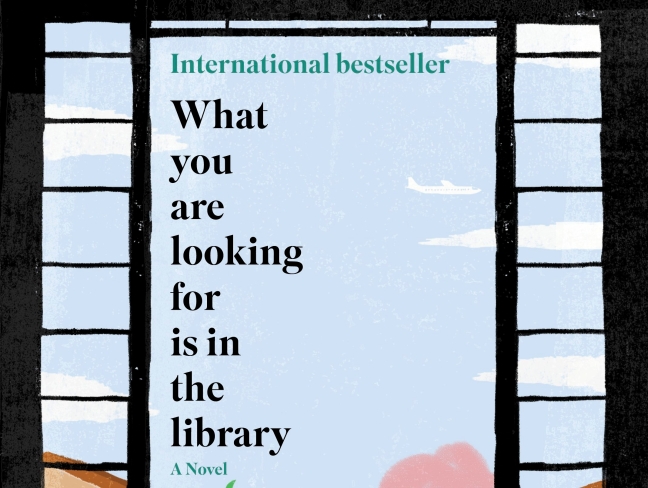

I accepted a generous donation of old books to the Library a couple of weeks ago. This presented me, personally, with a bit of a problem because our offices, furniture and contents are being moved around, and I had proudly emptied most of my shelves in readiness. There will be fewer shelves in the other office. And now I had two shelves full of old Scottish music – right up my street – which needed cataloguing.

- Most vital priority – get them done before I retire from the Library.

- Almost as vital – to get them done before the move on Thursday next week!

Of course, the lovely thing is that they’re books I’ve encountered in various research contexts … the PhD; the Bass Culture project (https://HMS.Scot); the book chapter on subscriptions; and my own forthcoming monograph.

I catalogued like crazy on Thursday and Friday. I’ve catalogued Sammelbande (personal bound volumes) of songs, piano music and fiddle tunes. I’ve shown colleagues books signed by George Thomson. I’ve indexed Gow’s strathspeys and reels. And yesterday I blogged about James Davie and his Caledonian Repository.

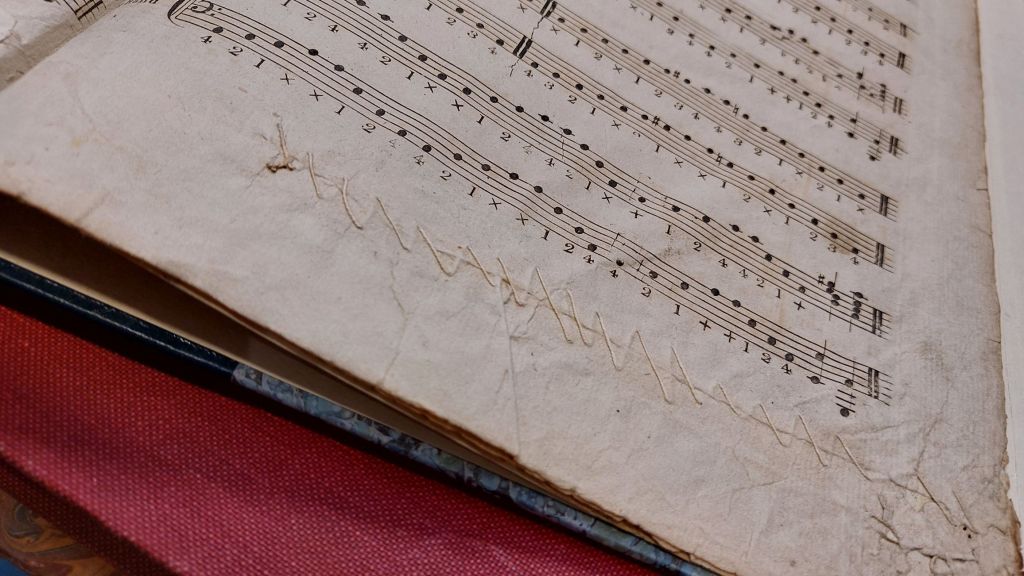

But I’ve also just enjoyed handling the music, because sometimes one finds some endearingly human evidence of the scores being used, even to the point of needing mending. It’s quite touching to ponder how much a piece had been used, before it actually needed stitching – here, along a line where the edge of the printer’s block had originally left a dent in the paper:-

