Burns Night is on Sunday 25 January 2026

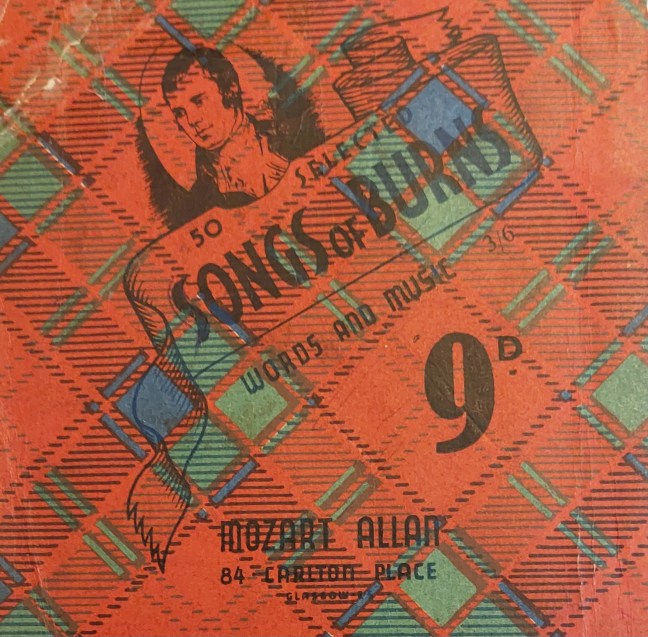

This Saturday, 24 January, is virtually Burns’ Night, so what better afternoon to have A Celebration of Burns at the Central Library of Dundee? I understand we were fully booked, but those lucky enough to have obtained a ticket had a great afternoon. Click on the link (as long as it’s still there) to see the line-up.

And I finished up the event with a singalong of three favourite songs by Robert Burns – not bad for a girl from Norfolk! If I play, and everyone else sings, my English accent is well-concealed …

But what are the three songs?

Green Grow the Rashes, O.

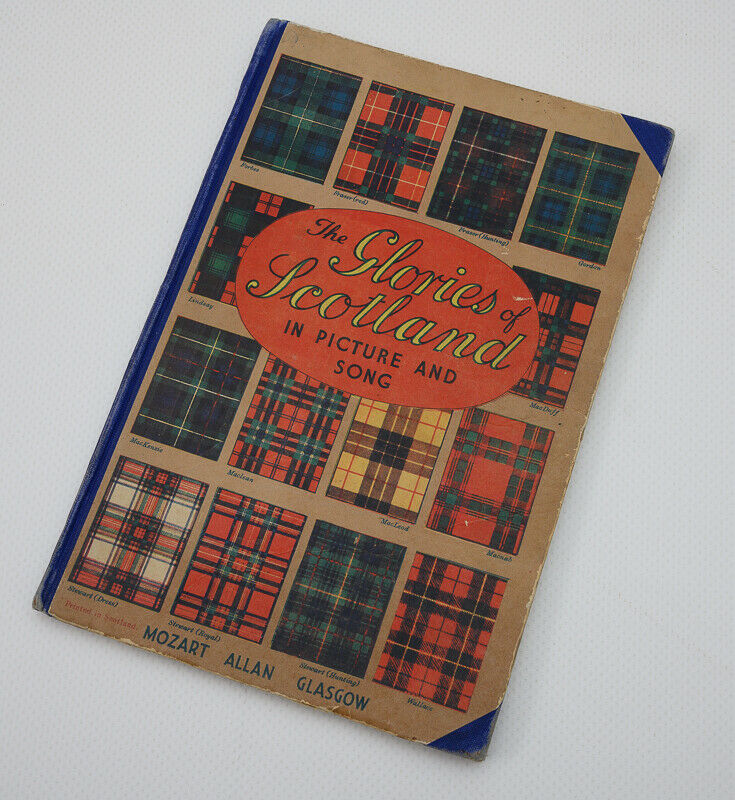

Burns’ version of this pre-existing song appeared in the Scots Musical Museum song collection in the late 18th century. It was included in several school song books in the 20th century, and remains popular to this day.

CHORUS: Green grow the rashes, O; Green grow the rashes, O;

The sweetest hours that e’er I spend, Are spent amang the lasses, O.

1. There’s nought but care on ev’ry han’, In ev’ry hour that passes, O:

What signifies the life o’ man, An’ ’twere na for the lasses, O.

Green …

2. The war’ly race may riches chase, – An’ riches still may fly them, O;

An’ tho’ at last they catch them fast, Their hearts can ne’er enjoy them, O.

