What do you know? I’m delighted to discover that my article is February Article of the Month in vol.56 of the RMA Research Chronicle!

What do you know? I’m delighted to discover that my article is February Article of the Month in vol.56 of the RMA Research Chronicle!

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned that my RMA Research Chronicle article was now available online as open access. Today, it’s actually in the published issue. Receiving this email is a great start to the day:-

“your article, ‘Women Pursuing Musical Careers: Finding Opportunities in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Scottish Music Publishing Circles’, has now been published in Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle! You can view your article at https://doi.org/10.1017/rrc.2025.10009 “

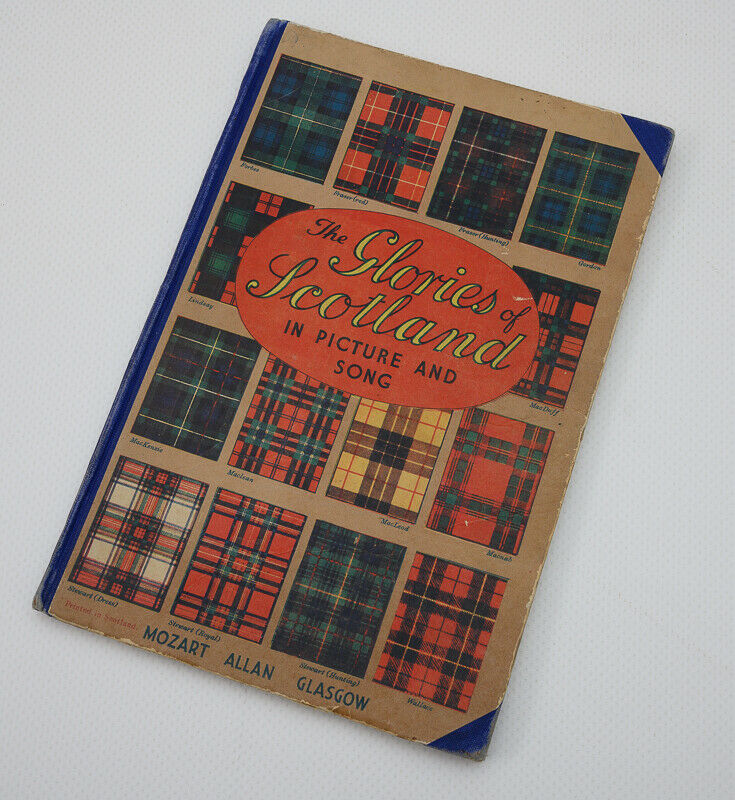

What’s this?, I hear you ask. Why would a musicologist write about tourism? Well, it’s like this: one of the song book titles that I explored in last year’s monograph, The Glories of Scotland, really deserved more space than I could give it in a monograph devoted to a nation’s music publishing. However, the opportunity came up to contribute a chapter to a Peter Lang Publication, Print and Tourism: Travel-Related Publications from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century, edited by Catherine Armstrong and Elaine Jackson.

Today, I received the final proofs, which means that the book itself can’t be very far away. I really enjoyed writing this chapter – you could say that it’s decidedly more about publishing history, and tourism, than conventional musicology – and I really look forward to it actually being published.

My chapter (19 pages):-

‘The Glories of Scotland in Picture and Song’: Jumping on the Festival of Britain Bandwagon?’

Published online today, 12 January 2026, in the RMA (Royal Musical Association) Research Chronicle, by Cambridge University Press, on Open Access:- click here.

Writing this article was enormously fulfilling. I had encountered these ladies whilst researching my latest monograph, and I became convinced that they deserved profiling in their own right, and not merely as bit-parts in the larger picture occupied by their husbands, fathers and brothers.

