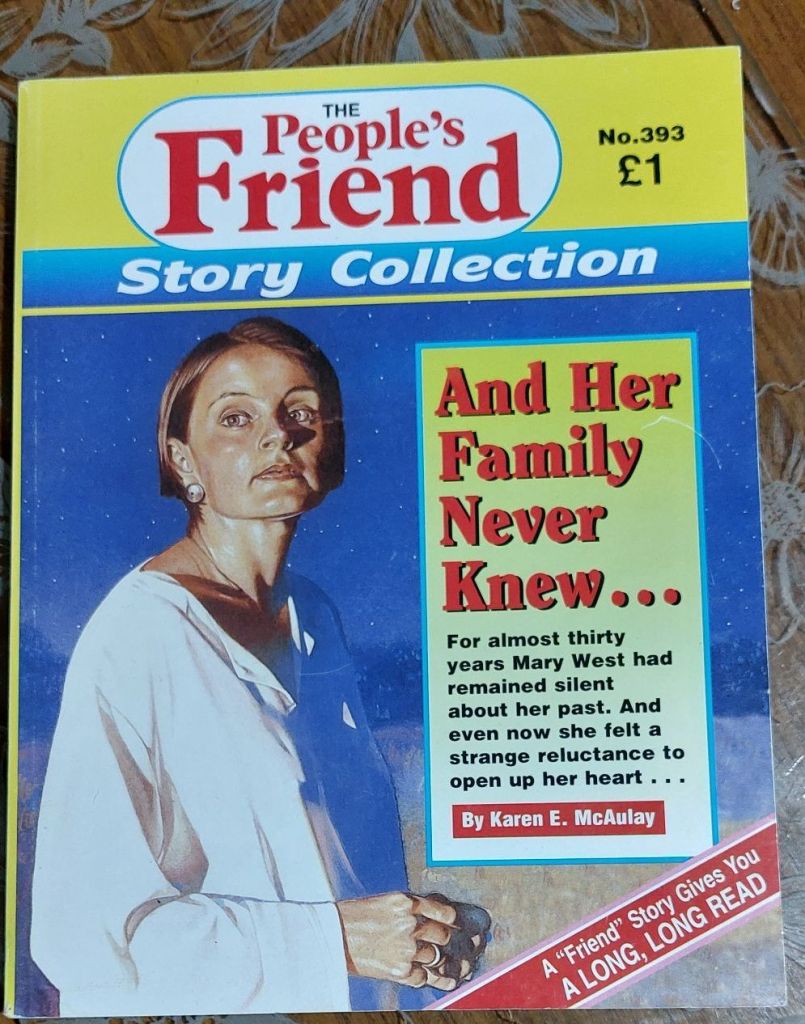

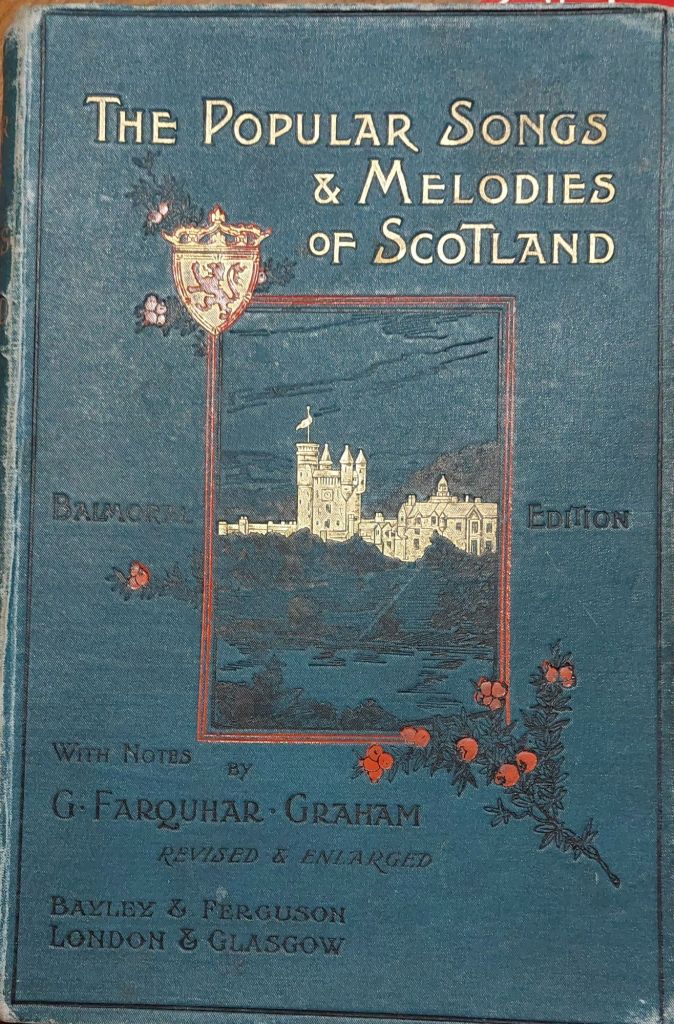

It stands to reason. If I’m researching the John Leng Scots Song competitions, then I might also be interested in this firm’s publications. Not, of course, that there’s any direct link between Leng’s trust fund and the firm’s later publications. They published general material, magazines and newspapers, and only a handful of music titles. However, this means that what music they did publish would be of a kind suited to the mass market.