Green …

3. Gie me a cannie hour at e’en, My arms about my dearie, O;

An’ war’ly cares, an’ war’ly men, May a’ gae tapsalteerie, O!

Green …

4. For you sae douce, ye sneer at this; Ye’re nought but senseless asses, O:

The wisest man the warl’ e’er saw, He dearly lov’d the lasses, O.

Green …

5. Auld Nature swears, the lovely dears Her noblest work she classes, O:

Her prentice han’ she try’d on man, An’ then she made the lasses, O.

Green …

Comin’ Thro’ the Rye

There was a very famous soprano called Flora Woodman (1896-1981), who was born in London of Scottish parents. For some years, this was practically her signature tune – she sang it a couple of hundred times.

But why? I discovered that there had been a novel called Comin’ thro’ the Rye, written by novelist Helen Mather back in 1875. The heroine sings this song as she walks through a rye-field; that’s the only connection with the song.

But the story became a silent movie in autumn 1916 – months after Flora started singing it. The film was so popular that the film producer remade it in 1923. Flora was still singing the song – probably because the film had popularised it – but the film went out of fashion when the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, came out in 1927, and Flora began to sing the song less often.

As for the words – the clean words – you won’t be surprised to learn that even this version didn’t make it into any school books of Scottish songs!

Comin’ thro’ the rye

1. Gin a body meet a body Comin’ thro’ the rye, Gin a body kiss a body, Need a body cry?

Chorus: Ilka lassie has her laddie, Nane, they say, hae I, Yet a’ the lads they smile at me, When comin’ thro’ the rye.

2. Gin a body meet a body Comin’ frae the town, Gin a body kiss a body, Need a body frown? Chorus

3. Gin a body meet a body, Comin’ frae the well, Gin a body kiss a body, Need a body tell? Chorus

4. ‘Mang the train there is a swain I dearly lo’e myself, But what his name or whaur his hame, I dinna care to tell. Chorus

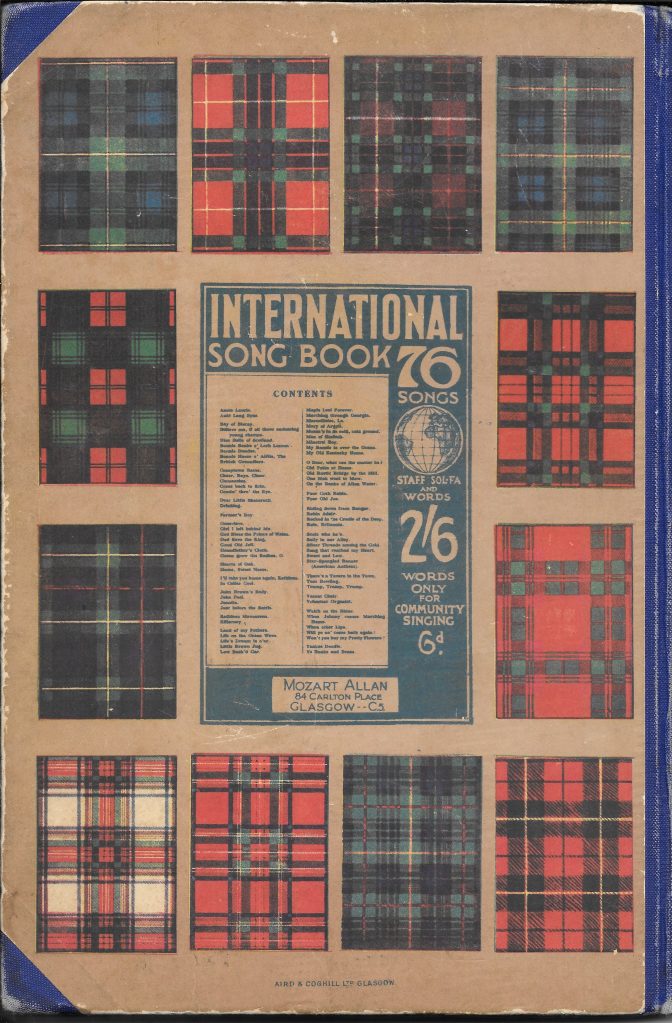

Auld Lang Syne

Our last song needed no introduction!

1. Should auld acquaintance be forgot, And never brought to mind? Should auld acquaintance be forgot, And the days o’ auld lang syne?

Chorus: For auld lang syne, my dear, For auld lang syne, We’ll tak’ a cup o’ kindness yet, For auld lang syne.

2. And here’s a hand, my trusty fiere, And gie’s a hand o’ thine; And we’ll tak’ a right guid willie-waught For the days o’ auld lang syne. Chorus.