(Libraries, Lives and Legacies Festival of Research), University of Stirling, 17-18 April 2023

I wrote a report for the conference that I attended in April this year, thanks to an LIHG Bursary. This report has just been published in the latest LIHG Newsletter for Summer 2023 , Series 3, no. 53 (ISSN 1744-3180), pp.7-10.

I thought I’d share excerpts of the report here, too.

The conference resonated strongly with the research topic of my 2017-18 AHRC Networking Grant, Claimed from Stationers’ Hall, when we were investigating surviving music in the British Legal Deposit libraries of the Georgian era. Although my network was interested in books rather than music, I had immersed myself in the Georgian borrowing records of St Andrews University Library, and had taken a particular interest in the music borrowing habits of women of that era, so the opportunity to hear more about what people borrowed apart from music was irresistible.

On the subject of borrowing records, the opening introduction to the ‘Books and Borrowing 1750-1830 project’ and demonstration of the digital resource by Katie Halsey, Matthew Sangster, Kit Baston, and Maxine Branagh-Miscampbell was fascinating, offering so much data for investigation.

The following panel on Reading Practices in Non-Institutional Spaces was just as interesting, with Tim Pye’s ‘Had, Lent; Returned: Borrowing from the Country House Library’, along with Abigail Williams speaking about non-elite book use in rural settings, and Melanie Bigold’s paper about women’s book legacies. Whilst my own interest has been in formal library borrowing, ‘my’ borrowers took music away for their leisure-time enjoyment, and these papers served as a reminder that musicians were probably just as likely to have borrowed music outwith the more regulated library environment. Similarly, the concept of the Sammelband is very familiar to me – that was how libraries kept their legal deposit music. Sam Bailey invented a useful new verb, ‘Sammelbanding’, during the course of their talk on ‘The Reading and Circulation of Erotic Books in Coffee House Libraries’ – a topic far removed from my own research.

Kelsey Jackson Williams’ hands-on session with books from the Leighton Library, in an exhibition curated by Jacqueline Kennard, was the perfect after-lunch session, offering the chance both to stretch one’s legs on the way there, and to inspect some rare selections from the Leighton.

Parallel sessions meant tough choices, but I opted to hear Angela Esterhammer talk about John Galt’s various publishing ventures – an intriguing history – followed by Cleo O’Callaghan Yeoman’s ‘Still my ardent sensibility led me back to novels’. (I reflected that St Andrews’ first music cataloguer, Miss Elizabeth Lambert, had read a wide variety of books, and whilst her reading included travel accounts, religious books, and books on botany and conchology, she certainly wasn’t averse to reading a good novel, too.) Next came Amy Solomon talking about Anne Lister’s considerable book collection at Shibden Hall, and how she had made an inherited collection her own, as well as keeping commonplace books, diaries, and reading journals. I regret having missed seeing the films about her diaries, and the two more recent ‘Gentleman Jack’ series on the television.

