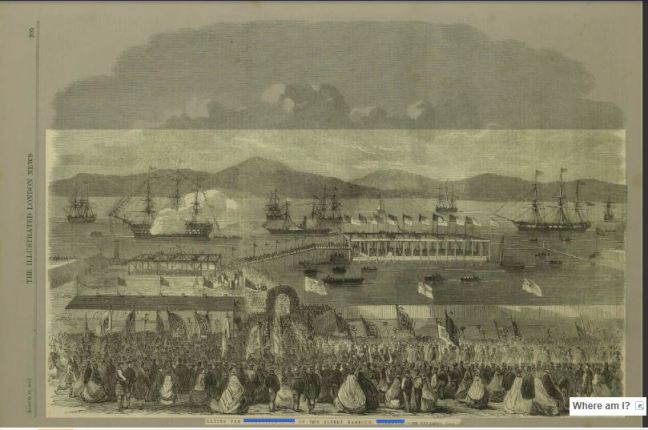

Also in the 1860s, my grandfather-in-law was born in Greenock to a much lowlier family, in 1866. (If you’re trying to calculate how my grandfather-in-law was born 159 years ago, shall we just say that age-gaps account for a lot.) This baby was the second Hugh born in the family, after the first one died of teething. Life wasn’t easy for the illiterate working-class poor; this family had already moved from Ballymoney on the north coast of Ireland, in pursuit of work on the Clyde. His father Alexander worked in the shipyards as a hammerman until his untimely demise one Hogmanay. Last seen on 31 December 1873, Alexander drowned in Albert Harbour and was found a month later. Did he jump, or was he pushed? We’ll never know!

My husband’s grandfather Hugh was later to move his young family to Tyneside in pursuit of work as a ship’s carpenter. Family mythology has various spellings of our name – but since our immigrant Irish McAulays were illiterate, there is no correct spelling. It was spelled however the registrar, or newspaper editor, chose to spell it. There was an embroidered family tale about my Great-Grandfather-in-Law, erasing the embarrassing Hogmanay drowning – and another story about Grandpa-in-Law’s move to Tyneside after a dispute with his foreman (which has every chance of being equally inaccurate).

I can’t help comparing how different were the lives of the two promising young musicians, and the Clydeside then Tyneside shipyard worker who was to thrive on tonic sol-fa, and whose adult family were to make up at least half of their Presbyterian church choir!

Image: Photo of the laying of the foundation stone, Albert Harbour Greenock, from the Illustrated London News 23 August 1862, p. 9 (British Newspaper Archive)

I just remembered a tiny detail about Sir John Macgregor Murray that didn’t make it into my recent Folk Music Journal article!

213 years ago today, we’d have found him at his writing desk, Christmas Day or not. He was writing to Lewis Gordon about,

‘inspecting the Materials collected by the Society.’

This was in connection with the Gaelic dictionary project. In fairness, they didn’t make a big splash of Christmas then. At least he was doing something he enjoyed!

***

‘Sir John Macgregor Murray: Preserver of Highland Culture, Music and Song’. Folk Music Journal vol. 13 no.1, pp.50-63.