Is it any surprise that, amongst the ‘Aunt Kate’s’ housekeeping and embroidery books, there might also be dance music and national songs? Which of course indicates their recognition of how popular national songs actually were.

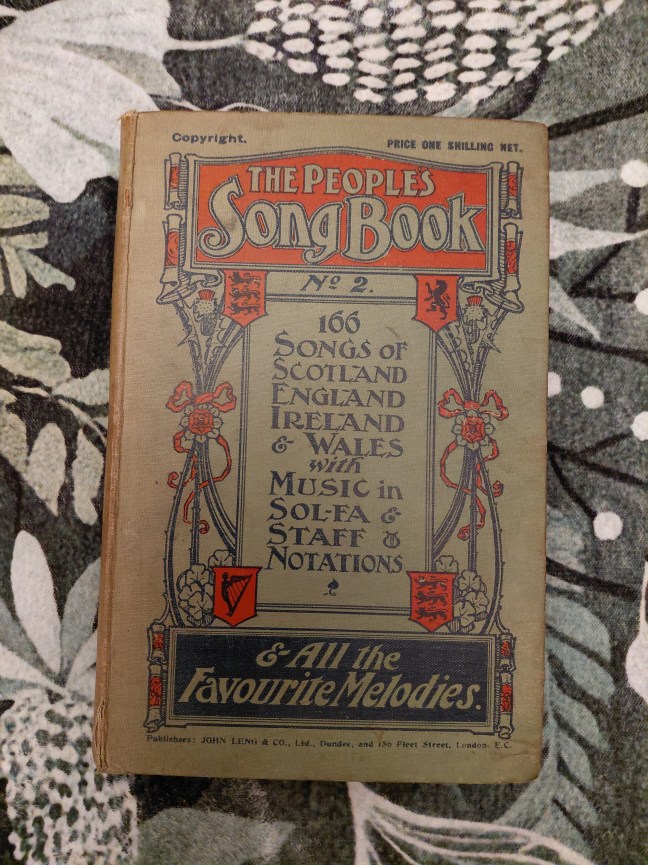

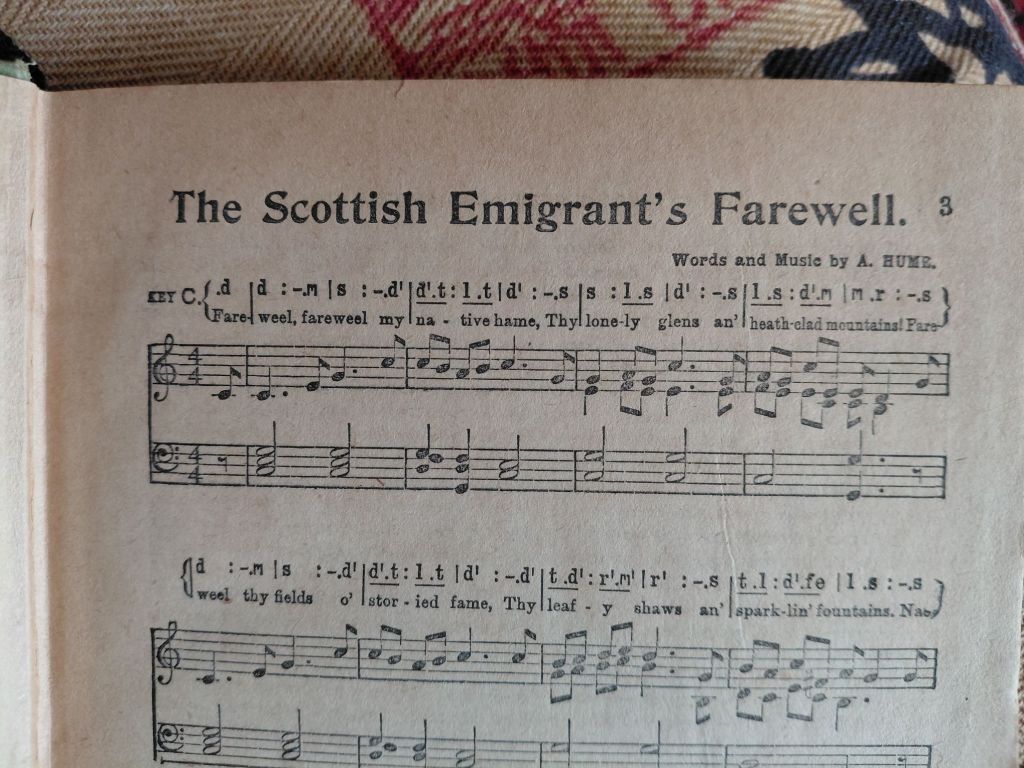

This week, I bought the second volume of The People’s Song Book, published in 1915. It’s quite an attractive little book, containing 32 Scottish, 33 English, 35 Irish and 34 Welsh songs.