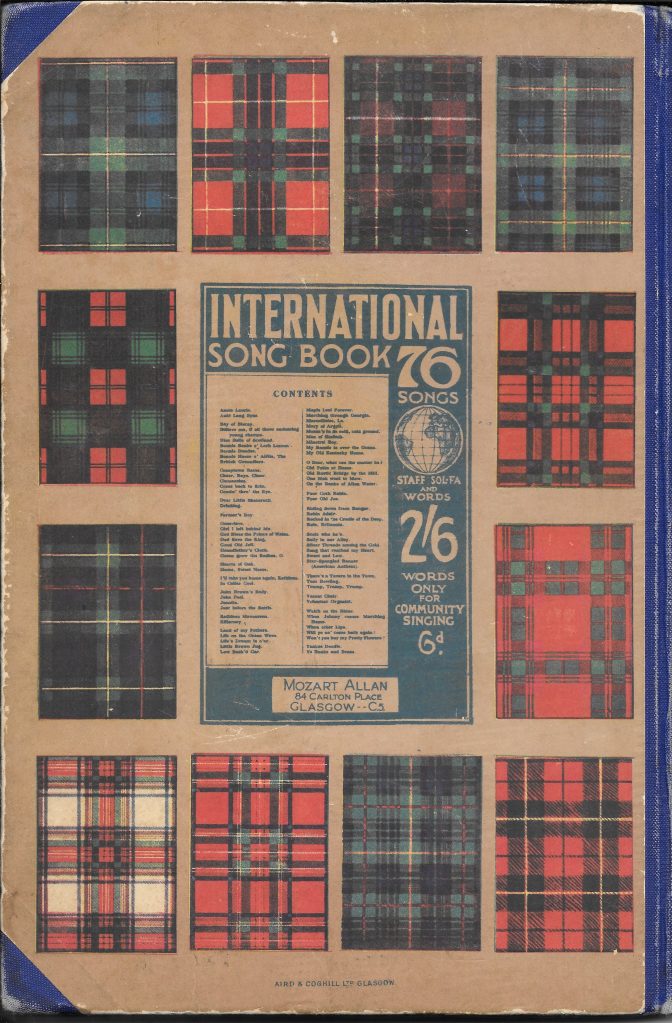

The kernel of the abstract states that, ‘This article focuses on a group of Scottish women who did not make their names solely as art music composers or stellar performers, and for whom piano teaching was only part of their musical work. Four were related to the Scottish music publishers Mozart Allan, James Kerr, and the Logan brothers; the fifth published with Allan and Kerr, and also self-published.’

And all had fulfilling portfolio musical careers. Read on, and I’m sure you’ll agree!

Remembering my fruitful walk on 3 January 2023, I looked outside today – yes, the third of January again – saw the sun shining (athough the temperature was literally freezing out there), and decided to go on another research-and-exercise outing. What could possibly go wrong?

I’ve been exploring the story of a Victorian Glasgow music professor, so I headed for St George’s Cross by subway, to see a former church where he had once been organist. He had started his tenure in an earlier building, which was burned down in a fire, but a new one was built in a mere two years, so he must have resumed duties at that point. I already knew that, as with organist Maggie Thomson’s Paisley church, this Glasgow church had likewise now been converted into rather classy flats.

Unperturbed, I headed next to the Mitchell Library, and up to the fourth floor where the old music card catalogue lives; it has never been digitized. This eminent individual certainly composed enough, but mostly in a light-music vein, and not published by any of Glasgow’s bigger music publishers. However, I was still surprised to discover that he is completely unrepresented in the card catalogue.

To drown my sorrows, I headed next to a celebrated Turkish coffee shop in Berkeley Street. (The premises had once been a club for Glasgow musicians, and our hero had been included in a song-book that they sponsored; clearly I needed to have a coffee there in his honour.) Foiled again! There was a queue out to the pavement, just to get inside the cafe. Back I went to the Mitchell Library cafe, to get my coffee more quickly!

It was still bright and sunny outside, so my next port-of-call was India Street (on the opposite side of the M8, near Charing Cross station). This had been both of professional significance and latterly home to our hero, and although I knew modern developments had taken place, I still hoped that I might be able to walk the length of the street. Thwarted! Scottish Power sits squatly and solidly across the line of the road, and pedestrian access is blocked by ongoing building works before you even get to it.

I could have headed into the city centre to gaze at the Athenaeum, but I’ve passed it hundreds of times, and there are plenty of pictures on the web – it wouldn’t have felt like much of a discovery. Sighing – for the mere glimpse of a road sign at the wrong end of India Street had not exactly thrilled me – I headed for the bus home.

But fate had one more twist for me: whilst I was looking on the travel app to find out when the next bus was due …

… the next bus sailed past my stop.

I decided that maybe walking briskly to the Subway would be quicker than waiting for another bus. At least the Subway dates from the era when our hero was in his prime and doing well.