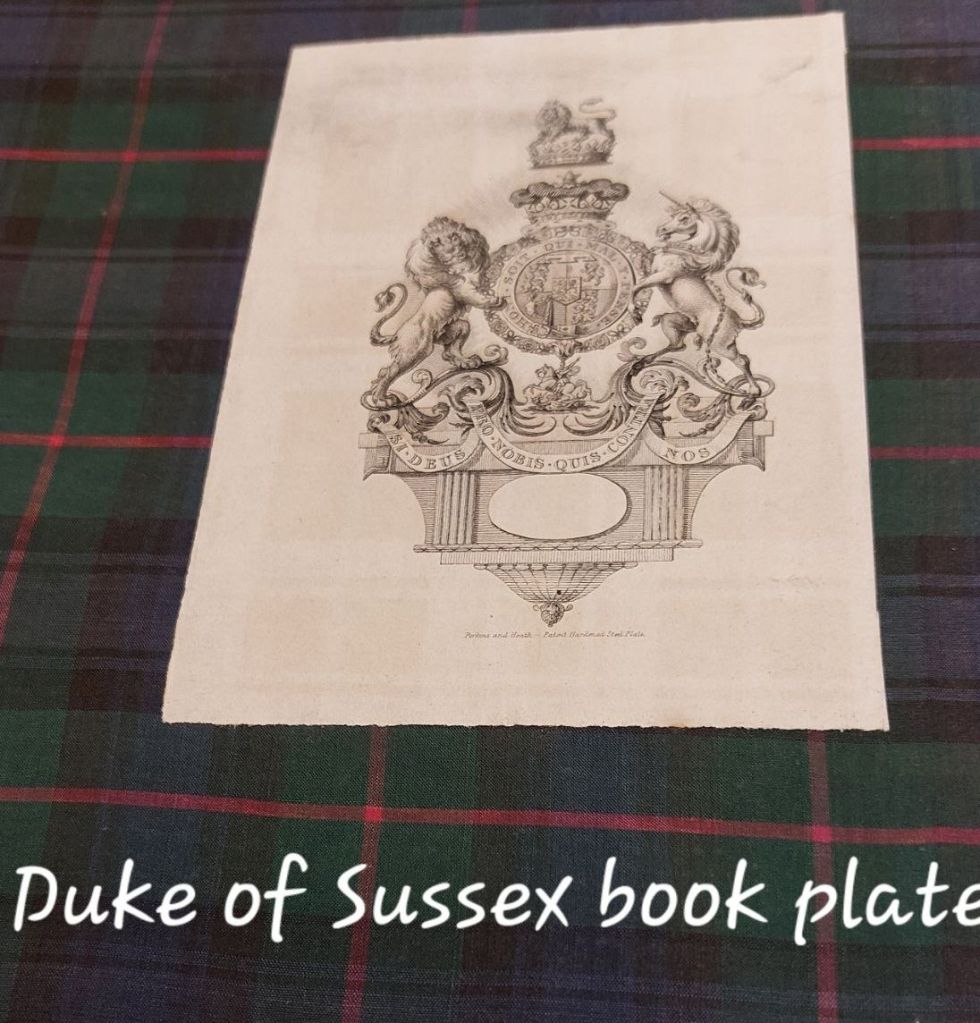

I’ve smiled at Georgian ladies’ stitched repairs to much-loved pieces, noticed with amusement a handful of early Mozart Allan books (yes, including some strathspeys and reels) in a fin-de-siecle Sammelband which had seen better days; spotted piano fingerings pencilled in; and best of all, found a tartan ribbon in a volume dedicated to the Duke of Sussex – his personal copy, which was first sold out of the family’s possession in 1844. His library was dispersed after he died in straitened financial circumstances:-

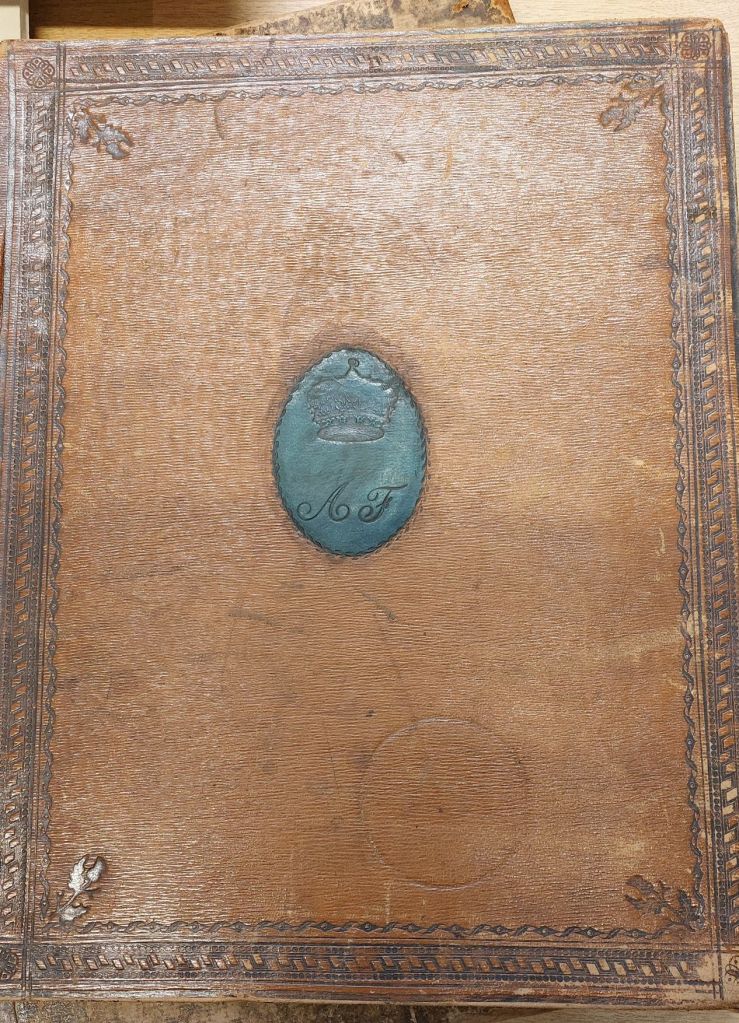

Nine Scots Songs and three Duetts, newly arranged with a harp or piano forte accompaniment / by P. Anthony Corri

Whittaker Library catalogue entry

This book has the Duke’s family crest on a label pasted inside, and the outer cover is embossed with ‘A F’ (Augustus Frederick), reflecting the monogram on the title page.

The tartan endpapers and tartan ribbon between pp.30-31 are a perfect illustration of what I have written about in a chapter on tartanry in my forthcoming monograph. Everyone – whether nobility or commoner – liked a bit of tartan on or inside their Scottish song books, and here, someone even found a bit of tartan ribbon to use as a bookmark.

I have just a few of those books left to catalogue now. There’s an intriguing one without a cover or title page, waiting for 9 am on Monday …! Hopefully, I’ll end up with an empty bookcase again.