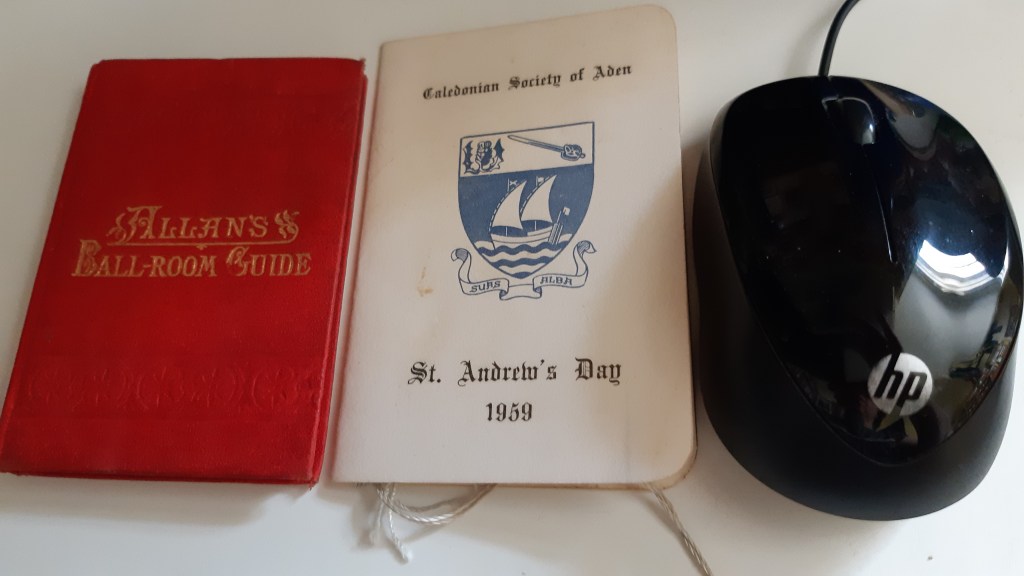

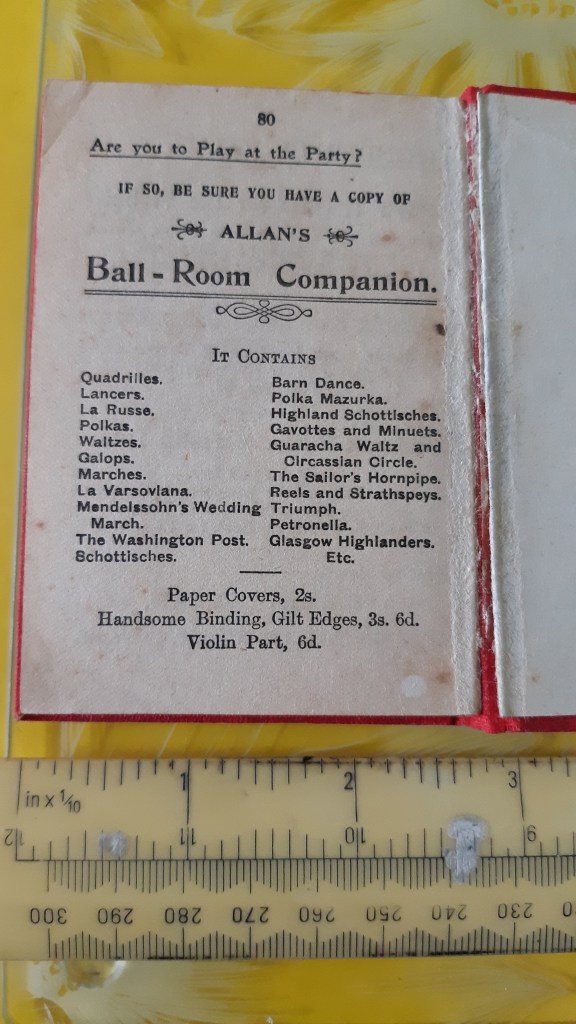

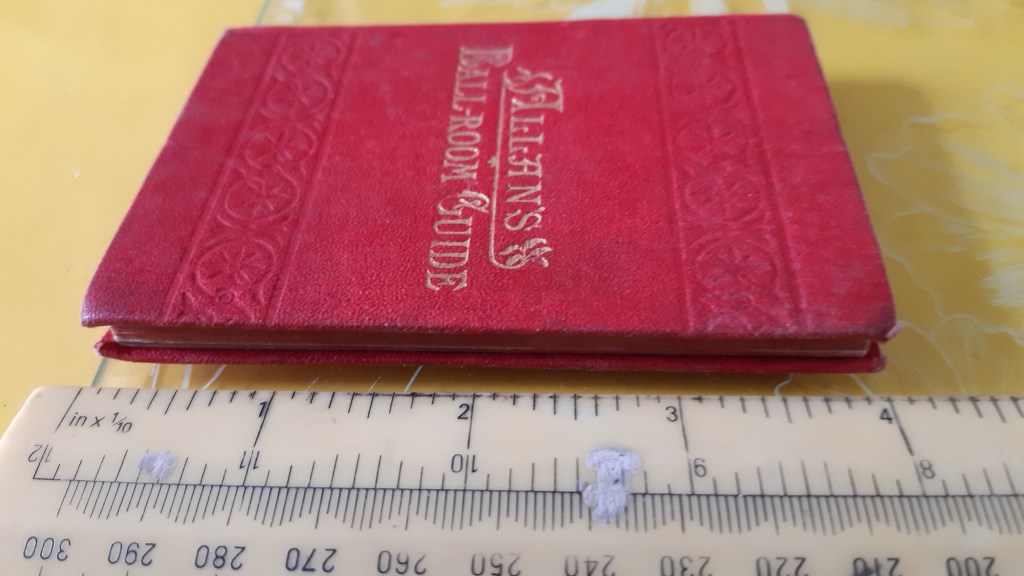

The first keynote paper was given by Deidre Lynch, on ‘The Social Lives of Scraps: Shearing, Sharing, Scavenging, Gleaning’. I am sure I was not the only delegate pondering as to whether any of my own ‘scraps’ would survive to intrigue future readers, but more importantly, Deidre’s paper reminded us that proper ‘books’ are only a small proportion of the vast amount of printed material still surviving, often against the odds and far from their original context.

On the second day, the opening plenary roundtable chaired by Jill Dye addressed borrowers’ records across Scotland, and I heard from several people with whom I was already acquainted, three of them through my own AHRC Networking project.

We heard about the library of Innerpeffray, the National Library of Scotland, and Edinburgh, Glasgow and St Andrews’ University Libraries. I was interested to hear about the bigger picture, so that I could place my own special interests into the wider context.

For the third panel, I opted for the panel on Readers, Libraries and Loss. Jessica Purdy gave a fascinating talk on ‘Libraries of Lost Books?’, speaking about chained church libraries, and the fact that their tight security and still pristine condition suggest that the books might as well have been ‘lost’ as far as most of the local residents were concerned. Elise Watson, too, made us reflect upon just how many publications of Catholic devotional material had been published, even if they were so ephemeral that there are now ‘”Black Holes” of Ephemeral Catholic Print.’

For the fourth panel, I attended the panel on ‘Education’, hearing Maxine Branagh-Miscampbell talking about the Grindlay bequest and ‘Childhood Reading Practices at the Royal High School, Edinburgh’. The Grindlay bequest was valued sufficiently that it was all added to stock, even though some material was never going to interest young or teenage boys. Mary Fairclough gave an interesting talk on ‘Barbauld’s An Address to the Deity and Reading Aloud’. I have recently encountered Victorian publishers appropriating evangelical hymns for magic lantern shows, but had not considered that poetry might also be ‘trimmed down’ and repurposed.