‘How did you get on?’, I was asked, when I got back home. I was forced to admit that, apart from St-George’s-in-the-Fields, I had really seen virtually nothing.

On the plus side, my FitBit is as happy as Larry. Finally, it said, she has realised that Christmas is over, and it’s time for the healthy living to resume!

Anyone looking at my publication record is soon going to be mightily confused. The article about Sir John Macgregor Murray concerns a Highlander who lived from 1745-1822. I wrote it at a time when I was still researching Scottish music collecting and publishing in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-centuries.

Today, I received the final proofs for the next extensive article. This time, it’s about Scotswomen with portfolio music careers in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. (Two of them were of English parentage, but let’s not quibble!) A spin-off from my latest book, in the sense that I turned my focus onto a number of individuals who had hung around in the shadows of the book, this article extends over some 22 pages, and luckily there wasn’t a great deal needing changing in the proofs. But the instructions for using the proofing system extended over 49 pages, and there was also a ten-step quick tour of the process. I nearly had a fit at the sight of the former, but the latter told me nearly all I needed to know. Job done.

There are still more articles in the pipeline; I’ll flag them up as they come along! Meanwhile, there’s the small matter of Christmas requiring my attention during the semi-retired part of my existence, not to mention the continued tidying up of our poor scarred, rewired residence! But first, I need stamps …

Image: Glasgow Athenaeum, forerunner of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (Wikimedia Commons) – where two of ‘my’ musical ladies received their advanced musical training.

It’s not as though I’m unaccustomed to what I’ve been doing in odd moments for the past few days. Over the years, I’ve opened dozens, indeed hundreds of old song books and other music publications, trying to read their prefaces, annotations and harmonic arrangements as though I were a contemporary musician rather than a 21st century musicologist. Looking at music educational materials is likewise not new to me.