There’s also a section with 32 of the now distasteful genre of ‘minstrel’ songs at the back – blackface minstrelsy, not the homegrown wandering minstrel variety. They are described more insultingly than that, as was the unfortunate custom of that era.

Curiously, these are indicated as a third series of English songs, lower down the page. (The second series appeared after the Scottish songs. Remember, this was the second book, so the ‘first series’ of English songs is presumably there.)

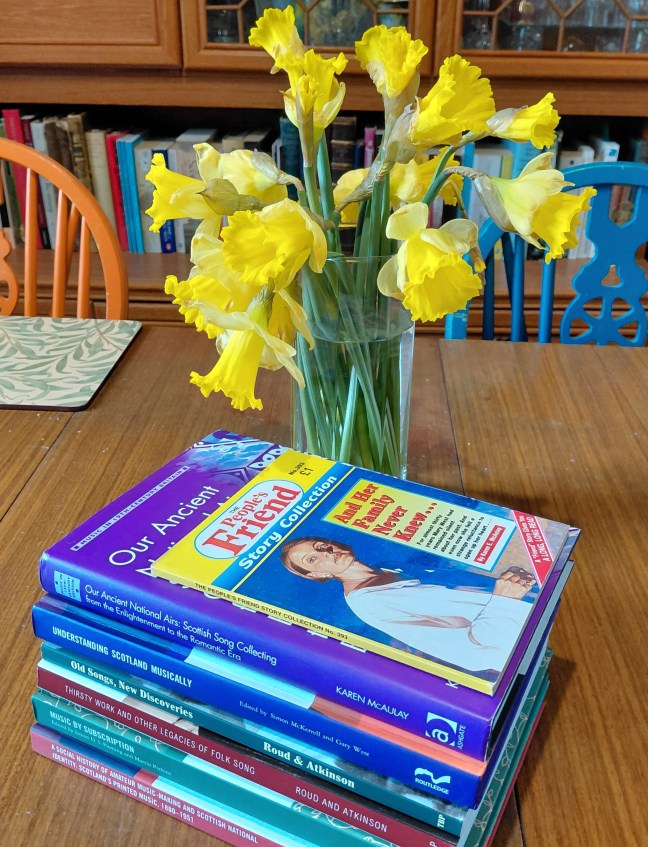

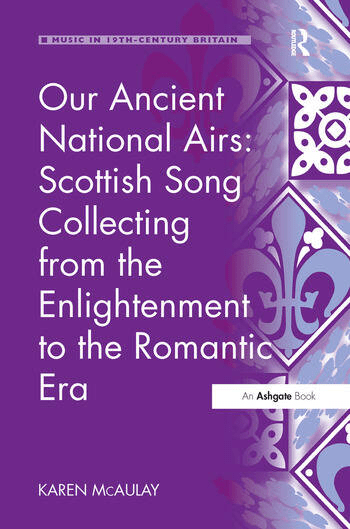

Today, we recognise the English and American origins of the minstrelsy repertoire, but I doubt the compilers were hinting at that. I have written at some length about such songs in my recent monograph – what’s in the present book is no different to those in the collections I’ve already examined.

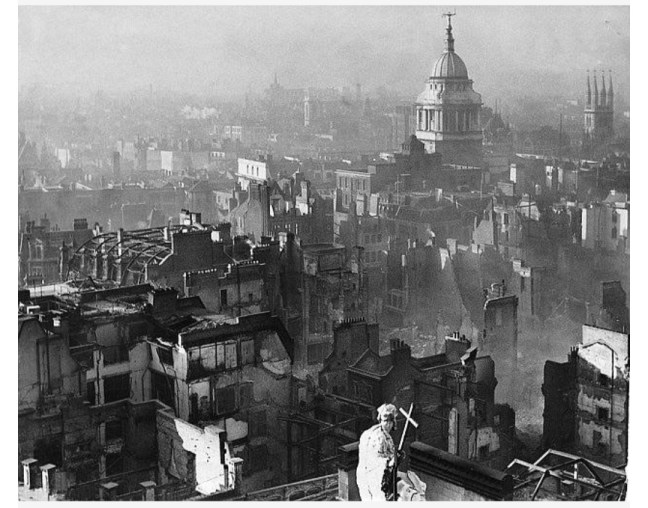

Notwithstanding this – because we have to recognise that the book is a product of its age, whatever our more informed modern opinion – it would be a strange scholar that acquired book 2, but wasn’t curious about book 1, so I’m excited now to be repatriating the first volume from Virginia. Perhaps some expat took it with them in their trunk, or had it sent to them as a keepsake? And now it’s coming home – it feels appropriate.

The funny thing about Virginia – on a completely unrelated note – is that, a quarter of a century ago, I attended a librarianship interview in Richmond. I didn’t succeed – but I did start my doctoral studies at home in Glasgow, a year or two later. None of what I’ve subsequently done, would have been done at all, if I’d become yet another emigrant like those of a century before.

And now a little national song book is making its way home to me. I’ll be sure to make it welcome!

And More?

Book 1 may answer an intriguing question that arose yesterday. I’m impatient!