Duncan Frost’s paper did have a musical subject: ‘Bird Books: Advertising, Consumption and Readers of Songbird Training Manuals’. Who would have thought that so many books were written about catching and training songbirds to sing in captivity?! The most intriguing aspect of this genre of books was in fact that, despite many pages dedicated to all aspects of caring for and training your bird, there was significantly little information about the kind of tunes that you might want to teach it.

The second and closing keynote lecture was delivered by Andrew Pettegree, on ‘The Universal Short Title Catalogue: Big Data and its Perils’. Professor Pettegree was at pains to underline not only what the USTC had achieved, but also its shortcomings, or rather, what it was not. We were also reminded of some aspects that I have encountered in my own work: that books in libraries were not the only copies of these titles; they would have existed plentifully outside libraries, and so might other books which we can now only trace by, for example, publisher’s catalogues and advertisements. Moreover, library catalogues can conceal different editions, or show duplicate entries, depending on minor differences in cataloguing approaches.

Since my own networking grant, I have had to reflect upon the benefits of the work, and the impact the research has had. One of the outcomes that I identified then, was that library history research created effectively a ‘third space’ where librarians and academic scholars – and those like myself, straddling both library and research worlds – could meet and beneficially share our insights and learning. I realise that at this recent conference I had experienced exactly the same kind of meeting of minds again. Similarities of approach and a common interest in library and book history meant that I felt I had an underlying understanding enabling me to benefit from their fresh insights.

I am grateful to the Library and Information History Group for enabling me to attend this wonderful and thought-provoking conference. Besides having such a rich array of papers to listen to, I certainly did benefit from the opportunities to talk to other delegates. It was a treat to be able to take two days out of normal routine in such a beautiful setting, giving plenty of food for thought for the future.

Image: Image by G.C. from Pixabay