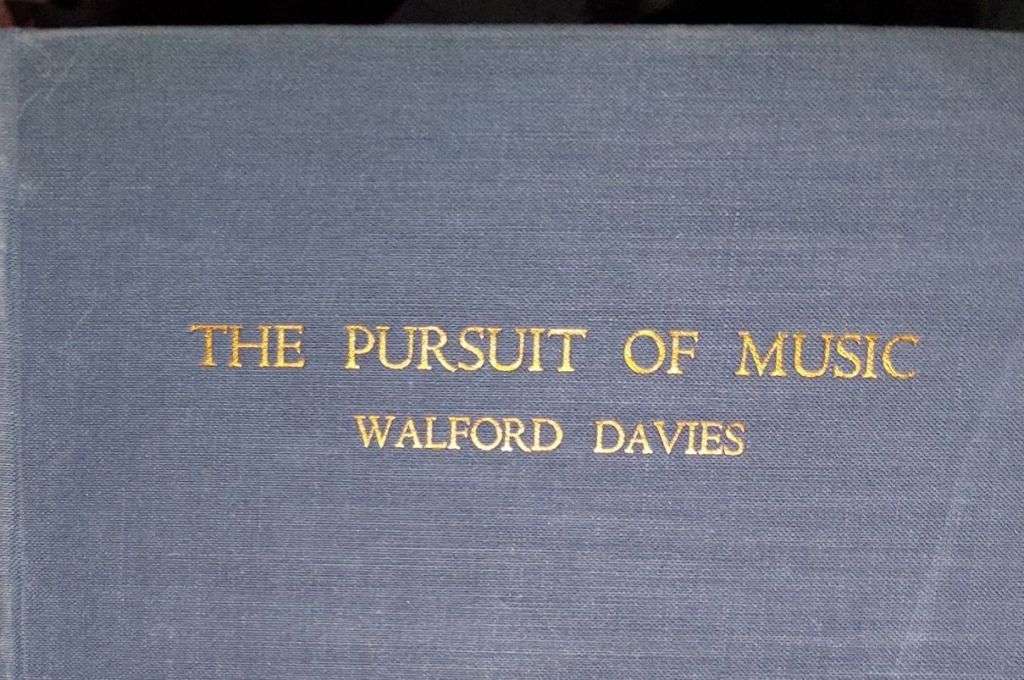

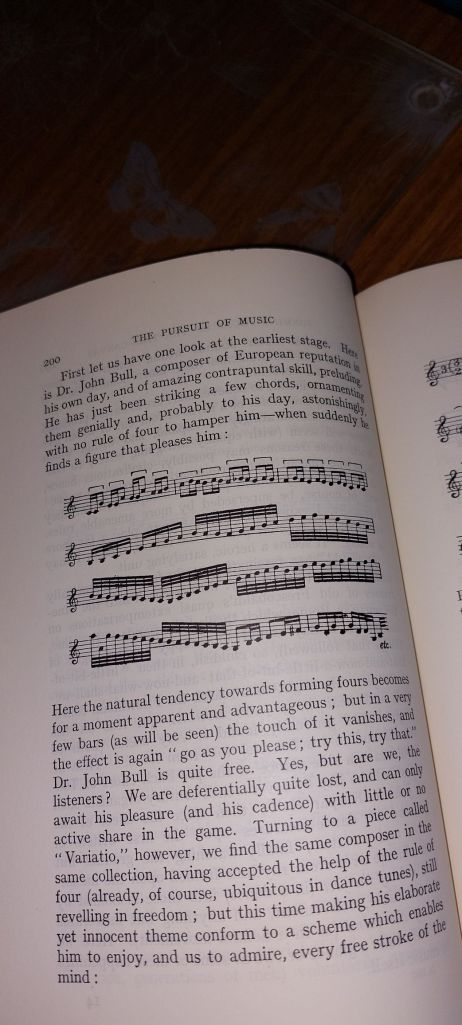

He was the first music professor at the University of Aberystwyth, but he was also hugely popular in the 1920s-30s through his broadcasting work – fully exploiting the new technology of wireless and gramophone for educational purposes, and to share his love of music with the ordinary layman wishing to know more about all they could now listen to. This book was written after he’d mostly, but not entirely retired.

It wasn’t exactly what I expected! If I thought he would write about what made the Pastoral Symphony pastoral, or Die Moldau describe a river’s journey, I rapidly had to change my expectations.

His audience was apparently not just the average layperson, but also young people in their late teens, not long out of school. If the reader didn’t play the piano, they were urged to get a friend to play the examples for them. (Considering the book is over 400 pages, you can imagine how long they’d be – erm – captive!)

And this was aesthetics, 90 years ago. I struggled to get into the mindset of a layperson wanting to know what music (classical, in the main) was ‘about’, without knowing what a chord was, or realising that music occupies time more than space. Would I have benefited from that knowledge? Would being told in general terms what the harmonic series was, have helped me appreciate the movements of a string quartet? Or Holst’s The Planets?

It wasn’t about musical styles over the years. I didn’t read it cover to cover, but neither did it appear to explain musical form and structure as I would have expected.

Davies’ biographer, H. C. Colles, did comment that it was a mystifying book, and suffered from the fact that the author’s strengths were in friendly and persuasive spoken, not written communication.

I’ve only heard snatches of his spoken commentary, so I can’t really say. Apart from which, Colles made an observation about Davies’ written style. Colles was a contemporary authority who knew Davies personally – and he may have been picking his own words carefully, so as not to cause offence. My own disquiet is more a matter of content: was it what his avowed audience needed, to start ‘understanding music’?

I think I have been mystified enough.

I wonder what the Nelson editors made of this book by one of the great names of their age? They published it, and I think regarded him as a catch, but what did they actually think?!

And did the layperson, assuming they got through the 400+ pages, lay it down with a contented sigh, feeling that now they understood music?

I have a tiny cutting on my pinboard, which reminds me that,

Many of life’s failures are people who did not realise how close to success they were when they gave up. – Thomas Edison

It’s painfully true in life, but it’s also particularly pertinent in archival research!

Yesterday, I was trawling the most random of files. To be fair, a couple were even labelled ‘Miscellaneous’ in the handlist. However, they date from an era I need to know more about, so I was going to look at them! I entered a rabbit warren of curiosities.

By 4 pm, I had a splitting headache, and was quickly flicking through pages as fast as I dared – the paper was fragile, and I still didn’t want to miss something important.

Why not admit defeat and give up on this box file?, I mused. There was nothing relevant in it. Interesting, but irrelevant.

Then I saw it. A beautiful little note from no less than British composer Peter Warlock! In the grand scheme of things, it’s not of huge significance – it’s just an apology for his delayed response, and a request to correct a small detail before publication – but it does confirm the editor’s identity (something I hadn’t yet managed to do, apart from finding a footnote in someone else’s biography), and it reminds me that I should index the Nelson collection that contains Warlock’s unison choral song.

