‘You’ll be home for lunch’, He said. It was halfway between a query and a command. ‘You have four hours …’ (Actually, that came down to three, once I got to the library. Two, allowing for a coffee and my return journey … )

The Authoress

Nonetheless, I held in my hands the two very poetry books that the author (‘authoress’, in those days) had donated to the city library service back in 1881, not that long after they moved from Lanark to Glasgow. I’ll never know if she handed them in personally, but I think it’s reasonable to assume that she handled those copies at some point.

I can’t show you them. (I signed a library form, which said that I couldn’t share my photos on the internet.) But you can picture two small volumes, one dark green and one purple, a little over six inches tall, with gold-edged leaves, and a little gold-embossed lyre on the front cover of each. Slightly different in design, but very similar.

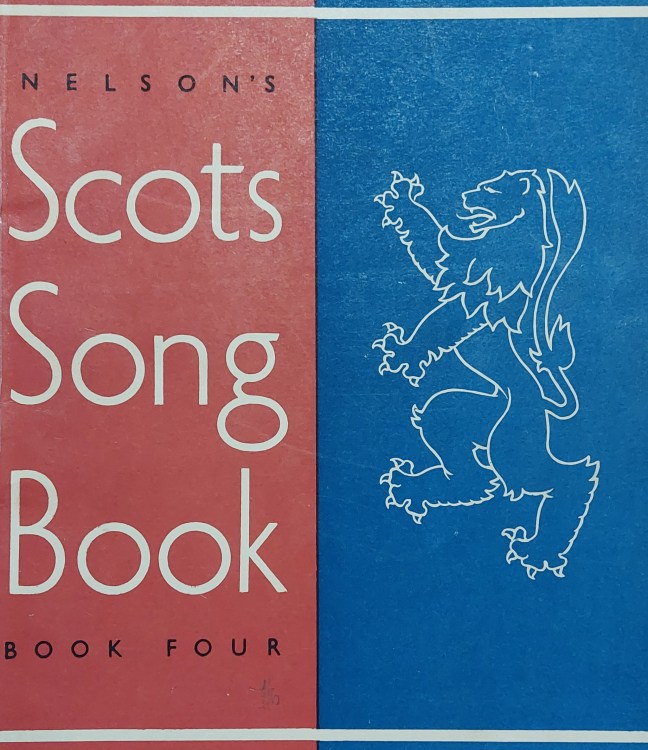

These books are by the mother of one of the women I wrote about in my recent RMA Research Chronicle article.* Only one has been digitized, but I wanted to see them both. I was enchanted to find she had written a poem about ‘my’ heroine, Rose, when Rose was just a small child. It was worth the trip for that in itself. Not that it really added any hard facts to her biography, but still a lovely thing to find.

Anyway, there we were. Me, Mary Ann’s books, and a poem about wee Rose (amongst lots more poetry – I’m not writing here about everything I found!) – so yes, I think I can safely say I came as close as is possible to ‘meeting’ Mary Ann today. But as I said, you’ll just have to take my word for it.

I handed the books back – it was a bit of a wrench, but hey, that’s what happens in a library – and the curtains of time softly closed behind me, leaving Mary Ann in 1881, and myself here in 2026. I may be back – she and I could have more to talk about!

Book Image by Ruslan Sikunov from Pixabay

Clock Image by StockSnap from Pixabay

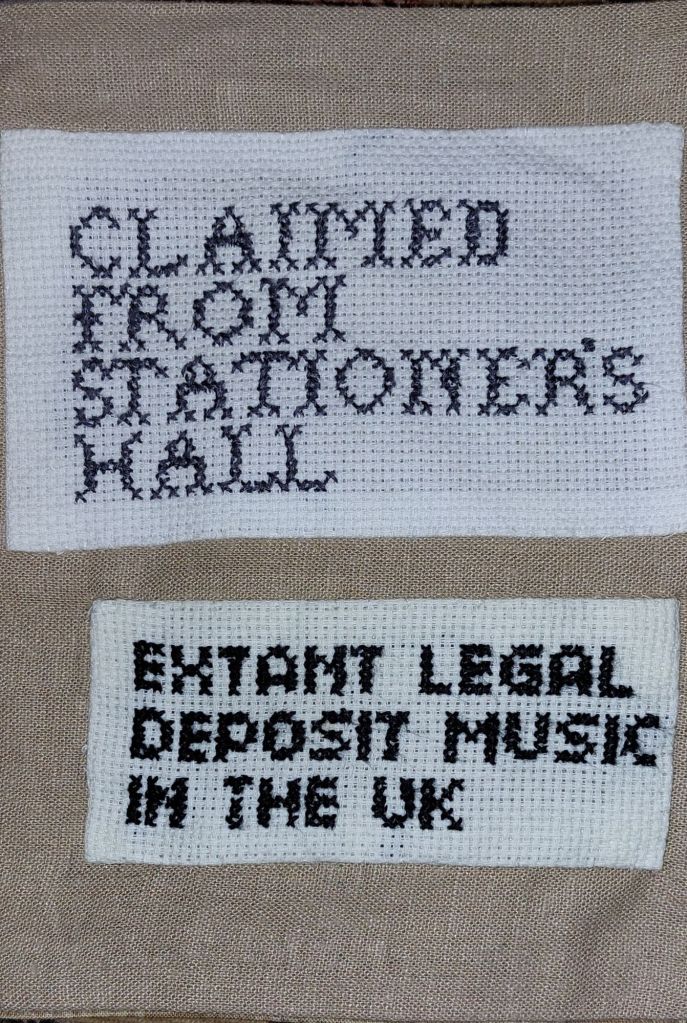

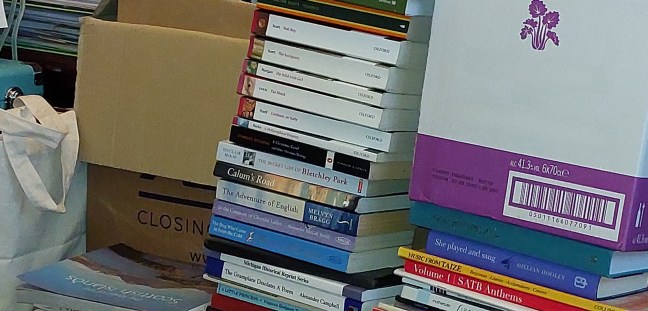

* Article, ‘Women Pursuing Musical Careers: Finding Opportunities in Late 19th- and Early 20th-Century Scottish Music Publishing Circles’, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle , Volume 56, April 2025 [this date is correct], pp. 97 – 118