Attribution and Authorship

When I’m talking to students about oral transmission of folk songs, my take is – perhaps a bit controversially – that I believe a lot of songs were actually written by ONE person. Passed on, passed around, changed certainly, but I don’t buy the idea that they somehow ‘grew’ anonymously or collectively out of the soil. Maybe a group of pals did sometimes sit in the pub, stand in the fields or sit at their looms working up words or a tune, but as often as not, someone ‘wrote’ or devised that song. We just don’t always know who did.

Tune Variants

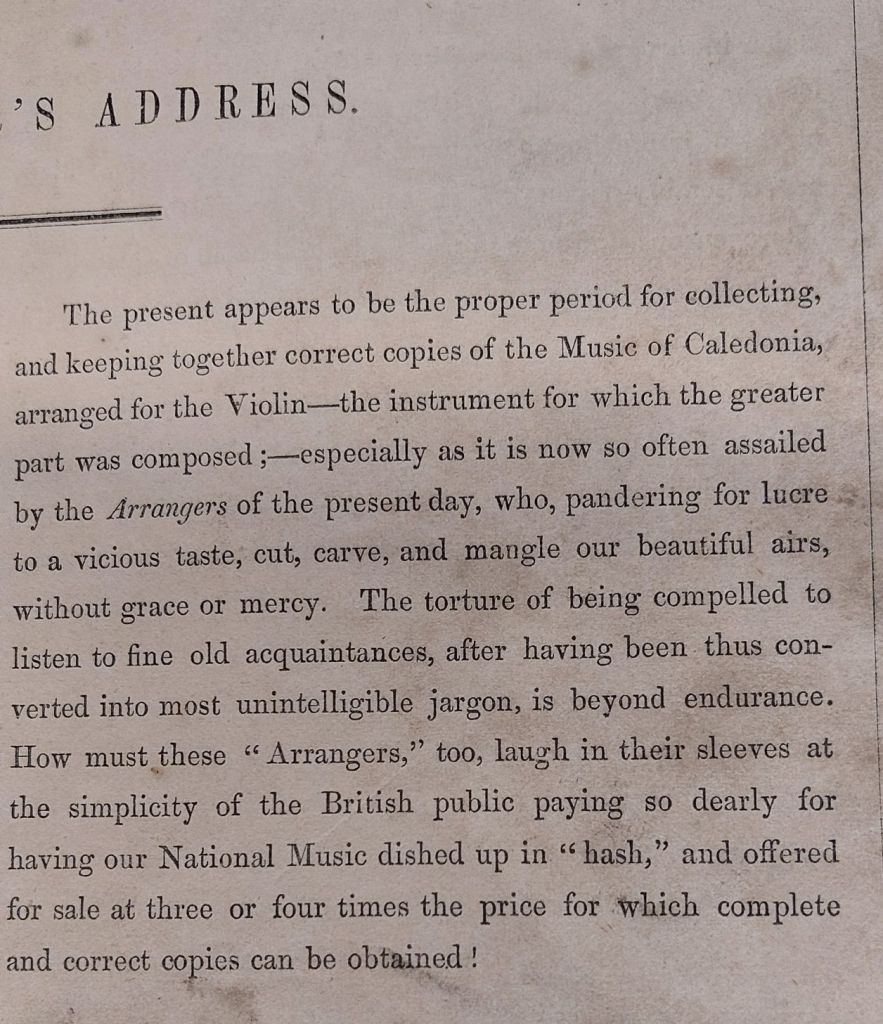

The other problem, of course, is variants. If you pass things round and they get picked up by ear, or someone writes it down – but not exactly how it was performed by the last person – the tunes change slightly. Or, in times-gone-by, gaps between crotchets got filled in by two stepwise quavers, or an ornament got written out in full. And how do you determine what the ‘right’ version is? I don’t think you can, often enough, though you can certainly try to identify the most common form of a tune. Or if you’re able to, the earliest printed version. (If Hamish McHamish wrote a song in 1825, then the earliest printed version is most likely to be closest to his intentions. But unless he took his tune to the printer, or published it himself, you can’t be sure. )

The Ravages of Time

So we have at least a couple of centuries in which some tunes had the opportunity to change a multitude of times. (And that’s before an accompanist decided that G7 would be better than E minor at a particular point …) Try and compare a song in three different published collections. It won’t necessarily be exactly the same.

The Strong but Wrong Singer

I also use the modern-day example of my own church organist experience. You teach the congregation a new tune. A strong singer gets something wrong, and thereafter, try as you may, everyone sings Jemima’s version of the tune. That, too, could be construed as oral transmission in action!

(And as for Technology)

Today, we had a new song. The choir had studiously learned it, syncopated rhythms and all. We sang it first as an anthem. Later, we sang it with the congregation. Even the syncopations went moderately well, though I can’t say I was listening out for those who, ‘like sheep had gone astray’ (to quote Handel’s Messiah). There was only one problem: the verses appeared on the PowerPoint in the wrong order, and there was not a thing could be done about it once we’d started. When the choir sang it with the congregation, the latter sang what they could, or what they saw on the screen …. ! Maybe that’s why the syncopations went well – not everyone was actually singing.

All I can do is offer a corrected version of the lyrics for the PowerPoint, and we’ll try again another day. Who knows what might have changed in the meantime?

Of course, it’s a highly competitive world out there. I can’t attempt to rate my chances. But I rewarded myself for getting it written and submitted on time, by ordering a wee Victorian Glaswegian souvenir jug. And we’ll see what unfolds!

Of course, it’s a highly competitive world out there. I can’t attempt to rate my chances. But I rewarded myself for getting it written and submitted on time, by ordering a wee Victorian Glaswegian souvenir jug. And we’ll see what unfolds!