This handwritten note from March 1929 was written less than two years before Warlock died on 17 December 1930, aged only 36. He is thought to have committed suicide over a perceived loss of his creativity. I believe he was something of a tortured soul, though I’m not familiar with his detailed biography.

I so very nearly didn’t find this note! Yet again, that maxim has proved true. Dogged persistence wins every time. The tragedy is that Warlock (Peter Heseltine) was too tormented to be able to keep going at all. What else might he have achieved? How much more might he have written?

I’m giving a paper at a forthcoming conference at the University of Surrey: Actors, Singers and Celebrity Cultures across the Centuries.

It takes place from tomorrow, Thursday 12 to Saturday 14 June 2025, and is organised under the aegis of the University’s Theatrical Voice Research Centre.

My talk’s entitled, ‘Comparing the Career Trajectories of Two Scottish Singers: Flora Woodman and Robert Wilson‘.

I could write plenty about their concert attire alone (think lace, diamonds and fluted frocks, or smart kilts and jackets) – but obviously, I can only just brush past that particular clothes rail, considering the more significant observations that I’m also making.

Today, I’d like to share some audio that won’t be making it into my talk. Let’s call it ‘extra content’. I’ve recorded some of the Boosey-published ballads that Flora performed at their Royal Albert Hall concerts. Since I’m not a trained singer, I’ve done my best to convey an impression solely on the piano. (I’m not going to start singing here!) I also highlight some of the themes in these songs – captured hearts, broken hearts, the joys of spring and of youth. It’s surprising what you find, if you really look.

Here goes:-

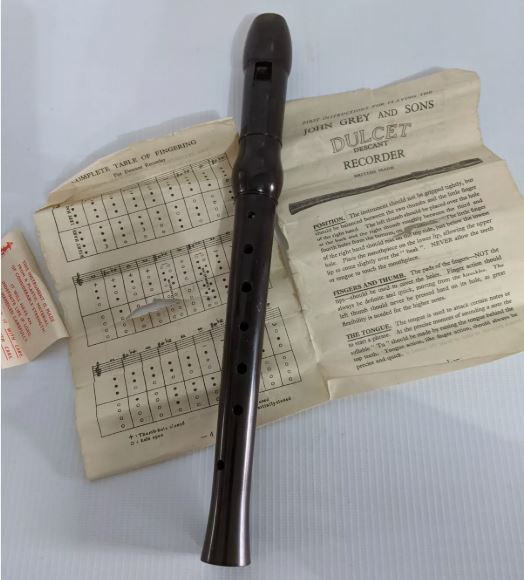

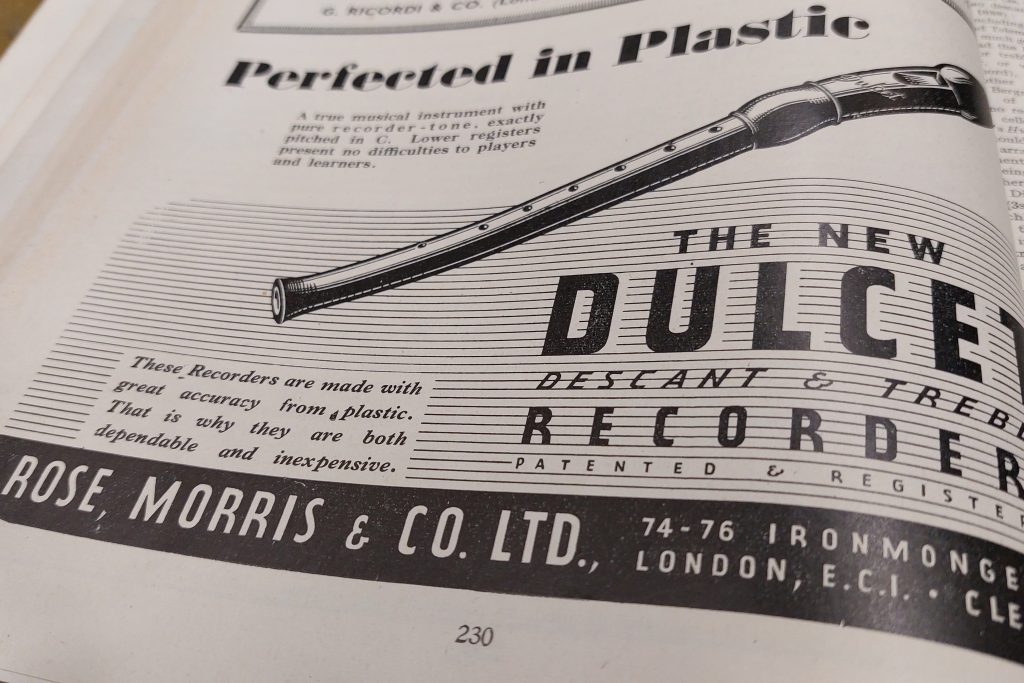

They wondered where I was in the Uni Library this morning – I was off looking at old magazines in the National Library of Scotland!

I did find a couple of book reviews and an advert, which is what I was looking for. But I was also drawn to other adverts for long-playing records, tape recorders and plastic recorders! Here we are today, with our phones, mics, streaming services and laptops, whilst a wooden recorder is much more eco-friendly, not to mention authentic. But in post-war Britain, all this shiny new stuff was the last word in modernity!

As for a record that held four times as much music as a 78? Who wouldn’t want such an innovation?!

Oh, and I spotted another ‘innovation’: folk songs with guitar chords. The times they certainly were a-changing. (And this was a decade before Bob Dylan’s song!)

Anyway, I filled in a couple of gaps in my knowledge by ploughing through eight years‘ worth of bound, unindexed magazines (we forget how amazing digitised journals are!), and answered another question with a microfilmed reel (urgh, old technology!) of another journal. To think that microfilms were comparatively modern when I was a postgrad the first time round. Today, I used a shiny new microfilm reader – very techie – but it’s still a linear way of storing data. Luckily, I found what I was looking for towards the end of the first reel.

And had a thoroughly modern iced latte before heading back to the Uni Library!

Here’s a little curiosity that I came across last autumn. It’s published by Thomas Nelson, yes, but I’m not entirely sure why I bought it. I certainly didn’t know what I was getting!

The title should have given me a clue, but it wasn’t enough to tell the whole story:-

A RURAL SIGHT READER

Being an Amalgamation of “Eyes Right!”

and “Look Ahead!”

Okay, you might say, so there were clearly two earlier books. Correct, there were. But the amalgamation was performed by having “Eyes Right!” (the simpler sight-reading book) on all the left-hand pages, and “Look Ahead!” on all the right-hand pages, until just past halfway through the book. The rest is all ‘Look Ahead” material.

You might ask why? The answer is quite simple. A teacher in a small rural school in those days might have a wide age-range in one class, so they could hand out one set of books (are you with me?) and have two age-groups use it at the same time. The idea was that the older children would follow along when the young ones were sight-reading, and vice versa.

The one thing they could not do, was sing together simultaneously. That absolutely would not work. (Opposite pages might have different time signatures, and or different keys – they were completely unrelated.) Ah well, it was a nice idea. The publishers went on printing it from 1937 until 1948, when His Majesty’s Inspector for Music pleaded with them to reprint it, suggesting that a different title might make it more saleable. There was still a need for it, he insisted. (I have since discovered that he was the unnamed author of this miserable little book!)

It was not reprinted. The publisher’s sales reps reported adverse comments and little customer interest. Looking inside, I’m not surprised. Apart from the first page of ‘Look Ahead’, which patriotically contains the National Anthem with the right rhythm followed by various odd permutations, they aren’t even recogniseable tunes, just abstract little melodies to familiarise the pupils with the ups-and-downs and simple rhythms of notated music. Functional to a fault.

And my copy – look closely at the image at the top – was a publishers’ sample copy. It may never even have been used. But the little singing child image was used again on the front and title pages of two other titles – E Fosbrooke Allen’s A First Song Book, and a much more popular book – Desmond MacMahon’s New National and Folk Song Book vols. 1 and 2. (Possibly elsewhere too – I haven’t seen enough titles to be able to say.)

Whilst I admire the laudable desire to have every child leaving school musically as well as functionally literate, the Rural Sight-Reader is a truly dull and uninspiring little offering. I imagine the children wriggling and kicking under the desk until it was playtime, or time for something more appealing!